True Code Reuse In Go

If you google ‘Code Reuse In Go’ and read through the first two pages of results, you’ll see many of the same concepts come up:

- Composition > Class Inheritance

- Go lacks class inheritance

- Go achieves polymorphism through interfaces

- Struct embedding makes this easier

We can all agree that class inheritance is problematic because it can lead to rigid class hierarchies and often it makes more sense to model relationships between objects as has-a (composition) rather than is-a (inheritance). So it’s suspicious that the Gang Of Four whose design patterns book popularised the phrase ‘Favour composition over class inheritance’ went on to fill that book with design patterns that almost all involved class inheritance.

Something’s going on. I feel a discussion on what’s so bad about class inheritance could benefit from spending more time asking: what’s so good about class inheritance, such that its absence can feel so stunting to Go newcomers? Turns out it has nothing to do with class hierarchies.

Reading through the typical blog post on the topic, you’ll be told that the closest relative to class inheritance in Go is struct embedding. The idea is that you can wrap an interface in your struct and in doing so, you can forward method calls to that embedded struct. To give a classic (and infamous) example, your car struct can embed an Engine to handle engine-ey stuff:

type MyCar struct {

*Engine

}

type Engine struct{}

func (e *Engine) Start() {

fmt.Print("broom")

}

func main() {

car := MyCar{Engine: &Engine{}}

car.Start() // prints 'broom'

}

So much for class inheritance! Go has everything we need. Or does it? Note that above I said that with struct embedding you can forward methods to embedded structs. Forwarding is not the same as delegating.

As stated in Effective Go:

There’s an important way in which embedding differs from subclassing. When we embed a type, the methods of that type become methods of the outer type, but when they are invoked the receiver of the method is the inner type, not the outer one.

Our engine has no access to the other fields in our car: it only has access to its own fields. When you call car.Start() it’s just syntactic sugar for car.Engine.Start().

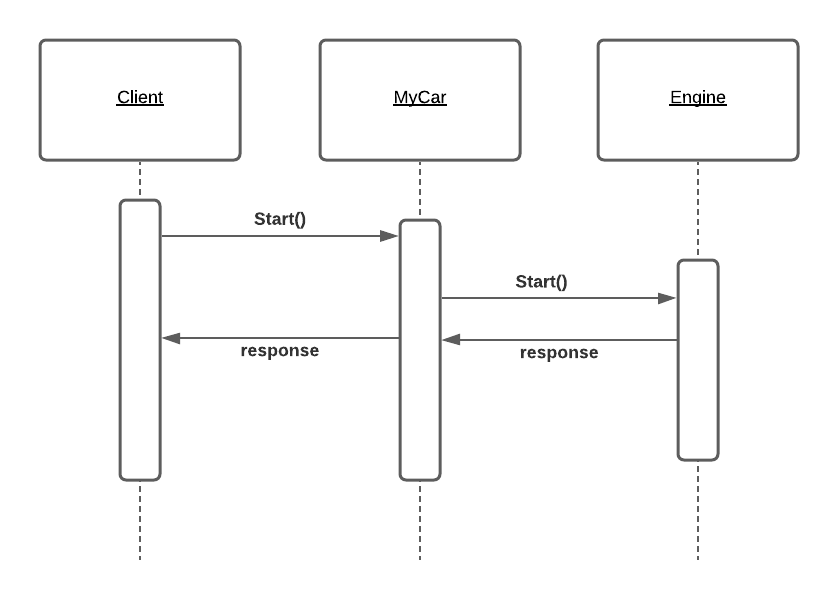

Here’s a diagram to demonstrate. Note that the only way our engine can communicate with our car is by returning from a method call: it can’t invoke any methods on our car. That is, method-call arrows can only go forward in one direction (hence the name forwarding).

So, if I add a StartSound() method to my MyCar struct, I can’t make use of that in my Engine struct:

type MyCar struct {

*Engine

}

type Engine struct{}

func (c *MyCar) StartSound() string {

return "broom"

}

func (e *Engine) Start() {

// ERROR: e.StartSound undefined (type *Engine has no field or method StartSound)

fmt.Print(e.StartSound())

}

func main() {

car := MyCar{Engine: &Engine{}}

car.Start()

}

Damn! With delegation, the receiver in our embedded struct Engine could actually point to the embedding struct MyCar. Let’s look at a similarly contrived example where delegation is called for.

Say I had various structs representing people, each with a GetName() method:

type HasName interface {

GetName() string

}

type SimpleNamedPerson struct {

name string

}

func (p *SimpleNamedPerson) GetName() string {

return p.name

}

type ComplexNamedPerson struct {

firstname string

lastname string

}

func (p *ComplexNamedPerson) GetName() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("%s %s", p.firstname, p.lastname)

}

I want to be able to greet these people by calling .Greet() on them. That is, I want to find a way to have both SimpleNamedPerson and ComplexNamedPerson implement the Greeter interface.

type Greeter interface {

Greet()

}

We could introduce a greeter function like so:

func GreetInEnglish(p HasName) {

fmt.Printf("Hello %s\n", p.GetName())

}

This is what’s typically recommended in blog posts that talk about type embedding: you enable polymorphism by having a function take an instance of an interface and then make use of that instance’s methods. But how does this help us satisfy the Greet interface? We could define the Greet() function in our struct and call the language-specific greet function from within:

func (p *SimpleNamedPerson) Greet() {

GreetInEnglish(p)

}

func (p *ComplexNamedPerson) Greet() {

GreetInEnglish(p)

}

But this isn’t very extensible. If we promote our ‘Greeter’ interface to ‘Speaker’ and add more methods to it (e.g. SayGoodbye()), we’ll need to go and add boilerplate to each of our structs to call the SayGoodbyeInEnglish() method).

type Speaker interface {

Greet()

SayGoodbye()

}

...

func (p *SimpleNamedPerson) SayGoodbye() {

SayGoodbyeInEnglish(p)

}

func (p *ComplexNamedPerson) SayGoodbye() {

SayGoodbyeInEnglish(p)

}

Can struct embedding save us? It actually can, with a little extra effort. Let’s create an ‘EnglishSpeaker’ struct which itself embeds an instance of the HasName interface.

type EnglishSpeaker struct {

HasName

}

func (s *EnglishSpeaker) Greet() {

fmt.Printf("Hello %s\n", s.GetName())

}

func (s *EnglishSpeaker) SayGoodbye() {

fmt.Printf("Goodbye %s\n", s.GetName())

}

func NewEnglishSpeaker(person HasName) Speaker {

return &EnglishSpeaker{HasName: person}

}

And then we tweak our person struct to now embed the EnglishSpeaker.

type SimpleNamedPerson struct {

name string

Speaker

}

func NewSimpleNamedPerson(name string) *SimpleNamedPerson {

p := &SimpleNamedPerson{name: name}

p.Speaker = NewEnglishSpeaker(p)

return p

}

type ComplexNamedPerson struct {

firstname string

lastname string

Speaker

}

func NewComplexNamedPerson(firstname string, lastname string) *ComplexNamedPerson {

p := &ComplexNamedPerson{firstname: firstname, lastname: lastname}

p.Speaker = NewEnglishSpeaker(p)

return p

}

func main() {

person := NewSimpleNamedPerson("Jesse Duffield")

fmt.Println(person.GetName()) // prints "Jesse Duffield"

person.Greet() // prints "Hello Jesse Duffield"

person.SayGoodbye() // prints "Goodbye Jesse Duffield"

otherPerson := NewComplexNamedPerson("Jesse", "Duffield")

fmt.Println(otherPerson.GetName()) // prints "Jesse Duffield"

otherPerson.Greet() // prints "Hello Jesse Duffield"

otherPerson.SayGoodbye() // prints "Goodbye Jesse Duffield"

}

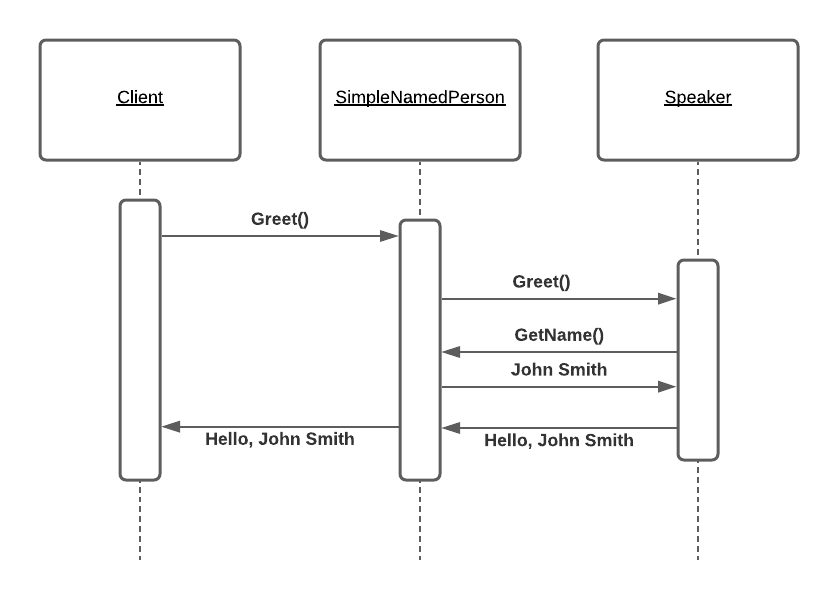

Here’s a diagram of what’s happening:

Pretty cool! But what if we don’t just have English speakers? We can create a FrenchSpeaker struct that satisfies the Speaker interface.

type FrenchSpeaker struct {

HasName

}

func (s *FrenchSpeaker) Greet() {

fmt.Printf("Bonjour %s\n", s.GetName())

}

func (s *FrenchSpeaker) SayGoodbye() {

fmt.Printf("Au revoir %s\n", s.GetName())

}

func NewFrenchSpeaker(person HasName) Speaker {

return &FrenchSpeaker{HasName: person}

}

And we can inject our speaker into our person constructor like so:

func NewSimpleNamedPerson(name string, getSpeaker func(HasName) Speaker) *simpleNamedPerson {

p := &simpleNamedPerson{name: name}

p.Speaker = getSpeaker(p)

return p

}

...

person := NewSimpleNamedPerson("Jesse Duffield", NewFrenchSpeaker)

fmt.Println(person.GetName()) // prints "Jesse Duffield"

person.Greet() // prints "Bonjour Jesse Duffield"

person.SayGoodbye() // prints "Au revoir Jesse Duffield"

Mission accomplished: You can now:

- add a new struct implementing the

Speakerinterface to support a new language - add a new method to the

Speakerinterface, and implement it in each language struct, to have it automatically come through in our person structs - add a new person struct implementing

HasNameand give it speaking abilities by embedding aSpeaker

This is the kind of code-reuse I was looking for when I started using Go. Yes, using vanilla interfaces and struct embedding is technically a form of code reuse, but so is the existence of functions themselves. When somebody googles code reuse mechanisms, they typically have something more powerful in mind, and I’d say this pattern hits the spot.

The Go Trait Pattern

I haven’t come across any online posts talking about this pattern in Go (I’m sure they exist) so until somebody tells me the real name, I’m calling this the Go Trait Pattern. Adding ‘delegation’ to the name wouldn’t suit given how most people conflate delegation with forwarding, and given how closely our embedded struct in this pattern resemble’s Rust’s traits, I think the name fits. If your trait contains its own state, you could call it a mixin, but that’s up to you. With this pattern, the trait (i.e. the embedded struct: EnglishSpeaker and FrenchSpeaker) defines an interface that the embedder (SimpleNamedPerson, ComplexNamedPerson) must satisfy, and the deal is that if the embedding struct can satisfy that interface, the trait will reward it with extra functionality. Unlike with forwarding, here the embedded struct can actually make use of logic defined in the embedding struct.

In the broader context of programming, this pattern is nothing new. It’s just classic delegation. In 1994, Grady Brooch defined delegation like so:

Delegation is a way to make composition as powerful for reuse as inheritance. In delegation, two objects are involved in handling a request: a receiving object delegates operations to its delegate. This is analogous to subclasses deferring requests to parent classes. But with inheritance, an inherited operation can always refer to the receiving object through the this member variable in C++ and self in Smalltalk. To achieve the same effect with delegation, the receiver passes itself to the delegate to let the delegated operation refer to the receiver.

You might be thinking: doesn’t this just re-introduce the fragile base-class problem? Not so! Our trait decides what interface the embedding struct must satisfy, and can only interact with it through that interface. Likewise, the embedding struct can override methods on the trait, but doing so won’t actually affect the trait’s behaviour. For example, if SimpleNamedPerson defines their own Greet() method, it will simply shadow the trait’s own Greet() method.

The ability for method invocations to go in both directions is the secret sauce that most Go newcomers are looking for when they ask about inheritance, and struct embedding with basic forwarding does not fill the void, but the trait pattern can.

Considerations

There are some things worth keeping in mind. Firstly, Go lacks covariance, meaning the general rule that functions should accept interface values and return concrete types doesn’t work here. NewEnglishSpeaker needs to return Speaker if it is to be passed as the makeSpeaker argument. This isn’t a huge deal: you can always just make a separate function for that. This assumes you actually need to inject the trait can’t can’t invoke it directly.

Another thing to note is that our person constructor is a little weird:

func NewSimpleNamedPerson(name string, makeSpeaker func(HasName) Speaker) *SimpleNamedPerson {

p := &SimpleNamedPerson{name: name}

p.Speaker = makeSpeaker(p)

return p

}

We need to first partially build the struct, then assign the speaker field to finish it off. Whenever you see this kind of code, it means there’s a circular dependency. This isn’t a problem for the garbage collector: Go uses a mark-and-sweep algorithm so it handles circular dependencies just fine. But it does mean you need to ensure not to call .Greet() or .SayGoodBye() from within GetName(), as doing so will result in an infinite loop. If this concerns you, you could forget about the double-embed approach and instead embed your person struct inside the Speaker and call it a day, but that will lock you in to the HasName and Speaker interface: you won’t have access to any other methods defined on your person struct. Alternatively, you could extract the part of the struct that implements HasName into its own struct and pass that to your Speaker trait. If you’ve got multiple traits and each requires a different combination of fields/methods, you could use an auxilliary struct to hold all of those and have your outer struct hook everything up. Much more boilerplate, but it removes the circular dependency. I’ll admit I haven’t put much thought into these alternatives: they warrant more exploration.

One final implication of the trait pattern is that when I call person.Greet() we’re using dynamic dispatch twice: that is, we call Greet() on our trait interface which in turn calls GetName() on our embedding struct, also through an interface. This means we have to traverse a couple of pointers to get the functions we want. But, in my opinion, it’s worth the cost, and Go provides no alternative that I know of.

So there you have it, the trait pattern. There are some hairy parts due to the language’s lack of first-class traits, but it enables richer polymorphism. Do you need to use it? No. Will it cause more problems than it solves? I have no idea: I only just thought of it and plan to start battle-testing it in my own Go side-projects. But you might come across a situation where it proves useful. My typical post contains some embarrassing oversight or error, so I look forward to finding out what it is this time. At any rate, see you in the next post!

Addendum

Here are the posts I read through in the first two pages of googling ‘Code Reuse in Go’: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

In this post I’ve contended that the good thing about inheritance is two-way method invocation, but if you want to learn much more about it’s various features, and how they can be ported in a non-inheritancey way, read this.

Shameless plug (which appears on every blog post, not just this one, so don't think that I'm opportunistically posting this specific post just for the sake of doing this plug): I recently quit my job to co-found Subble, a web app that helps you manage your company's SaaS software licences. Your company is almost certainly wasting time and money on shadow IT and unused/overprovisioned licences and Subble can fix that. Check it out at subble.com