Go'ing Insane Part Three: Imperfect Interfaces

Standard preface: the purpose of this series is to put absolutely everything that bothers me about Go on the table to see who can relate. I’m not in the take-down business, I’m in the nitpicking business. So if you leave a comment saying ‘This is just nitpicking’ I will have no choice but to completely agree with you. I am not suggesting you will run into these issues on a daily basis, I am suggesting that when you do inevitably run into them, it will be frustrating. I don’t expect Go to change and I appreciate why people don’t want it to change.

In the last post we talked about privacy in Go. Here we’re talking about interfaces.

Go’s interfaces are implicitly implemented. To demonstrate:

type ICar interface {

Start()

}

type Car struct { // no need to explicitly say 'implements ICar'

sound string

}

func (c *Car) Start() { // because Car has a Start() function it implements ICar

fmt.Println(c.sound)

}

func main() {

// storing our concrete Car instance in a variable of type ICar

var c ICar = &Car{sound: "broom broom"}

c.Start() // prints 'broom broom'

}

This allows us to take a random struct from an external package which implements Start() and use it as an ICar. In effect, structs don’t need to know anything about the interfaces they implement. Or do they?

Chainable Methods

If I want to chain methods together, my ICar interface needs to specify ICar as the return type. But If the implementation of a chainable method returns, say, *Car, the compiler complains:

type ICar interface {

Start()

AppendSound(sound string) ICar // chainable method

}

...

func (c *Car) AppendSound(sound string) *Car {

c.sound = c.sound + " " + sound

return c

}

func main() {

// ERROR: cannot use &(Car literal) (value of type *Car) as ICar value in

// variable declaration: wrong type for method AppendSound

// (have func(sound string) *Car, want func(sound string) ICar)

var c ICar = &Car{sound: "broom"}

c.AppendSound("broom").Start()

}

To my knowledge, there is no good reason for this limitation: if I’m returning a *Car from AppendSound, and my interface wants me to return an ICar, that should be fine, right? Because *Car implements ICar! Nope, to satisfy this interface you’ll need to change your chainable methods to explicitly return ICar:

-func (c *Car) AppendSound(sound string) *Car {

+func (c *Car) AppendSound(sound string) ICar {

c.sound = c.sound + " " + sound

return c

}

The whole point of implicitly-implemented interfaces is that your structs don’t need to know about your interfaces, but with chainable methods they do.

Also worth noting here that if we had an error-bubbling operator like Rust’s ‘?’ operator, chaining methods which return errors would be much easier.

What If You Want To Be Explicit?

As you may have judged from the previous post about privacy, I like being explicit. If I want to mock out a struct in my tests, that means I need to:

- Create an interface with all of my struct’s methods

- Replace any references to the concrete type with references to the new interface

- Create a mock struct that also satisfies the interface

- Keep these three things (original struct, mock struct, interface) in sync

These two structs (the original and the mock) now live purely for the sake of satisfying that interface, yet that isn’t obvious from looking at the code. And if either struct is missing a method, you won’t get an error on the struct itself, you’ll get an error in some random part of the codebase where the struct is being assigned to that interface. I find this annoying, almost as annoying as the fact that a proposal for explicit implementation has already been rejected.

However, as a commenter stated, there is a workaround for this:

var _ ICar = (*Car)(nil)

This introduces a compile-time check that *Car implements ICar, without introducing any real runtime cost. Curiously, Effective Go states that we should only use this in the absence of other compile-time checks:

Don’t do this for every type that satisfies an interface, though. By convention, such declarations are only used when there are no static conversions already present in the code, which is a rare event.

First of all, shame on me for not having properly read Effective Go in advance. At any rate, companies like Uber share my perspective that sometimes being explicit about which interfaces are implemented at the point the struct is defined makes the code more expressive and easier to maintain, regardless of whether other compile-time checks exist in the code.

Slices of interface values

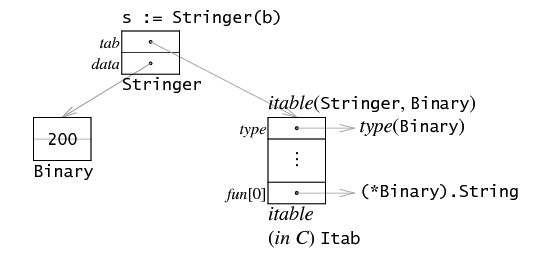

Interface values are fat pointers, meaning under the hood, they comprise a tuple of a concrete value and a concrete type.

When an interface method is called, Go looks at the concrete type to find the corresponding concrete method, and the concrete value is passed as the receiver. This all happens at runtime, which has important implications. For one, if you have a function that returns a slice of interface values…

func foo() []ICar {

// ...

}

… but then you actually try to return a slice of *Car’s, you’ll get an error:

func foo() []ICar {

// ERROR: cannot use ([]*Car literal) (value of type []*Car) as

// []ICar value in return statement

return []*Car{{sound: "broom"}, {sound: "brm"}}

}

This is because *Car’s are thin pointers but ICar’s are fat pointers, meaning they occupy different space at runtime. This requires a new slice to be constructed with interface values wrapping the concrete values. Go doesn’t want to hide this runtime cost from you, so it instead forces you to do the wrapping yourself (I don’t find this unreasonable, but I wonder if earlier design choices could have spared us from this conundrum entirely). If you know what concrete values you want ahead of time, wrapping isn’t so hard:

func foo() []ICar {

return []ICar{&Car{sound: "broom"}, &Car{sound: "brm"}}

}

But if you’re getting them from another function you need to add five lines of boilerplate.

func getCars() []*Car {

return []*Car{{sound: "broom"}, {sound: "brm"}}

}

func foo() []ICar {

cars := getCars()

icars := make([]ICar, 0, len(cars)) // 1

for _, car := range cars { // 2

icars = append(icars, ICar(car)) // 3

} // 4

return icars // 5

}

This drives me up the wall, no pun intended. Here’s an example from my open source project Lazygit (in fact that file contains pretty much every issue discussed in this post). This would be easier with generics but in their absence we’re condemned to writing big ugly blocks of boilerplate.

nil

As we discussed earlier, an interface value itself comprises a tuple of a concrete type and a concrete value, where the concrete value may be nil. But an interface value can itself also be nil. This gives us two kinds of nil we need to watch out for separately. For example:

func getICar() ICar {

return nil

}

func main() {

c := getICar()

c.Start() // PANIC: runtime error: invalid memory address or nil pointer dereference

}

Go has implicit nullability and does not warn you at compile time about possible nil pointer deferences; another place where discriminated unions would be nice, but let’s move on. We can prevent a panic here by checking if c is nil:

func getICar() ICar {

return nil

}

func main() {

c := getICar()

if c == nil {

fmt.Println("exiting")

return

}

c.Start()

}

So far so good, but what if our nil value originates from a function returning a *Car?

func getICar() ICar {

return getCar()

}

func getCar() *Car {

return nil

}

func main() {

c := getICar()

if c == nil {

fmt.Println("exiting")

return

}

c.Start()

}

You might expect the same result as before, but no. In this case we panic inside our Start() method:

func (c *Car) Start() {

fmt.Println(c.sound) // PANIC runtime error: invalid memory address or nil pointer dereference

}

If ever WTF? was an appropriate response, it’s now. So what happened?

getICarcallsgetCarwhich returnsnilgetICarwraps thatnilin the fat pointer[*Car, nil]and returns it- because

[*Car, nil] !== nil, we go on to callc.Start() - For some reason, Go allows calling methods on

nilreceivers called through an interface, so we go insideStart()and then panic when trying to accessc.sound

To get around this problem we can add an IsNil() method to the interface, with every implementing struct returning whether the receiver is nil:

type ICar interface {

Start()

AppendSound(sound string) ICar

IsNil() bool

}

...

func (c *Car) IsNil() bool {

return c == nil

}

Then when doing a nil check, you then need to check for both c == nil (for when the interface value is itself nil) and c.IsNil() (for when the concrete value is nil):

func main() {

c := getICar()

if c == nil || c.IsNil() {

fmt.Println("exiting")

return

}

c.Start()

}

Not ideal: extracting a concrete-typed function from an interface-typed function, a refactor that should have no impact on runtime behaviour, can crash your app. Now you’ll need to remember to use c == nil || c.IsNil() whenever doing nil checks with interface values.

Maybe there’s some pattern to get around this problem that I’m not aware of, but the fact it can catch newbies by surprise runs contrary to the language’s emphasis on being newbie-friendly.

There are a couple of ways the language could solve this: you could have == nil handle fat pointers with nil concrete values, or you could have functions which return an interface value use a fat pointer when returning nil explicitly, so that at least you have consistency. I’m also interested to know whether fat pointers really are required at runtime, or if there is some way to get around that.

Conclusion

What do all of these examples have in common? They all show that introducing an interface where previously you only dealt with concrete values is not as simple as find-and-replace. Implicit implementation is not possible in the case of chainable methods, chunks of boilerplate must be added when dealing with slices, and subtle bugs appear when nil values are involved.

Why does this matter? Because interfaces are Go’s only way to support polymorphism. Generics (i.e. parametric polymorphism) will render much of this post moot, but until they arrive, substituting structs for interfaces means contending with some or all of the above problems (or maybe none, who knows).

These shortcomings feel more like the result of poorly-conceived design choices than sensible tradeoffs. I’m not a programming language designer myself (EDIT: actually yes I am now, but definitely not an authority) so for all I know these are all necessary evils, but I can say that as an end-user it’s not a great experience.

Next up: Mandatory Mutation.

After writing this blog series, I decided I needed to balance out all the negativity of the posts with something positive, so I made a joke programming language to air my grievances with a comedic spin. Feel free to check it out: OK?. If you’re intimately familiar with Go’s history you might spot some easter eggs

Addendum

In the context of testing, something I’d like to see is the ability to derive an interface from a struct like so.

derive type ICar interface from *Car // hypothetical Go syntax

This means you don’t need to waste time manually keeping ICar and *Car in-sync, and it signals to the reader that ICar only exists for the sake of testing via a mock. A proposal for this has been rejected and understandably: Inversion Of Control says concrete things should depend on abstract things and not vice-versa. But damn, does anybody else wish this was a feature? Right now I’m using the code generation tool ifacemaker to generate the interface from the original struct, which then feeds into another code generation tool for making the mock, counterfeiter. It would be nice to remove one step from that process, especially given that ifacemaker has some bugs at the moment.

Go'ing Insane Series

Post 4 of 6.

Shameless plug (which appears on every blog post, not just this one, so don't think that I'm opportunistically posting this specific post just for the sake of doing this plug): I recently quit my job to co-found Subble, a web app that helps you manage your company's SaaS software licences. Your company is almost certainly wasting time and money on shadow IT and unused/overprovisioned licences and Subble can fix that. Check it out at subble.com