Stop selling me trichotomies!

If you’ve ever taken a class in persuasive language, or if you’ve ever joined a debating club, or if you’ve ever listened to a politician’s speech, you’ll know that humans love their triplets:

- I came, I saw, I conquered

- Unit, God, Country

- The Father, The Son, and the Holy Spirit

- Hook, Line, Sinker

- Live, Laugh, Love

- Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness

Why does the number three hold such a special place in the human heart?

Why do humans love triplets?

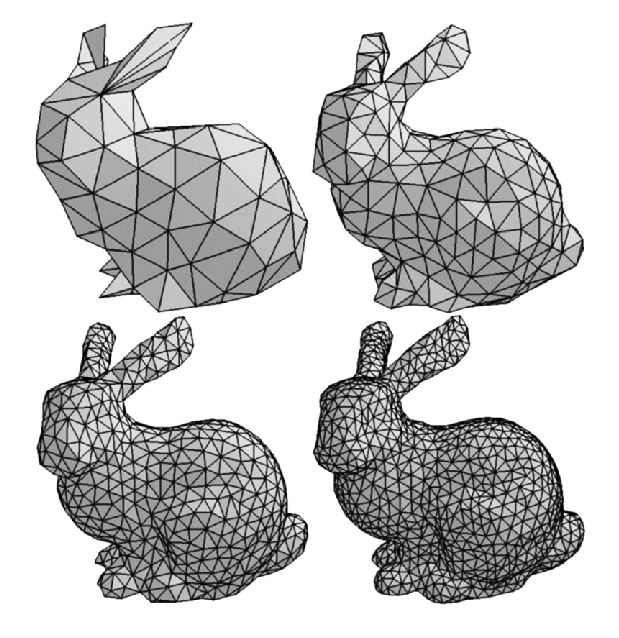

I believe our love of triplets derives from geometry: with two points you can only form a line in one-dimension (boring and useless), but with three points you get promoted into the second dimension with a triangle (exciting, and powerful). You might think that structures with four points (like squares) are the backbone of 3D environments. Nope! four points is overkill; zoom into any computer-generated 3D environment and you’ll find it’s all composed of little triangles.

Triangles are central to structural engineering: we use trusses (triangular structures) in our tables, bridges, and roofs to prevent them from collapsing under force. MythBusters proclaimed that triangles are the strongest shape.

Okay, so triangles are important in our three-dimensional world. Why, then, are humans so hypnotised by triplets in spoken language?

The human psyche is heavily influenced by geometry after spending millions of years of evolution hurling spears at animals for our next meal. Even 3.7 billion years prior when we were amoeba, uselessly floating around in the ocean with impunity, we were still interacting with things in physical space. Comparatively, we’ve only had spoken language for about 2 million years, i.e. 0.05% of our evolutionary history. After all that time spent thinking in geometric terms, it’s no wonder we try so hard nowadays to represent abstract concepts visually to help us make sense of them, hence the common phrase ‘ummm… perhaps you could explain with a diagram?’.

Geometric metaphors abound in our everyday life. When the news reporter informs you that that Nvidia stock went up, the stock price didn’t actually go up, instead the stock price increased in value. You’re probably thinking ‘what’s the difference?!’ and that’s because you’ve spent so long associating the word ‘increase’ with ‘up’ and ‘decrease’ with ‘down’ that you’ve forgotten that it’s an arbitrary association which we only created in the first place to help us visualise numbers in our geometry-obsessed heads.

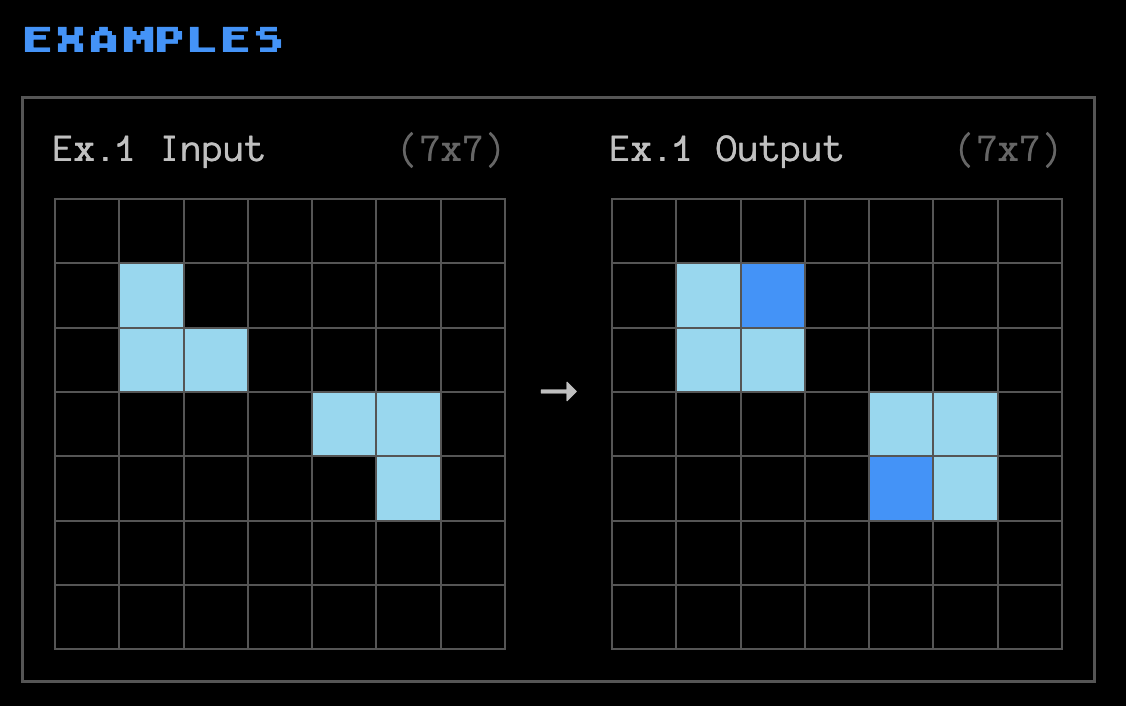

It should be no surprise then that although LLMs (Large Language Models, like ChatGPT) can outperform many humans on medical and legal tests, the one test where they hilariously under-perform compared to humans is the ARC test which is entirely composed of… wait for it… basic geometric puzzles:

Which brings us back to triplets. When you hear a triplet like ‘Mind, Body, Spirit’, it feels stable and sound, because humans have a deep intuition that triangles comprised of three interconnected concepts are just as strong as the triangles that hold our bridges together in the real world.

But is this intuition right? Are our triplets actually meaningful or are they just arbitrary?

Arbirary trichotomies

I want to focus on a specific kind of triplet: a trichotomy, which means a breakdown of something into three parts (compared to a dichotomy which involves only two parts).

What do we want from our trichotomies? Here’s what I want:

- Each part is mutually exclusive, so no overlap

- The whole is collectively exhaustive i.e. there’s no missing parts1

- The division is globally true (not just in one specific case)

- It doesn’t slice up a continuum

If you can’t satisfy all those criteria, I will declare your trichotomy as arbitrary. Otherwise, I’ll consider it fundamental.

Let’s see how some well known trichotomies fare against our criteria.

States of matter

In school I was told there are three states of matter: solid, liquid, and gas. Oh wait… except there’s a fourth one called ‘plasma’, and if you look hard enough you’ll also encounter ‘Bose–Einstein condensates’ and ‘Fermionic condensates’. This trichotomy is not collectively exhaustive, so I’m hereby declaring it arbitrary.

Branches of government

Let’s try another one: the three branches of government: legislative (writes laws), executive (enforces laws) and judiciary (interpret laws). There’s no need to stop at three: we could include The People (votes representatives into power) and The Press (holds other branches accountable) but even if we believe the original trichotomy makes sense, notice that it’s by design! There are many countries that make no attempt to separate the executive from the legislative, and there are some countries with no separation at all. So, not collectively exhaustive, and not globally true. Arbitrary.

Mind, Body, Spirit

To use an earlier example, what about Mind, Body, and Spirit? Well, the atheists in the room take issue with the inclusion of ‘Spirit’, and the sociologists are wondering why ‘Community’ wasn’t included. Arbitrary.

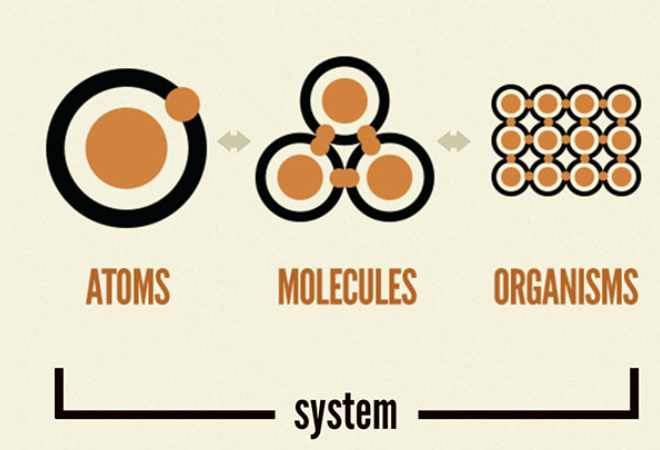

UX components

Let’s bring it a little closer to home. I remember at a previous company where for a time, Brad Frost’s Atomic Design was all the rage. Atomic Design is a conceptual framework for organising system UX components into three elements: atoms, molecules and organisms. I remember disputes about whether a given component was an atom or a molecule and in the end it just didn’t matter (The map is not the territory!). The level of abstraction in UX components (like all things) is a continuum, so Atomic Design fails the continuum test and is hereby dubbed arbitrary. Atomic Design has since been revised to include ‘ions’ and ‘quarks’ so it also fails the collectively-exhaustive test.

Fundamental trichotomies

Are there any trichotomies that actually hold water? Yes! Some examples

- Time: Past, present, and future

- The outcome of a game: Win, lose, draw

- The three horns of a triceratops

What do these examples have in common? They each just break down into dichotomies. With time you’ve got the dichotomy of past vs future, with an extra category for where the meet in the middle (the present). You could argue time is a continuum so past/present/future must be an arbitrary trichotomy, but the fact that the present isn’t really a slice of time so much as it is a point in time means that trichotomy is off the hook. With the horns of a triceratops you’re asking two yes/no questions: is the horn on the brow or the nose? And if it’s on the brow, is the horn on the left or the right? With win, lose, draw the two yes/no questions are ‘did one of us beat the other?’ and ‘if so, who?’.

What’s special about dichotomies? It’s easy to state a dichotomy whose parts are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive just by saying one half is X and the other half is not-X. So if you combine multiple non-arbitrary dichotomies, you’re likely to end up with a trichotomy (or quadrichotomy, etc) which is itself not arbitrary.

My ultimate contention is this: any trichotomy which doesn’t break down into one or two dichotomies is almost certainly arbitrary and some guy just coined it years ago and nobody has questioned it since.

Let’s test this contention against some more examples

More trichotomy examples

Freud’s id, ego, and super-ego

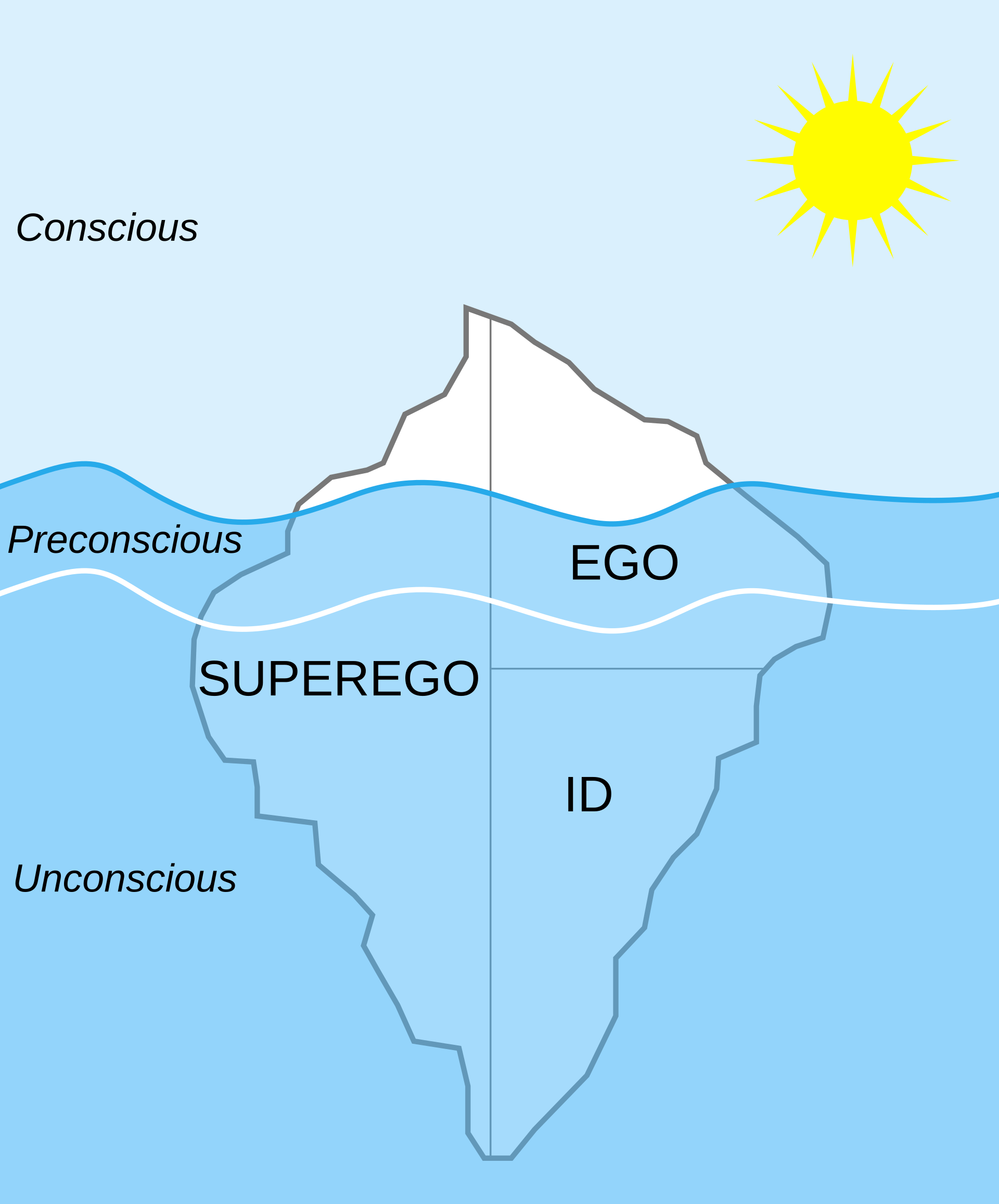

Straight from the wikipedia page, look at this diagram and tell me that’s not two dichotomies! Although I’d slice it the other way: seems like the two questions are ‘are you bottom-up or top-down?’ (with ego being top-down) and then ‘are you positively or negatively valenced?’ (with id being positively valenced and super-ego being negatively valenced)

Freud’s impulsive trichotomising doesn’t stop there: you’ll notice he’s also got unconscious, preconcious, and conscious in the above diagram, but that fails the continuum test. So I’d class that as arbitrary.

Plato’s tripartite soul

Plato partitions man’s soul into three parts: The Man (rationality), The Lion (pride, passion, etc), and The Beast (base desires).

You could argue this is two dichotomies (rational vs emotional, then noble vs ignoble emotions). But the lion/beast dichotomy seems sufficiently fuzzy that I think this fails the collectively-exhaustive test: if Plato had added a fourth part like ‘The Child’ (childlike inspiration/creativity), ‘The Witness’ (base consciousness), I don’t think anybody would have objected.

Hegel’s dialectic

The idea here is that there’s thesis (some idea), antithesis (some conflicting idea), and synthesis (some resolution of the two ideas). This has a similar structure to past, present, future in that it’s really just a dichotomy (thesis and antithesis) and a separate category for how they interact. So… this sounds fundamental to me. For the record, the dialectic has always struck me as being too general to be of any conceptual use to me, but there are lots of smart people who see everything through the dialectical lens so what do I know?

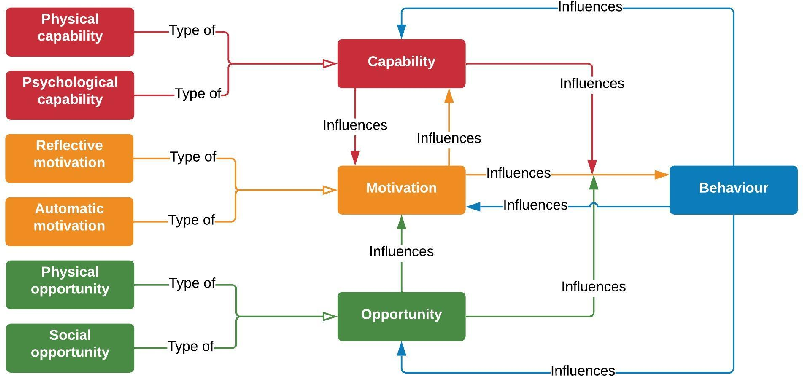

The COM-B model of behavioural change

I happen to know that this gets used in physio-therapy research. The idea is that behaviour is influenced by three factors: capability, motivation, and opportunity. I think this is a uniquely bad trichotomy: not only do they all interact in convoluted aways, but for very simple situations it’s not clear how to categorise things: if somebody is clinically depressed and can’t get out of bed, is that a motivation issue or a capability issue? If somebody loses their job and can’t afford a treatment, is that an opportunity issue or a capability issue? This fails both the mutually-exclusive and collectively-exhaustive tests, so I deem it arbitrary.

The Christian Trinity

Per my Christian upbringing and latent fear of God, I hesitate to openly describe the Christian Trinity of The Father, The Son, and The Holy Spirit as arbitrary. Instead I’ll simply talk about an entirely separate partitioning of a monotheistic deity into distinct aspects: the Faith of The Seven from GRRM’s Game of Thrones series.

The Seven comprises The Father, The Mother, The Smith, The Warrior, The Maiden, The Crone, and The Stranger. At a whopping seven aspects, you’d be forgiven for thinking there’s just no way that this partitioning passes the mutual exclusion test or the collective exhaustion test, but the ‘Song of the Seven’ does a good job of making it feel fundamental and cohesive:

The Father’s face is stern and strong, he sits and judges right from wrong. He weighs our lives, the short and long, and loves the little children.

The Mother gives the gift of life, and watches over every wife. Her gentle smile ends all strife, and she loves her little children.

The Warrior stands before the foe, protecting us where e’er we go. With sword and shield and spear and bow, he guards the little children.

The Crone is very wise and old, and sees our fates as they unfold. She lifts her lamp of shining gold to lead the little children.

The Smith, he labors day and night, to put the world of men to right. With hammer, plow, and fire bright, he builds for little children.

The Maiden dances through the sky, she lives in every lover’s sigh. Her smiles teach the birds to fly, and gives dreams to little children.

The Seven Gods who made us all, are listening if we should call. So close your eyes, you shall not fall, they see you, little children. Just close your eyes, you shall not fall, they see you, little children.

Of course, in modern times I think it’s missing the eighth fundamental entity: The Programmer:

The Programmer works into the night on a laptop screen that burns so bright he ships the code that runs your site and inspires little children.

So although I can totally get around the Faith of the Seven, it fails the collectively-exhaustive test and regrettably must be deemed arbitrary.

Conclusion

To recap: my claim is that trichotomies which are not composed of one or two dichotomies are almost certainly arbitrary, and I think with the above examples that’s been demonstrated.

To be clear, there’s nothing wrong with an arbitrary trichotomy! Many trichotomies are useful despite being arbitrary: for example, the Hungry, Humble, Smart trifecta is a great heuristic when hiring talent. The mistake to avoid is presupposing that an arbitrary trichotomy is in fact fundamental, and then wasting time arguing about which slice an edge-case belongs to.

In closing, there are three kinds of people in this world: those who have never heard the word ‘trichotomy’ before (which includes myself before writing this post), those who have heard the word and who assume trichotomies are all fundamental, and those who assume trichotomies are arbitrary until proven fundamental. If you train yourself to be the third kind of person, I guarantee that you will become happy, healthy, and whole.

If you can think of a fundamental trichotomy which is not composed of dichotomies, let me know!

Appendix: Quadrichotomies

I’ve confined this post to only talk about trichotomies but it only gets worse when you think about partitions of four or more elements. The example that inspired this post was actually a quadrichotomy on Eric Weinstein’s podcast The Portal, with guest Agnes Callard. Eric suggested that to resolve a debate about truth, you could posit the following four elements: truth, meaning, fitness, and grace. Agnes responded:

Okay, so So first of all, like, I think anytime you divide things and like philosophers disagree about this, like some philosophers are fine with a certain thing I’m about to describe, but like, I think you can’t just divide things into four things. You’re like, here are the four things. These are the things I found. I’m like, well, what’s the principle of division? Like? Is that just something you made up? Like, what if we come up with a fifth one? So I want to understand it. I want to understand sort of how the whole is articulated into those things. Until I understand that I just don’t feel like I’ve, I’ve understood anything.

I wonder what agnes thinks of my four criteria for a trichotomy to be fundmental: perhaps she thinks that is itself arbitrary!

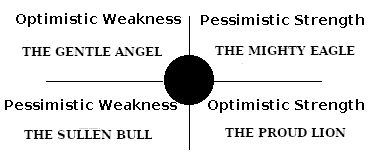

There are plenty of quadrichotomies that just encode two dichotomies: one that comes to mind is the example from Prometheus Rising that explains the four temperaments: The Eagle (I’m okay, you’re not okay), The Lion (I’m okay, you’re okay), The Bull (I’m not okay, you’re not okay) and The Angel (I’m not okay, you’re okay).

Footnotes

Shameless plug (which appears on every blog post, not just this one, so don't think that I'm opportunistically posting this specific post just for the sake of doing this plug): I recently quit my job to co-found Subble, a web app that helps you manage your company's SaaS software licences. Your company is almost certainly wasting time and money on shadow IT and unused/overprovisioned licences and Subble can fix that. Check it out at subble.com