Gaining Ground Without Generics In Go

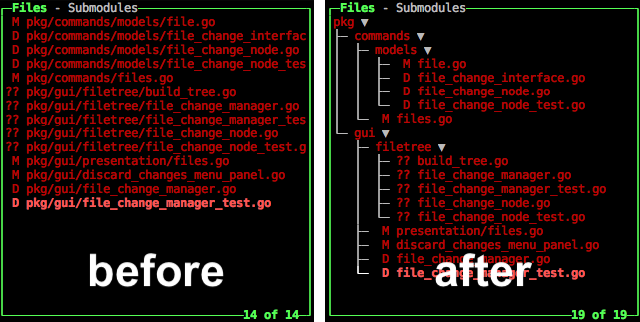

Recently I’ve been working on a feature in my open-source pride and joy, Lazygit, that allows viewing your modified files as a tree rather than a flat list. This allows you to get a better feel for which areas of the codebase have been changed, and has some perks like easy navigation with folder collapsing, and the ability to stage/unstage whole directories.

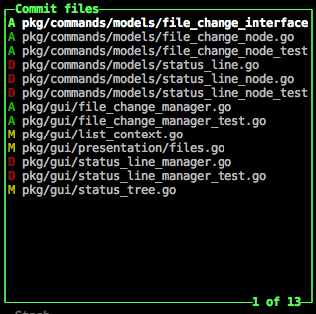

I got it all working for the ‘Files’ panel, which shows files in your working tree, but not in the ‘Commit-Files’ panel, which shows the changed files in a selected commit. In both cases I want the same logic when it comes to traversing the three, expanding/collapsing folders, etc, but the files themselves need to be rendered differently (in your working tree you want to see both staged and unstaged changes, whereas in the commit-files panel you just want to know whether the file was added, modified, or deleted).

This begs the question: how do we actually do this in Go? What I have is a Node struct which contains a key, a slice of Node children, and a pointer to a File which is non-nil when the Node is a leaf in the tree:

type File struct {

path string

isTracked bool

hasStagedChanges bool

hasUnstagedChanges bool

}

type Node struct {

children []*Node

key string

file *File

}

The node struct has all my logic for finding specific nodes, flattening the tree, etc:

func (n *Node) Find(test func(*Node) bool) *Node {

if test(n) {

return n

}

for _, child := range n.children {

match := child.Find(test)

if match != nil {

return match

}

}

return nil

}

func (n *Node) Flatten() []*Node {

result := []*Node{}

result = append(result, n)

for _, child := range n.children {

result = append(result, child.Flatten()...)

}

return result

}

This all works fine: see the following demo program:

func main() {

root := &Node{

key: "root",

children: []*Node{

{key: "child", file: &File{path: "root/child", hasUnstagedChanges: true}},

},

}

match := root.Find(func(n *Node) bool {

return n.file != nil && n.file.hasUnstagedChanges

})

// printing the matched file

fmt.Println(match.file.path)

// printing the flattened tree

for _, n := range root.Flatten() {

fmt.Println(n.key)

}

}

Okay, so what should I do if I want to support a tree of another kind of struct: CommitFile?

const (

ADDED ChangeType = iota

DELETED

MODIFIED

)

type CommitFile struct {

path string

change ChangeType

}

Well, now I’m in trouble. Go is yet to support generics, so I’ll need to come up with some alternative that doesn’t have me angering the programmer gods above. Here are some possibilities:

Solution 1: Use a map

With this approach we pull File out of the Node struct, and maintain a mapping on the outside from path to File. This would force me to barter in paths, not nodes: meaning I would need to return a path from my Find method and look up that path in my fileMap. This is quite painful if my nodes themselves don’t store paths but rather folder names; meaning I would need to construct the path to the file recursively:

type Node struct {

children []*Node

key string

}

func (n *Node) Find(test func(string) bool) (string, bool) {

// we're passing the path so-far into this method now, but we don't want to

// expose that to the caller so we're wrapping an auxilliary function here

return n.findAux(test, "")

}

func (n *Node) findAux(test func(string) bool, parentPath string) (string, bool) {

// let's hope this works

var path string

if parentPath != "" {

path = parentPath + "/" + n.key

} else {

path = n.key

}

if test(path) {

return path, true

}

for _, child := range n.children {

matchingPath, found := child.findAux(test, path)

if found {

return matchingPath, true

}

}

return "", false

}

func main() {

fileMap := map[string]*File{

"root/child": {path: "root/child", hasUnstagedChanges: true},

}

root := &Node{

key: "root",

children: []*Node{

{key: "child"},

},

}

path, found := root.Find(func(path string) bool {

file := fileMap[path]

return file != nil && file.hasUnstagedChanges

})

if found {

fmt.Println(fileMap[path])

}

}

I think it’s safe to say that this approach is quite painful: every time I want to use my Find method I need to do two lookups in fileMap: one for when we’re inside the callback, and one for when we’ve found our matching path and want to fetch the corresponding file.

We could make this slightly easier for the caller by having our Find function receive the filePath and do the conversion itself, but this is also awkward: it means we have the full file mapping available within the Find function despite that function only caring about the current node in the tree, in effect violating the principle of least privilege.

Solution 2: Use an interface

Okay so a map has proven fairly clunky. Perhaps an interface can save us?

type INode interface {

GetChildren() []INode

GetKey() string

}

func find(node INode, test func(n INode) bool) INode {

if test(node) {

return node

}

for _, child := range node.GetChildren() {

match := find(child, test)

if match != nil {

return match

}

}

return nil

}

So far so good: we don’t actually have any mention of our Node struct yet, because our find function simply acts on the INode interface with no regard for what concrete type lies underneath.

Go uses ducktyping for interfaces meaning that in order to implement the INode interface for my Node all I have to do is implement the GetKey() and GetChildren methods, so let’s do that:

// easy enough

func (n *Node) GetKey() string {

return n.key

}

// also easy

func (n *Node) GetChildren() []INode {

return n.children

}

Alright, now we can move on to… hang on, looks like we have a compiler error:

cannot use n.children (variable of type []*Node) as []INode value in return statement

That’s strange, it doesn’t seem to think that our *Node implements INode. What’s going on? It turns out that you can’t just treat a slice of structs as a slice of interface values, because the two things have different memory layouts: an interface value encodes both the type of concrete value, and the concrete value’s data, whereas a struct just contains its own data. For this reason, we need to manually construct a slice of interface values in our GetChildren() method:

func (n *Node) GetChildren() []INode {

result := make([]INode, len(n.children))

for i, child := range n.children {

result[i] = child

}

return result

}

Now, we could use our find function above and pass in our root to obtain the match, but just like in the example with the fileMap, we need to do some extra lifting both inside the callback and outside the function:

func main() {

root := &Node{

key: "root",

children: []*Node{

{key: "child", file: &File{path: "root/child", hasUnstagedChanges: true}},

},

}

match := find(root, func(node INode) bool {

// type assertion that we're dealing with a *Node value

castNode := node.(*Node)

return castNode.file != nil && castNode.file.hasUnstagedChanges

})

// type assertion that we're dealing with a *Node value

castMatch := match.(*Node)

fmt.Println(castMatch.file)

}

This truly sucks, but we can spare the calling code that suckery by wrapping the find function in a Find method that encapsulates all the type-casting:

func (n *Node) Find(test func(n *Node) bool) *Node {

match := find(n, func(node INode) bool {

castN := node.(*Node)

return test(castN)

})

return match.(*Node)

}

func main() {

root := &Node{

key: "root",

children: []*Node{

{key: "child", file: &File{path: "root/child", hasUnstagedChanges: true}},

},

}

match := root.Find(func(node *Node) bool {

return node.file != nil && node.file.hasUnstagedChanges

})

fmt.Println(match.file)

}

I see this as an improvement upon the fileMap approach, however it has its own downsides:

Type Assertions

In the world of statically typed languages, type assertions are a cheat: we’re telling the compiler that we know best and it’s taking our word for it. I could accidentally cast to some other struct which implements the INode interface and we would have our program panic at runtime. The whole point of statically typed languages is to pull errors out of runtime land into compile-time land where they’re not going to affect end-users.

Boilerplate

There’s quite a bit of boilerplate required for any struct that wants to implement the INode interface and make use of its functions. If I wanted to add a CommitFileNode struct which stored a CommitFile rather than a File, I’d end up duplicating quite a bit of code:

type CommitFileNode struct {

children []*Node

key string

commitFile *CommitFile

}

func (n *CommitFileNode) GetChildren() []INode {

result := make([]INode, 0, len(n.children))

for i, child := range n.children {

result[i] = child

}

return result

}

func (n *CommitFileNode) GetKey() string {

return n.key

}

func (n *CommitFileNode) Find(test func(n *CommitFileNode) bool) *CommitFileNode {

match := find(n, func(node INode) bool {

castN := node.(*CommitFileNode)

return test(castN)

})

return match.(*CommitFileNode)

}

Look familar? There’s almost enough boilerplate here to justify duplicating the Find method itself and scrapping the idea of sharing any code between the two structs. For each new function we add, we’ll need a corresponding wrapper that applies the type assertions, e.g:

func flatten(node INode) []INode {

result := []INode{}

result = append(result, node)

for _, child := range node.GetChildren() {

result = append(result, flatten(child)...)

}

return result

}

func (n *Node) Flatten() []*Node {

results := flatten(n)

nodes := make([]*Node, 0, len(results))

for i, result := range results {

nodes[i] = result.(*Node)

}

return nodes

}

func (n *CommitFileNode) Flatten() []*CommitFileNode {

results := flatten(n)

nodes := make([]*CommitFileNode, 0, len(results))

for i, result := range results {

nodes[i] = result.(*CommitFileNode)

}

return nodes

}

Solution 3: Generics?

In conclusion: life sucks. The good news is that Go should be getting generics this year and we can already battletest them in a playground

Here’s how it would look:

We start by defining our generic Node struct:

type Node[T any] struct {

children []*Node[T]

key string

obj T

}

In most languages we use angle brackets <> to denote type parameters but here we use square brackets. We’re saying that Node is a struct that is generic over the type parameter T, which has no constraints (hence the any keyword).

In this struct definition we’re saying that whatever object the node contains, its children must also contain objects of the same type.

Now we can write our Find function in a generic way:

func (n *Node[T]) Find(test func(*Node[T]) bool) *Node[T] {

if test(n) {

return n

}

for _, child := range n.children {

match := child.Find(test)

if match != nil {

return match

}

}

return nil

}

We don’t actually need to reuse the ‘T’ type parameter here, we’re just doing it for consistency. We could have called it Object.

In the method signature we’re saying that the method is defined on our generic type *Node and that whatever test callback is passed to the Find method needs to deal with the same kind of Node. Likewise, the node returned will include the same type.

Now we can actually test this:

func main() {

root := &Node[*File]{

key:"root",

children: []*Node[*File]{

{

key: "child",

obj: &File{path: "root/child", hasUnstagedChanges: true},

},

},

}

match := root.Find(func(n *Node[*File]) bool {

return n.obj != nil && n.obj.hasUnstagedChanges

})

fmt.Println(match.obj.path)

}

Admittedly, the requirement to include the type parameter [*File] in three separate places makes the code a little more cluttered, but I expect that when generics are officially released we’ll get better type inference and the compiler can spare us having to overspecify.

At any rate, this is pretty good! It’s trivially easy to support our CommitFile struct as well:

func main() {

root := &Node[*CommitFile]{

key:"root",

children: []*Node[*CommitFile]{

{

key: "child",

obj: &File{path: "root/child", change: ADDED},

},

},

}

match := root.Find(func(n *Node[*CommitFile]) bool {

return n.obj != nil && n.obj.change == ADDED

})

fmt.Println(match.obj.path)

}

No extra boilerplate required!

The Long Wait

There are some existing tools out there that generate code to substitute for actual generics, but I don’t want to add an extra step to the dev process because it’s hard enough being an open source contributor as it is! Which means I’m stuck with the awkward type-assertion approach for now, until generics finally land in the actual language.

I hope you share in my excitement for generics, hope you share in my pain without them, and most of all, I hope you share this post if you know somebody who might be looking for a workaround in a genericless world, as The Long Wait draws nearer to an end.

Shameless plug: I recently quit my job to co-found Zenbu, a web app that helps you manage your company's SaaS subscriptions. Your company is almost certainly wasting time and money on unused subscriptions and Zenbu can fix that. Check it out at zenbu.au