Backpedal of the Day: Type Keys

Recently I wrote a post on type keys which a reader of the blog posted to Reddit where it was generally well-received, but garnered enough feedback for me to promote type keys from ‘anti-pattern’ to ‘code-smell’, and include a counter-example where type keys were the lesser of all evils. The post to Hacker News gained no traction but I was satisfied enough with the feedback from Reddit.

Then a little while later, a Hacker News mod sent me an email inviting me to repost, so I excitedly posted my new-and-improved version, only to find it also gained no traction. Oh well, such is life. Then I decided to check back a day later on a whim and to my surprise the post had actually landed 70 upvotes. But reading through the comments I had a Roman moment as I realised that the post had been absolutely crucified.

And so we come to today’s post, which is my attempt to gain back some favour from the internet and refine my thesis. I am left with no choice but to promote type keys once more, this time to ‘it depends’.

There are three main criticisms the original post received:

- Type keys are sometimes necessary

- Switch statements need to live somewhere

- Removing type keys can obscure code

Let’s walk through each of these and see if we can update the original contention accordingly:

Type keys are sometimes necessary

To recap, the original post defined a type key by four criteria:

- its value is always known at compile time. We’re not receiving it as an parameter from an HTTP request or a value from the database.

- its expected to have one of a finite set of values i.e. it’s basically an enum.

- given that it’s basically an enum, its actual value is meaningless: it will never be written anywhere or compared to another variable’s value

- inside the function, the argument is only used in a switch-statement (if-statements count too) i.e. the value only affects the control flow of the function

This caused some confusion because most people consider points 2, 3, and 4 to be sufficient for identifying a type key. Saying that point 1 is a requirement begs the question of what name you would use if that point wasn’t satisfied. My bad. Let’s go with the conventional definition and we’ll say that if point 1 is satisfied we’re dealing with a special kind of type key: a static type key, that is, a type key whose value can always be determined at compile time.

If we ignore static type keys, there are two common situations where type keys are always a good idea: serialization and union narrowing.

Serialization

Unlike most data, functions cannot (easily) be stored on a disk or transferred over a network. If you are a server that needs a user to authenticate before running some function, you can’t just pass the function back to the client to be executed after authentication. Instead, you need to find some way of identifying a function (typically with a string) and pass that string to the client along with any variables it needs, so that the client can pass that data back later for the process to be continued. Hacker News uses this approach itself i.e the client passes back the action type key to the server:

{

"action": "POST_COMMENT",

"content": {

"thread_id": 1234,

"text": "Fuck you Jesse, maybe do some research next time before you try to vilify type keys regardless of situation!" // fair call

}

}

And then in the server we have:

switch action {

case "POST_COMMENT" {

postComment(content.thread_id, content.text)

...

}

When we take a general function and replace it with a mapping from identifiers (type keys) to function calls, we call this de-functionalisation and the reverse operation is called re-functionalisation.

Given that in various situations it is basically impossible to send a function over the wire, the use of a type key here is your only option and therefore it makes no sense to criticise that choice. After all, the whole point of a type key is to say ‘some behaviour associated with this type lives elsewhere’.

But to reiterate: we’re not talking about static type keys here: the value can’t be known at compile time because we have no idea what value the client will pass to the server.

Union Narrowing

Another example of where type keys are useful is in union narrowing, a feature in languages like Typescript that allows you to take a discriminated union and narrow it down without making assertions about the resulting type.

Consider a Shape interface which could be a circle or a square. We could add a kind type key like so:

interface Shape {

kind: 'circle' | 'square';

radius?: number;

sideLength?: number;

}

But we run into trouble when trying to use this shape in, say, a getArea function. Ideally we could do something like the following:

function getArea(shape: Shape) {

switch (shape.kind) {

case 'circle':

return Math.PI * shape.radius ** 2; // Error: Object is possibly 'undefined'.

case 'square':

return shape.sideLength ** 2; // Error: Object is possibly 'undefined'.

}

}

But inside the leg of the circle case, Typescript doesn’t know that radius is defined, even though we know that it should be, given that we’re dealing with a circle. So we can instead use a union like so:

interface Circle {

kind: 'circle';

radius: number;

}

interface Square {

kind: 'square';

sideLength: number;

}

type Shape = Circle | Square;

and now our getArea function will be happy, because if we enter the ‘circle’ case, Typescript narrows the union down to just the Circle interface and now knows that our radius will always be defined.

You may ask the question: wouldn’t this problem go away if we simply made Circle and Square each their own classes, with their own getArea methods defined? This ties into the expression problem.

The Expression Problem

Going with our above geometry example, often you will find yourself with a set of types (circle, square, etc) along with a set of behaviours (getting the area, getting the perimeter, etc). Effectively we end up with a 2D table where columns are types and rows are behaviours

| square | circle | |

|---|---|---|

| getArea | Math.PI * radius ** 2 |

sideLength ** 2 |

| getPerimeter | Math.PI * radius * 2 |

sideLength * 4 |

The expression problem states that when you have various types and behaviours that apply to those types, if you don’t want to use a 2D structure like a table in your code, then you need to choose between having types which contain behaviours (i.e. classes containing methods like shape.getArea()) or behaviours which contain types (e.g. functions which take data structures as arguments, like getArea(shape)). With our above example, we need to choose between shape.getArea() and getArea(shape).

It’s generally considered good practice to choose the option that makes adding new code easier: do you expect to typically add more types over time, or more behaviours? If you expect to add more types, you should use classes, because supporting a new type is as simple as making a new class and implementing the interface. But if you expect to add new behaviours, you should use the functions-and-data-structures approach, because adding a new behaviour is as simple as adding a new function with a switch statement for all the possible types. Conversely, if you need to add new behaviour to a set of classes, that’s a lot of modifications across various classes, and if you need to add new types to a set of functions, that’s a lot of switch statements to update. This is effectively the open-close principle.

Although I rarely see situations where the functions-with-data-structures approach is preferable, there are certain domains where it makes complete sense (such as geometry and AST’s), and in those cases, if your language doesn’t let you directly check the type of a data structure (i.e. typeof shape == Circle), putting a type key in your data structures makes perfect sense.

Orthogonal Type Keys

Let’s say you have gone with functions and data structures, but you actually know each type at compile time and have good reason to believe you will always know each type at compile time. Why bother with the switch statements? That’s run-time code acting on compile-time knowledge. You could just as easily have one function per type per behaviour e.g. ‘getSquareArea’. But this begs the question: do we really want to go and write separate functions for ‘getSquareArea’, ‘getSquarePerimeter’, ‘getCircleArea’, ‘getCirclePerimeter’, etc? It feels a little redundant, and that’s because it is!

Most languages favour one side of the expression problem and not the other: if you take a classes-with-methods approach, the language handles the dispatching for you via subtype polymorphism i.e. if you call shape.getArea() the language works out which getArea() function should actually be called based on the type of the shape object. But if you take the functions-with-data-structures approach, you typically need to go and handle the dispatching manually by writing your own switch statement that decides which code to run based on the data structure passed into the function. Part of the reason why classes-with-methods are often preferred over functions-with-data-structures is because the typical language handles that dispatching for you.

Some languages, however, support function overloading which would let you define the getArea() function on a per-type basis like so:

// note that Typescript actually does not support this kind of function

// overloading (it lets you overload the signature, but not the implementation)

function getArea(circle: Circle) {

return Math.PI * shape.radius ** 2

}

function getArea(square: Square) {

return shape.sideLength ** 2

}

...

// compiler would know which getArea function to call based on shape's type

getArea(shape)

This would spare us from the awkwardness of coming up with a unique function name for every permutation of type and behaviour. The question is: what do we do when our language does not support function overloading, and we’ve decided that we want to use functions with data structures as opposed to classes with methods? We have two choices: per-type functions or functions with switch statements. If we don’t know the types at compile time, the switch statement is our only choice, but if we do, we can reduce complexity by defining per-type functions.

The per-type function approach becomes problematic, however, when you need to deal with two orthogonal type keys. As a contrived example, let’s say we have a sumArea(shape, shape) function which needs to sum the area of the two given shapes. Assuming function overloading is off the table, we could go and write one function for each permutation i.e. sumSquareAndCircleArea, sumSquareAndSquareArea, etc, but now we’re trading off the complexity of a switch statement for complexity in function definitions, and in this case I would opt for just using the switch statement.

To be honest, even in the case when we’re dealing with functions of a single argument like getArea I don’t mind the switch statement, if only because I can pin the blame on the language for forcing me to choose between two awkward alternatives.

Switch statements need to live somewhere

The second main criticism of the original post is that by doing away with a type key (and therefore losing a switch statement that switches on the type key) we’re just moving that complexity to the clients, meaning if there’s 50 call sites you now have 50 switch statements. There are two possibilites here:

- the clients have good reasons to be using type keys

- the clients have no good reason to be using type keys

If the clients have good reasons to be using type keys, chances are we are not dealing with static type keys, meaning it’s perfectly sensible to retain the type key and just have a single centralised switch statement. But if the clients are all dealing with static type keys, it’s worth seeing if the code could be simplified by dropping those type keys and just directly calling the appropriate functions, so that we can do away with the switch statements entirely. For example (taken from Lazygit) we can go from this:

function setBoldValue(on) {

if (on) {

setBold()

} else {

unsetBold()

}

}

...

setBoldValue(true)

...

setBoldValue(false)

to this:

setBold()

...

unsetBold()

This of course assumes you have control over the call sites.

If you don’t have control over the call sites because you’re writing library code, you could argue that it’s impossible to know the use case of your clients, so we should err on the side of using a type key to spare the clients from using their own switch statements (or conditionals in general). This makes sense when your type key is a boolean value, given that booleans are just glorified enums of only two values (true and false), and your clients don’t need to import that enum from your library to use it. But if you’re defining your own type key with the values of ‘circle’, ‘square’, etc, there’s a good chance that all your clients will need to implement switch statements regardless of whether you use a type key or not, given that they may need to take one representation of the type key and convert it into your exported representation, e.g.:

// in the library

export enum ShapeType {

Circle,

Square,

...

}

function createCircle() { ... }

function createSquare() { ... }

export function createShape(shapeType: ShapeType) {

switch (shapeType) {

case ShapeType.Circle:

createCircle()

case ShapeType.Square:

createSquare()

...

}

}

// in the client

import { ShapeType, createShape } from 'geometry'

...

switch (valueFromDB) {

case 'circle':

createShape(ShapeType.Circle)

case 'square':

createShape(ShapeType.Square)

...

}

We can reduce the complexity by having the client directly call shape-specific functions like so:

// in the library

export function createCircle() { ... }

export function createSquare() { ... }

// in the client

import { createCircle, createSquare } from 'geometry'

...

switch (valueFromDB) {

case 'circle':

createCircle()

case 'square':

createSquare()

...

}

At any rate, this is domain-specific, and it’s a judgement call as to whether the use of a type key here is valid, given the expected use cases of the clients.

Removing type keys can obscure code

The above sections have mostly dwelled on the distinction between regular type keys and static type keys, with static type keys being held in suspicion given they necessitate run-time logic (switches) to handle compile-time knowledge. Here we’re going to ignore that distinction and consider the argument that sometimes removing a type key, regardless of whether it’s static or not, simply results in code that’s harder to understand.

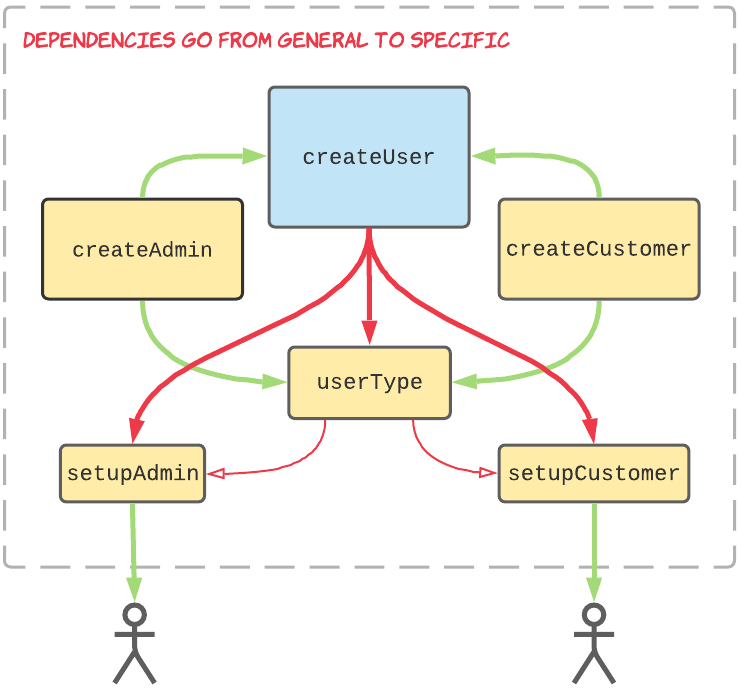

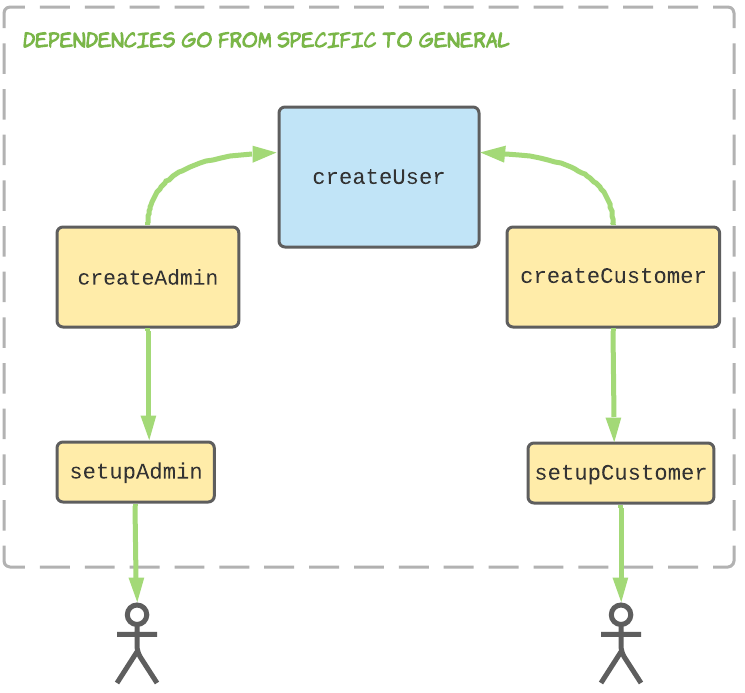

In the original post I made the case that removing type keys results in a cleaner dependency graph that makes code easier to maintain, using these before and after diagrams to demonstrate:

Before:

After:

Some commenters argued that removing a type key adds unnecessary complexity and obscures the intention of the code, dependency diagrams be damned!

The original post concedes this point with an example of where the type key is the lesser of all evils, but some took issue with the main example of the createUser function, which we end up passing an onCreate callback.

export const createAdmin = (attributes: UserAttributes): User => {

return createUser(attributes, setupAdmin);

};

// this function could be inlined if desired

export const createCustomer = (attributes: UserAttributes): User => {

return createUser(attributes, setupCustomer);

};

const createUser = (

attributes: UserAttributes,

onCreate: (user: User) => void

): User => {

user = User.create(attributes);

onCreate(user);

user.setupNotifications();

return user;

};

Using the terminology of defunctionalisation and refunctionalisation, this is an example of the latter. I still prefer this approach because it keeps admin-specific code in the createAdmin function and customer-specific code in the createCustomer function, however it does make it harder to grok what’s happening in the createUser function because the onCreate function could do absolutely anything. Admittedly, for such a small example, the refunctionalised approach is more convoluted, but as more types are added with their own idiosyncracies, I can see the type key approach devolving into a mess e.g:

const createUser = (

attributes: UserAttributes,

userType: 'admin' | 'user' | 'reporter'

setupArgs: SetupArgs

): User => {

user = User.create(attributes);

switch (userType) {

case 'admin':

setupAdmin(setupArgs, user)

case 'customer':

setupCustomer(setupArgs, user)

case 'reporter':

setupReporter(setupArgs, user)

}

user.setupNotifications();

return user;

};

How do you type SetupArgs here? Maybe different use cases require different setup args. Yes, we could use union narrowing, but in this situation I find using the onCreate callback is more sensible, because the call site can handle those arguments themselves (e.g. through a closure or partially applied function) and the typing problem goes away. When I say ‘call site’ I don’t mean ‘client’: we would be exporting createAdmin, createCustomer, etc to the client, and those functions can encapsulate any setup args stuff so that clients don’t need to worry about it. Of course, the caveats stated above in Switch statements need to live somewhere still apply here.

Another criticism around this example was that in the real world, admins are rarely fundamentally different from regular users: they typically just have elevated privileges. This is fair: the admin/customer example was pulled out of a hat without much forethought, but I think that it still serves to illustrate the broader point, contrived as it is.

Conclusion

It would be silly of me to conclude this post as self-assuredly as the original, so I’m going to simply summarise how I’ve personally revised my opinion on type keys. I find that type keys in general aren’t the devil, but that static type keys (i.e. type keys whose value you know at compile time) are closely related to the devil, and it’s worth seeing if the code is simplified by removing them. There are confounding factors like when you need to deal with orthogonal type keys, or when it makes sense for clients to use type keys, but in the wild I’ve found static type keys to be generally unnecessary and it doesn’t take long to see if a refactoring will simplify the code.

You could argue that saying ‘static type keys are a code smell’ is such a narrowly applicable statement that it’s almost not worth saying, but my original post was actually inspired from seeing static type keys needlessly introduced both at work and in my open source projects, so I think the statement still has merit.

Now, if refactoring to remove type keys results in obscured code that’s hard to follow, then screw your dependency diagrams! Just keep the type keys around and see if they start to cause headaches down the line. In a field as complex as programming, clarity is paramount and rarely can a simplified rule apply to all situations.

Hopefully you learnt as much reading this as I learnt writing it, but if you remain unimpressed by my conclusions, let me know in the comments and we’ll see whether my thesis can withstand a second round.

Until next time!

Shameless plug: I recently quit my job to co-found Subble, a web app that helps you manage your company's SaaS subscriptions. Your company is almost certainly wasting time and money on unused subscriptions and Subble can fix that. Check it out at subble.com