Code Smell of the Day: Type Keys

Note: On the back of some feedback I’ve created a follow-up of this post where I refine the thesis. I’ve left this post as-is for the sake of comparison

Say we have a function which creates a user, and handles some specific setup depending on whether that user is an admin or a customer:

const createUser = (attributes: UserAttributes, userType: 'admin' | 'customer'): User => {

user = User.create(attributes)

switch (userType) {

case 'admin':

setupAdmin(user)

case 'customer':

setupCustomer(user)

}

user.setupNotifications()

return user

}

...

// in some other file

const createAdmin = (attributes: UserAttributes): User => {

return createUser(attributes, 'admin')

}

...

// in yet another file

const createCustomer = (attributes: UserAttributes): User => {

return createUser(attributes, 'customer')

}

What do you notice about the userType argument? There are four things to note:

- its value is always known at compile time. We’re not receiving it as an parameter from an HTTP request or a value from the database.

- its expected to have one of a finite set of values i.e. it’s basically an enum.

- given that it’s basically an enum, its actual value is meaningless: it will never be written anywhere or compared to another variable’s value

- inside the function, the argument is only used in a switch-statement (if-statements count too) i.e. the value only affects the control flow of the function

When you have these four ingredients, you have a type key. Not ‘type’ as in static vs dynamic typing, but ‘type’ as in variant. It’s called a type key because it suggests that your function really has different variants and you want to key-in to a specific variant to get the behaviour you want.

This is an code smell because the only time you have different types is to satisfy different use cases, and different use cases always change at different rates. Maybe the setup process for admins hasn’t changed in a year but the process for customers changes monthly. Whenever two pieces of code need to change for different reasons, or at different rates, you must separate those pieces and minimise the dependencies between them. Otherwise, in order to understand how a customer is created, you need to wade through a bunch of irrelevant admin-related code, making any single use case impossible to understand without understanding all the others.

Let’s refactor this into something cleaner:

Step 1

Split the function and pull the type key argument into the function as a constant

const createAdmin = (attributes: UserAttributes): User => {

const userType = 'admin';

user = User.create(attributes);

switch (userType) {

case 'admin':

setupAdmin(user);

case 'customer':

setupCustomer(user); // this code path is never reached

}

user.setupNotifications();

return user;

};

const createCustomer = (attributes: UserAttributes): User => {

const userType = 'customer';

user = User.create(attributes);

switch (userType) {

case 'admin':

setupAdmin(user); // this code path is never reached

case 'customer':

setupCustomer(user);

}

user.setupNotifications();

return user;

};

Step 2

Clean up, removing any dead code paths

const createAdmin = (attributes: UserAttributes): User => {

user = User.create(attributes);

setupAdmin(user);

user.setupNotifications();

return user;

};

const createCustomer = (attributes: UserAttributes): User => {

user = User.create(attributes);

setupCustomer(user);

user.setupNotifications();

return user;

};

Step 3

Factor out any remaining overlapping code.

When Order Doesn’t Matter

You may find that certain operations are completely independent meaning you can shuffle the order of function calls. Let’s say that in this case setupNotifications() can be called before setupAdmin(user) and setupCustomer(user). Then we can group those together:

const createAdmin = (attributes: UserAttributes): User => {

user = User.create(attributes);

user.setupNotifications();

setupAdmin(user);

return user;

};

const createCustomer = (attributes: UserAttributes): User => {

user = User.create(attributes);

user.setupNotifications();

setupCustomer(user);

return user;

};

And then factor out:

// this function could be inlined if desired

const createAdmin = (attributes: UserAttributes): User => {

user = createUserWithNotifications(attributes);

setupAdmin(user);

return user;

};

// this function could be inlined if desired

const createCustomer = (attributes: UserAttributes): User => {

user = createUserWithNotifications(attributes);

setupCustomer(user);

return user;

};

const createUserWithNotifications = (attributes: UserAttributes): User => {

user = User.create(attributes);

user.setupNotifications();

return user;

};

When Order Does Matter

If the order was important, we could pass the in-between code as a callback:

// this function could be inlined if desired

const createAdmin = (attributes: UserAttributes): User => {

return createUser(attributes, setupAdmin);

};

// this function could be inlined if desired

const createCustomer = (attributes: UserAttributes): User => {

return createUser(attributes, setupCustomer);

};

const createUser = (

attributes: UserAttributes,

onCreate: (user: User) => void

): User => {

user = User.create(attributes);

onCreate(user);

user.setupNotifications();

return user;

};

And we’re done! We could go one step further by currying the result but for all intents and purposes this is pretty clean.

Why Is This Solution Better?

Our type key has magically disappeared and we no longer need to maintain it anymore. But that’s not the main reason we did this refactor. This is really about dependencies. Let’s compare the dependencies before and after our refactor:

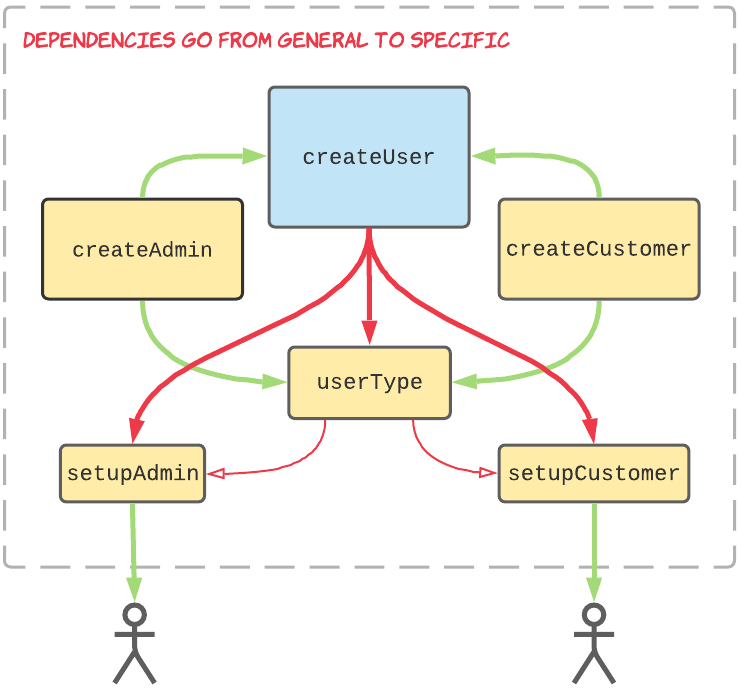

Before:

The red arrows represent a dependency from something general to something specific. These dependencies lead to bloated abstractions that are impossible to decipher. The mini-dependency arrows flowing from our userType type key are shrunken to represent the fact that a change in e.g. setupAdmin or setupCustomer may not require a change to userType, but adding/removing a user type will.

The little people represent reasons for change: perhaps all the changes to the setupAdmin function originate from feature requests from staff, but setupCustomer’s changes all originate from the product team. Whatever it is, the reasons for change are different.

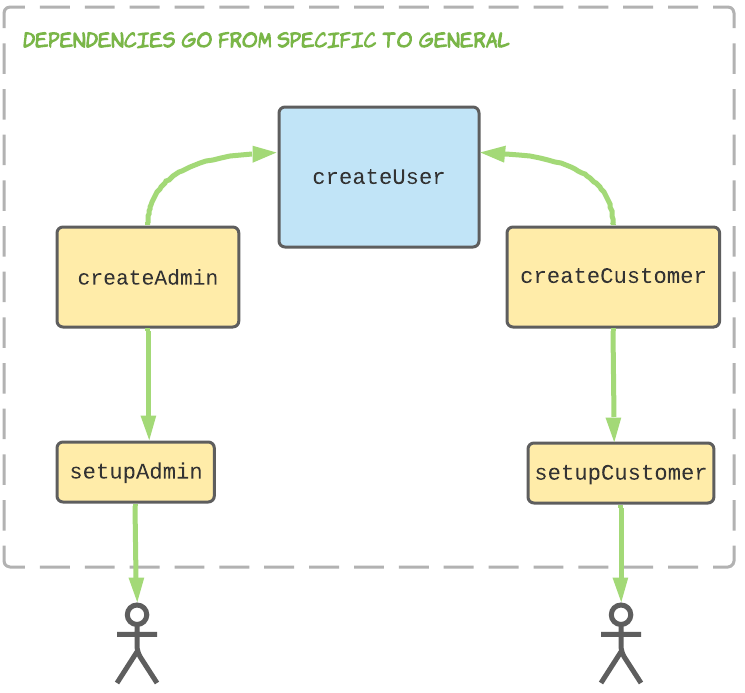

After:

Isn’t this nicer? There are fewer arrows flying around thanks to having userType out of the picture, but the important thing is that our createUser function is not dependent on our specific use cases, meaning that when changing a use case or adding a new use case (e.g. adding a ‘vendor’ user type) we don’t need to touch our createUser function. This is the basis of the Open-Close Principle: entities should be open for extention but closed for modification. This principle can only be satisfied when specific entities depend on general entities, not the other way around.

Note that instead of using callbacks we could have subclassed User to AdminUser and RegularUser, with each overriding the onCreate function. Regardless of which approach you take, you’ll get an identical dependency diagram!

Is It Always So Simple?

I originally titled this post Anti-pattern of the Day: Type Keys and asked readers to suggest counter-examples. As you can tell by the name change, some readers obliged! No matter how many heuristics and strategies you keep in your mental toolbox, there will always be situations that Just Suck for which there is no easy answer. Let’s take a look at one such example:

Flag arguments tacked onto the end of a function are a classic example of a type key (the only difference being that they’re capped to two possible values). Given their status as type keys, they should be eyed with suspicion, however Martin Fowler gives an example where there’s no obvious alternative:

public Booking book (Customer aCustomer, boolean isPremium) {

lorem().ipsum();

dolor();

if(isPremium) {

sitAmet();

}

consectetur();

if(isPremium) {

adipiscing().elit();

} else {

aenean();

vitaeTortor().mauris();

}

eu.adipiscing();

}

Granted, this function contains gobbledygook but it reflects a real world phenomenon: we read the type key several times within a function. Recalling that our goal is to remove the dependency from our general code (the book function) to our specific code (the premium/non-premium use cases), we need to find a refactor which satisfies this goal. Assuming order matters, we could once again employ callbacks:

// forgive the bastardised Java syntax

public Booking book (Customer aCustomer, afterDolor, afterConsectetur) {

lorem().ipsum();

dolor();

afterDolor()

consectetur();

afterConsectetur()

eu.adipiscing();

}

// equivalent of isPremium: true

booking = book(aCustomer, sitAmet, () => adipiscing().elit())

// equivalent of isPremium: false

booking = book(aCustomer, () => null, () => {

aenean();

vitaeTortor().mauris();

})

But the fact our two callbacks are named afterDolor() and afterConsectetur() should raise some eyebrows: we’re now requiring our specific code to know about the internal structure of our general code. This isn’t as bad as vice-versa, but note that the non-premium call to book needs to pass a no-op function for afterDolor() to satisfy the new interface, despite that callback only being relevant to the premium use-case. In effect we’ve swapped out an ugly mess of dependencies for an even uglier mess.

Subclassing Booking into PremiumBooking and RegularBooking would be just as bad: we’d still need afterDolor() and afterConsectetur() to be implemented by both subclasses.

Alternatively if we’re willing to tolerate some repetition we could split book in two like so:

public Booking bookPremium (Customer aCustomer) {

before();

sitAmet();

consectetur();

adipiscing().elit();

eu.adipiscing();

}

public Booking bookRegular (Customer aCustomer) {

before();

consectetur();

aenean();

vitaeTortor().mauris();

eu.adipiscing();

}

public before() {

lorem().ipsum();

dolor();

}

It would be easier to judge whether this was an improvement if the function names were in English, but it’s plain to see that no matter which approach we take, we’re sacrificing something, whether it’s DRYness, simplicity, or otherwise. When every option sucks in its own way, just pick the simplest and hide the weird stuff from the public API, as Fowler advises in the same article:

public Booking regularBook(Customer aCustomer) {

return hiddenBookImpl(aCustomer, false);

}

public Booking premiumBook(Customer aCustomer) {

return hiddenBookImpl(aCustomer, true);

}

private Booking hiddenBookImpl(Customer aCustomer, boolean isPremium) {...}

By encapsulating the type key, we ensure that future changes (for example adding a new booking type) won’t affect any client code.

Moral of the Story

If you can get rid of type keys, you should. If you can’t (without harming the code in some other way) you should hide them from the public API. Type keys are guilty until proven innocent, so if you’re writing or reviewing code that introduces a type key, spend the time thinking through how to satisfy the requirements without it, because, unchecked, type keys will bloat out your code and slow your development speed to a crawl.

Until next time!

Shameless plug (which appears on every blog post, not just this one, so don't think that I'm opportunistically posting this specific post just for the sake of doing this plug): I recently quit my job to co-found Subble, a web app that helps you manage your company's SaaS software licences. Your company is almost certainly wasting time and money on shadow IT and unused/overprovisioned licences and Subble can fix that. Check it out at subble.com