Array Functions and the Rule of Least Power

The Rule of Least Power

In 1998, Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web, coined the Principle of Least Power:

Computer Science in the 1960s to 80s spent a lot of effort making languages which were as powerful as possible. Nowadays we have to appreciate the reasons for picking not the most powerful solution but the least powerful.

In 2006, The W3C codified the principle as the Rule of Least Power:

There is an important tradeoff between the computational power of a language and the ability to determine what a program in that language is doing

Expressing constraints, relationships and processing instructions in less powerful languages increases the flexibility with which information can be reused: the less powerful the language, the more you can do with the data stored in that language.

In fact, Berners-Lee chose not to make HTML a bona-fide language on the basis of this rule:

I chose HTML not to be a programming language because I wanted different programs to do different things with it: present it differently, extract tables of contents, index it, and so on.

Though the Rule of Least Power targeted programming languages themselves, rather than language features, I think the same ideas still apply. The less powerful your code is, the easier it is to reason about.

Array Functions

It’s therefore interesting that some people say say that the ‘functional’ array functions like .filter, .map, and .reduce are powerful compared to their crude for-loop alternatives. I would say the opposite: they are far less powerful, and that’s the point.

No doubt, the people calling these functions ‘powerful’ are probably referring to their power in aggregate (for example being able to call array.map(...).filter(...)), or the power enabled through parallel processing, or the power afforded by assigning callbacks to first-class function variables.

But I want to bring your attention to how the power of these functions when considered individually is in fact low, by design.

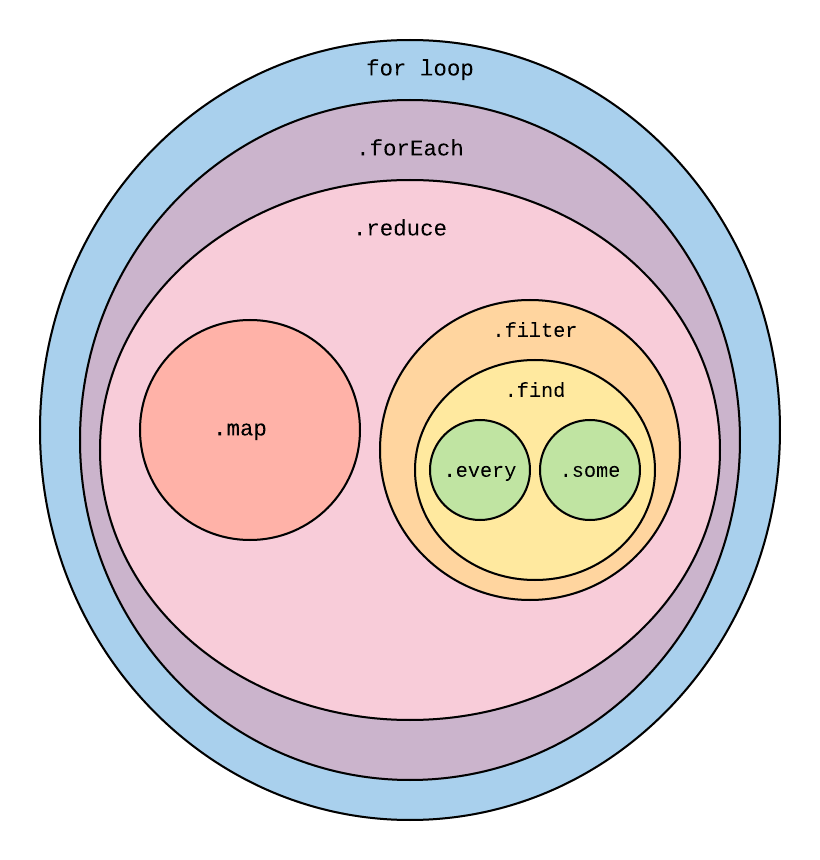

Here is a diagram I whipped up that crudely orders the common javascript array functions, going from the most powerful (a for-loop) to the least powerful (.some/.every).

Array Function Recap

Before explaining what I mean by powerful, here’s a quick recap of what the different approaches are actually for:

- for-loop: iterate through a chunk of code, typically for the sake of creating side effects inside the loop (like appending to an array)

.forEach: iterate through each element in an array, and in each iteration do something with that element. Again, typically for the sake of creating a side effect at some point.

From here down, side effects are strongly discouraged

.reduce: from left-to-right, iterate through an array to accumulate some value, potentially initialized explicitly at the start, where in each iteration we take the current array item and return the new value of the accumulator (until we return the final value at the end).map: for each original item in the array, return a new item as a function of the original item to be placed in the corresponding index of the output array.filter: from left-to-right, for each item in the array, include it in the output array if it satisfies some condition.find: from left-to-right, return the first item in the array satisfying some condition.every: return true if every item in the array satisfies some condition, otherwise return false..some: return true if any item in the array satisfies some condition, otherwise return false.

This post is less about explaining what each one does and more about picking which one to use. For a good reference see here

What Do You Mean By Powerful?

I’m piggybacking off Tim Berners-Lee’s coinage here, but when I say ‘powerful’, I really mean ‘flexible’. As in, how many use cases can this function satisfy? Specifically, I’m defining function A as being more powerful than function B if it can implement function B in its own terms, and do other stuff too that function B can’t.*

Which means by my definition (which I’m not claiming to be universal) a for-loop is more powerful than .forEach because you can implement .forEach via a for-loop. For example:

const forEach = (array, callback) => {

for (i = 0; i < array.length; i++) {

callback(array[i]);

}

};

forEach([1, 2, 3], a => console.log(a)); // prints: 1,2,3

[(1, 2, 3)].forEach(a => console.log(a)); // prints: 1,2,3

So no matter what .forEach can do, a for-loop can do more.

Likewise, .reduce can be implemented with .forEach like so:

const reduce = (array, callback, initialValue) => {

let result = initialValue;

array.forEach(item => {

result = callback(result, item);

});

return result;

};

reduce([1, 2, 3], (acc, curr) => acc + curr, 0); // equals 6

[(1, 2, 3)].reduce((acc, curr) => acc + curr, 0); // equals 6

And so on, and so on, all the way to the bottom:

const some = (array, callback) => array.find(callback) !== undefined;

Notably, our custom some doesn’t handle undefined values as well as the ECMASCript one, but you get the idea.

Choose the Least Powerful Function

Why not just use a for-loop for everything? That way we only need to remember one approach to iterating through an array’s items. The reason is the same reason you don’t use a grenade to kill a mosquito: grenades are illegal and black market goods are marked up to subsidise the risk taken on by the vendor.

For real though: there are various reasons to pick the least powerful tool, but to me the two most important reasons are:

- reducing the chance of errors

- easy comprehension by others

Reducing the chance of errors

The least powerful tool for the job that can still do the job is the one that leaves the least chance for errors. Consider the situation where I have an array of numbers and I want to return the result of doubling each item in the array:

const myArray = [1, 2, 3];

// with `.map`

resultWithMap = myArray.map(item => item * 2); // equals: [2, 4, 6]

// with a for-loop

let resultWithLoop = [];

for (i = 0; i < myArray.length - 1; i++) {

resultWithLoop.push(array[i] * 2);

}

resultWithLoop; // equals: [2, 4]

Hey, what the hell? Why is my resultWithLoop missing an item? I started my index at zero, I only incremented one at a time, and I’m ensuring I don’t have an out of bounds error by ensuring I don’t include the element at index myArray.length.

Oh wait, that < in my for-loop should be a <= (or I could remove the -1 from myArray.length-1). My mistake.

The for-loop is too powerful to care about what you’re actually using it for. Maybe you actually did want to exclude the final element, how could it know? Luckily we caught this one early, but whether you’re missing an = or missing a grenade pin, sometimes by the time you realise your mistake, it’s already too late.

The reason .map is the appropriate choice here is because it is an abstraction that hides the control flow of looping through each item in a list, meaning it’s impossible for you to get it wrong. When you use .map, you are guaranteed that the result will have as many elements as the original map, and that each element in the output array is a function only of the corresponding element in the input array**.

Easy comprehension by others

comparing the for-loop approach and the .map approach above, which is easier to parse as a reader? If you’re only familiar with for-loops, you’ll pick that, but given the ubiquity of .map in programming languages today, it’s probably time to learn it. For those familiar with both, the .map approach is far easier to read:

- You don’t need to read through how the

ivariable is manipulated in the for-loop, because that’s abstracted away. - You know what the shape of the output will be.

- You don’t need to worry about whether your original variable is being mutated in each iteration.

Without even looking at the callback function passed to .map you know a great deal about what to expect from the result. The same cannot be said of the for-loop.

Likewise, say I have an array of fruits and I want to know if it contains any apples. Here’s a few approaches:

const fruits = ['orange', 'pear', 'apple', 'apple', 'peach'];

const hasAppleViaFilter = fruits.filter(fruit => fruit === 'apple').length > 0; // equals: true

const hasAppleViaFind = fruits.find(fruit => fruit === 'apple') !== undefined; // equals: true

const hasAppleViaSome = fruits.some(fruit => fruit === 'apple'); // equals: true

Each approach is ordered by decreasing power. Notice that .some is the easiest on the eyes? As soon as you see .some you know that hasAppleViaSome will be assigned a boolean value, based on the callback fruit => fruit === 'apple'. In the filter approach, you need to mentally store the fact that we’re creating an array with a subset of the original array’s fruits, and then we’re checking the length of it, and comparing with zero. Only once you parse all of that do you realise the actual implicit intention, which happens to be the same as the explicit intention of the .some method.

These are just small examples, but when you have a big hairy callback with heaps of code inside, the reader can see that it’s still just a call to .some and can rest assured that all the callback will do is return true or false. This calibrates the expectations of the reader and makes it easier to process what is happening inside the callback.

const hasAppleViaContrivedSome = fruits.some(fruit => {

if (typeof fruit !== 'string') {

return false;

}

if (fruit === 'pear') {

return false;

}

if (fruit === 'orange') {

return false;

}

if (fruit === 'forbidden fruit') {

return false;

}

if (fruit.substring(1, 4) === 'pple') {

return fruit === 'apple';

}

return false;

});

On the other hand, when somebody comes across your code and sees a powerful function used to perform something as trivial as a .some call, they’re going to be more confused than the time they stumbled upon a grenade in the place you usually keep the fly swatter.

With Little Power Comes Great Responsibility

Hardcore functional languages like Haskell will not allow side effects inside a function, meaning the order in which you process items in a .map makes no difference to the output, and so you can boost efficiency by running the callback calls in parallel. This is not true of javascript: side effects are permitted by the language in all the abovementioned functions.

So what’s the harm in sneaking some side effects into a callback to one of these functions? Say you’re checking if we have an apple in our list of fruits, but you want to also append the index of any oranges you come across to an orangeIndexes array. You might be tempted to do this:

const fruits = ['orange', 'pear', 'apple', 'apple', 'peach'];

let orangeIndexes = [];

const hasApple = fruits.some((fruit, index) => {

if (typeof fruit !== 'string') {

return false;

}

if (fruit === 'pear') {

return false;

}

if (fruit === 'orange') {

orangeIndexes.push(index); // surely some mutation can't hurt

return false;

}

if (fruit === 'forbidden fruit') {

return false;

}

if (fruit === 'apple') {

return true;

}

return false;

});

hasApple; // equals: true

orangeIndexes; // equals: [0]

No. This is really bad. By mutating a variable inside our .some call, we’re misleading the reader into thinking that the callback conforms to the expected behaviour of simply returning true or false based on the fruit, when in fact it’s directly messing with variables outside the scope of the callback. At best this proves momentarily confusing, at worst it weakens the reader’s trust that the next ‘low-power’ function they encounter will be true to its name.

When in this situation, you have two choices:

- switch to a more powerful function and stop lying to your reader

- find a cleaner way to achieve the desired behaviour

Option 1 might look like this:

const fruits = ['orange', 'pear', 'apple', 'apple', 'peach'];

let orangeIndexes = [];

let hasApple = false;

fruits.forEach((fruit, index) => {

if (typeof fruit !== 'string') {

return;

}

if (fruit === 'pear') {

return;

}

if (fruit === 'orange') {

orangeIndexes.push(index);

return;

}

if (fruit === 'forbidden fruit') {

return;

}

if (fruit === 'apple') {

hasApple = true;

return;

}

});

hasApple; // equals: true

orangeIndexes; // equals: [0]

At least now the reader enters the forEach callback knowing what they’re in for.

Option 2 might look like this:

const fruits = ['orange', 'pear', 'apple', 'apple', 'peach'];

const orangeIndexes = fruits.reduce(

(acc, curr, index) => (curr === 'orange' ? acc.concat(index) : acc),

[]

);

const hasApple = fruits.some(fruit => fruit === 'apple'); // equals: true

orangeIndexes; // equals: [0];

I’m not saying option 2 is better than option 1. Sometimes, for all its correctness, a functional solution can simply be much harder to read than a mutative alternative, particularly in dynamically-typed languages.

What I’m saying is that both option 1 and 2 are vastly superior to the half-functional half-mutative code we started with: the important take away here is that from .reduce down to .some, side effects in callbacks erode the expressive power of these functions to communicate the writer’s intent and make for more difficult reading than that news article about the domestic grenade explosion in mosquito season.

In Defense of the for-loop

Having made lazygit and lazydocker, I’ve spent quite a lot of time in the world of Go, where there are no maps, filters, or reduces. Although I’ve panned the for-loop a fair bit in this post, it’s worth noting that a language mandating for-loops has some advantages:

- it’s easier to learn one control structure than all the different functions in this post

- when speed matters, for-loops with mutative side effects can be faster than functional alternatives

- in a typed language, map/filter/reduce require generic types, which makes for a more complex type system meaning slower compile times and a steeper learning curve.

Having said all that, oh my god I cannot wait until Go introduces generics and I no longer need to write a for-loop to check if an array of fruits contains an apple.

When Life Gives You Apples

If you have the luxury of using a language which does support filter/map/reduce and friends, use them!

If you’re in a dynamically-typed language, sometimes a judgement call is required to pick between a mutative approach that exposes the underlying types and a functional approach which is harder to parse (e.g. .reduce vs .forEach).

But whether you’re writing code or hunting mosquitoes, if there’s anything to take away from this post, its to always ask yourself:

could I use a less powerful tool to achieve the same result?

Thanks for reading!

Addendum #1: Strength In Numbers

Earlier I said that I wanted to focus on how individual array functions are low-power, even if their composition proves high-power. This begs the question: are there times when a composition of array functions proves too powerful and hinders rather than helps the reader’s comprehension?

Here’s an example that roughly mimics a real situation I’ve encountered: say we have a system which keeps track of product clicks on a website via a productClick model, which references the product and the customer who clicked on it. We want a function, which when given an array of productClick ids, returns an array of objects containing the product and the customer (no need for the click object itself to be included). We must also skip any clicks whose customer/product cannot be found.

Say that we have some functions to help us out here:

fetchProductClick: (productClickId: number) => ProductClick | null;

fetchProduct: (productClick: ProductClick) => Product | null;

fetchCustomer: (productClick: ProductClick) => Customer | null;

And let’s also assume these functions are somewhat expensive to run, but that the ticket for adding functions for bulk fetching of data is deep in the backlog and we don’t have time to address that right now.

Here’s how you would do it using .forEach:

const fetchProductClickInfo = productClickIds => {

let results = [];

productIds.forEach(productClickId => {

const productClick = fetchProductClick(productClickId);

if (productClick === null) {

return;

}

const product = fetchProduct(productClick);

if (product === null) {

return;

}

const customer = fetchCustomer(productClick);

if (customer === null) {

return;

}

results.push({

product,

customer,

});

});

return results;

};

We’re making use of an early return whenever an object isn’t found, and at the end if we have the product and the customer we chuck them into the result array.

You might say that we could do the same thing with a .reduce without it being any less readable, and I would agree. But why stop at reduce? You can also achieve the same behaviour by composing .map and .filter like so:

const fetchProductClickInfo = productClickIds =>

productClickIds

.map(productClickId => fetchProductClick(productClickId))

.filter(productClick => productClick !== null)

.map(productClick => ({

productClick,

product: fetchProduct(productClick),

}))

.filter(productClickInfo => productClickInfo.product !== null)

.map(productClickInfo => ({

product: productClickInfo.product,

customer: fetchCustomer(productClickInfo.productClick),

}))

.filter(productClickInfo => productInfo.customer !== null);

Okay so not only is this harder to read than the example with the .forEach loop, it’s actually introducing complexity that has nothing to do with the requirements. For every object we fetch we need to stop the process if we didn’t find it, meaning every .map must be followed by a .filter checking for a null value. This means we’re looping through the array far more than necessary.

We don’t want to fetch both the product and the customer in the same .map callback in case the product is null, which would make fetching the customer (an expensive operation) redundant.

What’s more, despite the fact that we don’t want to include the productClick in the final result, we still need to thread it through the second .map so that we can use it to fetch the customer in the third .map. What a headache!

The lesson to take away here is that although some individual functions could be low-power, that doesn’t mean a composition of those functions is itself low-power. And if the required behaviour calls for something high-power, you need to think carefully about which approach introduces the least amount of extrinsic complexity. Just because you’re more familiar with .map and .filter than that scary .reduce does not mean you should use them when a .reduce is more appropriate (or even a for-loop).

Addendum #2: Benchmarks

In my personal experience, performance has never been a big deal when comparing these approaches, as I’ve found:

- in a frontend application you’re rarely dealing with large arrays

- in a framework like React, slowness typically comes from unnecessarily performing some operation with each render when it only needs to be done once, meaning the

useMemohook is a better solution than changing how you process the data.

But there are plenty of times when performance does matter in javascript. So I’ve used Benchmark.js to do some benchmarks comparing how different approaches perform when doing a map operation:

For an array of 1000 numbers in ascending order, incrementing the item in each iteration, here are the results:

map x 386,175 ops/sec ±13.96% (91 runs sampled)

reduce x 257 ops/sec ±1.34% (85 runs sampled)

forEach x 193,596 ops/sec ±0.78% (92 runs sampled)

for-loop x 190,224 ops/sec ±0.36% (96 runs sampled)

for-loop in-place x 444,796 ops/sec ±0.61% (93 runs sampled)

forEach in-place x 805,311 ops/sec ±19.99% (92 runs sampled)

Fastest is forEach in-place

If in-place mutation is off the table, .map is by far superior to the alternatives for simple transformations like incrementing numbers. If you allow for in-place mutation of the original array, forEach takes the cake, being roughly twice as fast as both .map and the in-place for loop.

For an array of 1000 objects, merging a key/value pair in each iteration, we get:

map x 48,774 ops/sec ±11.75% (86 runs sampled)

reduce x 215 ops/sec ±2.39% (83 runs sampled)

forEach x 45,489 ops/sec ±2.12% (92 runs sampled)

for-loop x 48,263 ops/sec ±4.41% (93 runs sampled)

forEach in-place x 3,440 ops/sec ±0.69% (90 runs sampled)

for-loop in-place x 3,430 ops/sec ±1.31% (91 runs sampled)

Fastest is for-loop

So when the transformation requires creating a new object e.g. when merging a key/value pair into an object, everything is slower, but the for-loop is the fastest. The in-place .forEach and for-loop approaches are notably quite slow compared to in the previous case. I suspect this is because objects don’t have fixed size, meaning replacing an object at a given index in an array full of objects is a more expensive operation than simply appending to a new array. We might see an increase in speed if we were simply overwriting a single key on the object rather than replacing the object with a new one in each iteration.

In all cases, reduce is the slowest by a large margin. This would be because it has to recreate a new array in each iteration and populate it. No doubt in situations where it’s cheaper to create the new value of the accumulator, the difference would not be as steep.

I whipped up these benchmarks without putting too much effort in, so don’t take this as a definitive result. Whenever performance matters, the responsibility is on you to benchmark! Small changes to the expected data/behaviour can cause large discrepancies in performance between different approaches.

Appendix

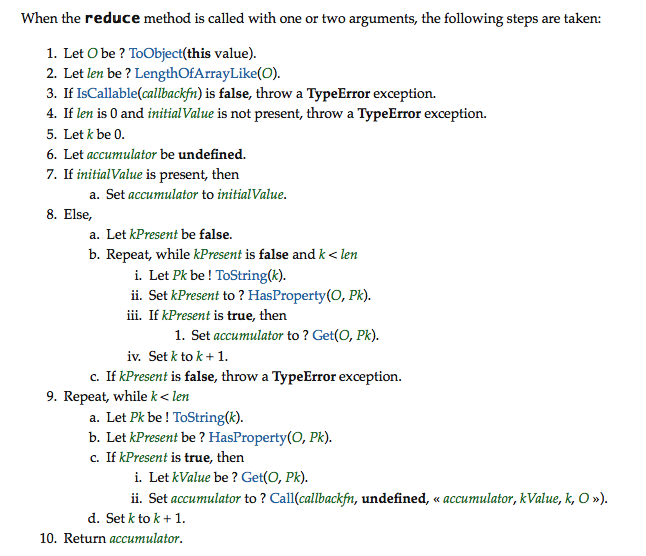

*There are edge cases, for example .find doesn’t quite implement .some given the case that there are undefined values in the array. But this post is more about asking the question of, whether for a given case, you can pick the less powerful tool. Also, Examples are purely illustrative. Here is the actual pseudocode for .reduce from the 2020 ECMAScript language spec (pretty gnarly)

** exception being if we reference the array itself inside the callback, or any other variable outside the scope of the callback. Which would beg the question of why we’re using a .map in the first place.

Shameless plug (which appears on every blog post, not just this one, so don't think that I'm opportunistically posting this specific post just for the sake of doing this plug): I recently quit my job to co-found Subble, a web app that helps you manage your company's SaaS software licences. Your company is almost certainly wasting time and money on shadow IT and unused/overprovisioned licences and Subble can fix that. Check it out at subble.com