Go'ing Insane Part Four: Mandatory Mutation

First off, let’s get the standard caveats out of the way:

- The purpose of these posts is not to denigrate the language: it’s to see who shares my grievances

- These things bother me, they may not bother you. Much of what I take issue with is considered nitpicking and I don’t disagree

- I’m not an authority on Go, I just use it in open-source projects

- On average these posts contain at least one embarrassing error. If you’re reading near the time of publication, you may spot such an error

- Many Gophers value simplicity over richness, some believing simplicity actually affords more expressiveness than richer languages. I disagree but understand

- This series does not attempt to be balanced. There are many good things about Go (fast compile times, compatibility, etc), but there are plenty of other posts talking about those. Do not let this series alone determine your perspective on Go

With that out of the way, let’s begin.

When in Rome we do as the Romans do, and when in Go we do as the Gophers do, which means mutation everywhere.

Mutation in Javascript

At my day job I share John Carmack’s self-identification as as a const-nazi. If I’m reviewing code and see something like this in javascript:

let env = 'dev';

if (isProd) {

env = 'prod';

}

// (env is never assigned to again)

I’ll suggest that we use const instead like so:

const env = isProd ? 'prod' : 'dev';

This is not for the sake of sparing keystrokes or vertical space. It’s because it gives the reader more information to help them understand the code. If you see a const keyword before a variable you can rest assured that that variable will never be re-assigned a value, which saves space in your brain for reasoning about the rest of the code.

Given how often a variable’s value is conditional on something (in this case the value of isProd), it helps when your language provides a conditional control flow construct which is itself an expression, meaning it can be used in the right-hand side of an assignment. This allows you to declare and define a variable once without needing to reassign it afterwards, and that makes a keyword like javascript’s const highly valuable in comunicating the intent of your code. In the absence of such a conditional expression construct, you can still wrap conditionals in functions but doing so can be clunky.

Mutation in Ruby

Ruby lacks a const keyword (you can freeze objects to prevent mutation can’t prevent a variable from being re-assigned to), yet even in ruby I’ll push for minimising mutation. For example, in a world where Ruby lacked the ternary operator, I would still prefer …

# in Ruby, as it is with Rust, if statements and switch statements are themselves expressions,

# meaning they can live on the RHS of an assignment

env = if is_prod

"prod"

else

"dev"

end

… to …

env = nil

if is_prod

env = "prod"

else

env = "dev"

end

… because it reduces the amount of code you need to mentally parse, and reduces the chance of bugs (e.g. some variable other than env may erroneously be on the LHS in one of those assignments).

Mutation in Go

This brings us to Go. Go has a const keyword but it can only be used when the right-hand side of the assignment holds a basic type like an integer or string literal. Go constants can’t be re-assigned and their values can’t be mutated because Go constants can’t hold mutable values. As such I only see a handful of constants in the typical Go package, and rarely on the inside of a function where most of the action happens.

const myConst1 = 1 // okay

const myConst2 = []int{1} // ERROR: ([]int literal) (value of type []int) is not a basic type

myVar := 1

const myConst3 = myVar // ERROR: myVar (variable of type int) is not constant

Even if Go allowed the const keyword (or some similar keyword to mark a variable as immutable) when the RHS contained a variable, it wouldn’t help much with the common requirement of determining a value based on some condition, given Go’s lack of conditional expressions. Yes, you could use a function call on the RHS but I find that to be overkill.

In Go, if I want to set my env variable to "prod" or "dev" depending on isProd I have four choices:

env := "dev"

if isProd {

env = "prod"

}

Or this longer form:

var env string

if isProd {

env = "prod"

} else {

env = "dev"

}

Or using an IIFE (I’m pretty sure nobody does this):

env := func() string {

if isProd {

return "prod"

}

return "dev"

}()

Or using a separately defined function (again, for something this trivial, I’m pretty sure nobody does this, and based on this stack overflow thread, looks like the Go team only endorses doing this when you would need to call the function in multiple places):

func getEnvStr(isProd bool) string {

if isProd {

return "prod"

}

return "dev"

}

...

env := getEnvStr(isProd)

So why does Go lack a ternary operator?

The Ternary Operator

In the Go FAQ, under the question about the absence of ternaries from the language, the if-else approach is advised. Under the example they say

The if-else form, although longer, is unquestionably clearer [than a ternary].

Allow me to question the unquestionable. If you’re somebody who understands the syntax of a ternary, it’s pretty clear.

What if you don’t understand the syntax of a ternary? I’ve heard the argument that the ternary operator is hard to learn and we can’t expect everybody to know it, but this argument doesn’t resonate with me: If you’re a developer learning Go, you’re probably familiar with at least one other language and given that Javascript, Ruby, C, C++, C#, Java, Perl, PHP, Swift, Crystal and Dart, all use ternary operators, what are that odds somebody has never come across the ternary operator before learning Go? I’d say slim. On the off-chance somebody is unfamiliar with the operator, it takes two minutes to learn it: far less time than it takes to understand how Go’s channels work for example. And that’s two minutes they’re going to have to spend sooner or later, unless they manage to avoid all the above-listed languages for the remainder of their life.

In fairness, there are two arguments I hear against ternaries that do resonate with me. The first is that when nested they are hard to read. I completely agree with this argument, as do the linters of pretty much every language I’ve used that has ternaries. I wouldn’t even mind if the Go team allowed ternaries but disallowed nesting them. The second argument is that although adding ternaries (or conditional expressions in general) would not itself raise the complexity waterline much, if a bunch of similar features were added, we could end up in a language that’s needlessly complex, which is antithetical to Go’s desire for simplicity. Can’t argue with that, other than to say I simply don’t value simplicity as much as other Gophers.

At any rate, I find that the debate around ternaries is poorly framed: it should really be a debate around conditional expressions (of which ternaries are an example), and I would happily forgo ternaries to have if-statements and switch statements treated as expressions, but I suspect this too would exceed Go’s complexity budget.

Assuming that we’re dealing with somebody who recognises the ternary operator, let’s rank the following alternatives from most to least clear:

// 1) Most clear: If-statements as expressions

env := if isProd { "prod" } else { "dev" } // not actually valid Go syntax

// 2) Using ternary operator

env := isProd ? "prod" : "dev" // not actually valid Go syntax

// 3) Using mutative if-else statement

var env string

if isProd {

env = "prod"

} else {

env = "dev"

}

// 4) Least clear: using mutative if statement

env := "dev"

if isProd {

env = "prod"

}

Note that options 1 and 2 read the same from left to right: if isProd is true, set to “prod”, otherwise set to “dev”. This is the natural way you would explain the logic in english. Admittedly option 3 also shares the same flow, however it’s spread over six lines and the reader has to work harder to recognise what’s actually going on: Hmm so we assign “prod” to env in the first case and “dev” to env in the other case and oh right so this is basically mimicking a ternary.

Option 4’s flow is backwards. As the reader follows the code they think: So env’s value is “dev”… oh wait no we’ll change that value to “prod” if isProd is true. The oh wait part of that process is exactly what we want to avoid when writing code: we should be minimising surprise whenever possible.

Why am I bothering to evaluate the fourth option, given that the Go team didn’t advise it and it’s the least-clear alternative? Because it’s the option I see the most, likely because it requires the fewest keypresses, but also because many consider it idiomatic. In a world with conditional expressions, lazy developers like me can save themselves keystrokes without sacrificing clarity. But Gophers do not live in that world, so clarity suffers as a result.

From my perspective, Go’s simplicity stands in opposition to expressiveness: I lack the tools required to communicate what a developer can expect as they read my code (e.g. this variable will never be assigned to again) which makes it harder to glean what’s going on as the reader. Better support for immutable variables and conditional expressions would solve this.

Mutative Boilerplate

A post about mutation in Go would be remiss not to mention the current lack of generics. I’ve talked about this in the past, and generics are currently on their way, so I’m not going to beat a dead horse here, other to say that a lack of generics leads to mutative boilerplate which is error-prone and hard to read.

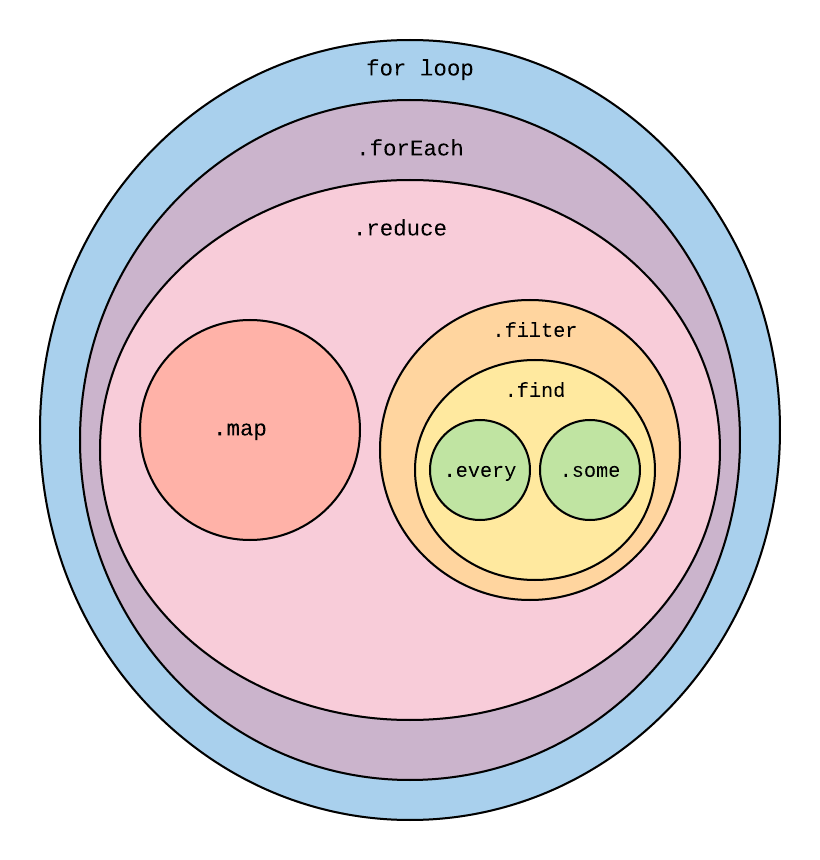

I’ve written before about using the least powerful tool for the job in the context of collection functions (map, filter reduce, etc), and how your code becomes more readable when you use, say, a map instead of a for loop. In the diagram I used for that post, Go only really provides the for loop and forEach functionality (via therange operator), meaning everything else is off the cards:

This means that instead of doing this:

userNames := users.map(func (u User) string { return u.Name }) // invalid syntax

we have to do this:

// backing array starts with a length of `len(users)` with

// each element being an empty string

userNames := make([]string, len(users))

for i, user := range users {

userNames[i] = user.Name

}

Or is it more efficient to do this?

// backing array starts empty but has the capacity of `len(users)`

userNames := make([]string, 0, len(users))

for _, user := range users {

userNames = append(userNames, user.Name)

}

Why do I even need to care about which of those two approaches is more efficient? All I want to do is map from a slice of users to a slice of their names. Just like with the examples of the previous section, you need to read the whole block of code to understand oh this is just doing a map and there’s nothing stopping me from making the mistake of going:

userNames := make([]string, len(users))

for i, user := range users {

userNames = append(userNames, user.Name)

}

Which looks fine but would actually give me a completely incorrect result. Coincidentally I actually made this exact mistake myself in the previous post before being corrected in the comments.

Yes, generics are on their way, but as I said at the beginning of this series, I’m voicing my grievances about today’s Go, not tomorrow’s. Generics were originally set for release in August, and now I doubt they’ll be out by the end of the year.

Conclusion

Mutation is inherent to Go programs, which decreases the code’s expressiveness and increases your difficulty as both a reader and writer of Go code. Doubtless there are probably people out there who find immutable variables and conditional expressions and map/filter/reduce more confusing than what Go’s curated feature set, and that’s fine, but I’m not one of them.

As with basically all of these posts, there are solutions to solve these problems (conditional expressions, immutability keywords), but I doubt Go has the appetite for them given the inherent complexity bump, and once again, this comes down to a difference in values.

Next up, Crazy Conventions.

Addendum

I haven’t touched on immutable types here, but if you want to get a feel for that, here’s a very extensive proposal for them. Given that immutability would be opt-in, this is one of the few times I actually think a proposal might add too much complexity for the benefits.

Go'ing Insane Series

Post 5 of 6.

Shameless plug: I recently quit my job to co-found Zenbu, a web app that helps you manage your company's SaaS subscriptions. Your company is almost certainly wasting time and money on unused subscriptions and Zenbu can fix that. Check it out at zenbu.au