React Bedtime Stories Episode 1: The Form Of Death

What you are about to hear is a tale full of danger, excitement, and personal growth. You will come across the evil Dragon Of New Requirements, and the Serpent Of Typescript’s Lacking Type Inference. Polymorphism spells will be cast, Abstractions will rise and fall, and chests of various colours will explode. Although this tale requires no advanced knowledge, it will require courage and persistence, because it is a terrifying tale of twists and turns that, in real life, spanned weeks.

The story begins with a simple quest: we must create a form. What kind of form? The kind of form that lets you build URLs of various kinds to embed in an email. For example, you could use this form to build a web URL which would just require you to type that URL into an input box. Or maybe you want to create a telephone URL which also uses an input box but prepends the value with tel: upon save. Or maybe you want to create a mailto: URL which contains an email address, subject, and body in the query string so that upon clicking this link your email client pops up with a pre-composed email ready to send. Or, finally, maybe you want to link to a URL in a set of known landing pages provided by an API, via a select box.

The quest sounds simple enough! We just need a form which lets you pick which link type you want to build, and then we need to display a tab which lets you enter in the details for that URL. There is one small caveat: the button to save the url can’t be rendered by the tabs themselves, because we already have a modal component we use to render these kinds of forms, and that component renders the buttons itself. That means that the parent form component will need to know whether the current value is valid or not.

In the end we should have something like this:

Okay, let’s go.

Chapter 1: The Journey Begins (code sandbox)

For now we’ll focus on just the email and telephone tabs, and we can add the other tabs when we’re happy with our direction.

For each tab we’ll need a function which takes the current url and parses it to obtain the content of that tab’s inputs:

const telephoneFromUrl = (url: string) => {

return url.replace('tel:', '');

};

const emailFromUrl = (url: string) => {

let parsedUrl;

try {

parsedUrl = new URL(url);

} catch (e) {

return { email: '', subject: '', body: '' };

}

const email = parsedUrl.pathname;

const params = parsedUrl.searchParams;

const subject = params.get('subject') || '';

const body = params.get('body') || '';

return { email, subject, body };

};

We’ll also need functions for going in the other direction: returning a url from our tab’s inputs:

const urlFromTelephone = (telephone: string) => {

return `tel:${telephone}`;

};

const urlFromEmail = ({

email,

subject,

body,

}: {

email: string;

subject: string;

body: string;

}) => {

const query = { subject, body };

const queryString = new URLSearchParams(query).toString();

return `mailto:${email}?${queryString}`;

};

Finally, we’ll also want some functions for telling us whether a given url is valid. We’ll make use of telephoneFromUrl and emailFromUrl for these given that it will be easier than trying to validate the url directly. For telephones we just want them to contain numbers (but also permit things like brackets) and for email we just want the email address to be a real email address. Because we’re lazy we’ll just ensure there’s an ‘@’ symbol in the email url for now.

const isTelephoneUrlValid = (url: string) => {

return !!telephoneFromUrl(url).match(/^[\d +().x]+$/);

};

const isEmailUrlValid = (url: string) => {

const emailParts = emailFromUrl(url);

// TODO: real validation

return !!emailParts.email.includes('@');

};

Okay with these functions we are ready to whip up our actual form. We’ll want to maintain some state, specifically the url type, the url value, and an error state (which will just be a boolean for now).

We’ll use our validator functions to know, given the urlType, whether our url is valid. We’ll check this value in our onSave function which is invoked when pressing the save button or. We only want to show that there is an error if the user clicks away from an input or if they click save and the value is invalid, so we’re having error and isValid as two separate things.

type UrlType = 'email' | 'telephone';

const Form = () => {

const [urlType, setUrlType] = useState<UrlType>('telephone');

const [url, setUrl] = useState('');

const [error, setError] = useState(false);

const clearError = () => setError(false);

// this is an IIFE: an Immediately Invoked Function Expression. It lets us get

// around the fact that javascript's switch statements do not themselves return

// a value as is the case in other languages like rust/ruby.

const isValid = (() => {

switch (urlType) {

case 'email':

return isEmailUrlValid(url);

case 'telephone':

return isTelephoneUrlValid(url);

}

})();

const validate = () => {

setError(!isValid);

};

const onSave = () => {

if (isValid) {

alert(`Saved url ${url}`);

} else {

alert(`invalid url: ${url}`);

}

};

const tab = (() => {

switch (urlType) {

case 'email':

return (

<EmailTab

url={url}

setUrl={setUrl}

onSave={onSave}

onBlur={validate}

error={error}

clearError={clearError}

/>

);

case 'telephone':

return (

<TelephoneTab

url={url}

setUrl={setUrl}

onSave={onSave}

onBlur={validate}

error={error}

clearError={clearError}

/>

);

}

})();

return (

<div className="form">

<label>Link Type</label>

<select

value={urlType}

onChange={event => {

setUrlType(event.target.value as UrlType);

setUrl('');

}}

>

<option value="email" label="email" />

<option value="telephone" label="telephone" />

</select>

{tab}

<p>here's the current value: {url}</p>

<button onClick={onSave}>Save</button>

</div>

);

};

Not too shabby! Right as we begin to turn our attention to our tab components, a blinding yellow light appears before us, and from it emerges the Oracle Of Type Safety. She tells us that she noticed in the onChange event for our urlType select we assert that event.target.value has type UrlType.

We protest, ‘Yes, but if we hadn’t done that, typescript would get mad because it thinks event.target.value could be any string value, but setUrlType only accepts a value of type UrlType! We know that the only two options in the select are ‘email’ and ‘telephone’, so we had no choice but to tell typescript we know that the value will always be a UrlType!’

‘YOU ALWAYS HAVE A CHOICE’ The Oracle snaps. ‘You could have done the following:’

onChange={event => {

if (event.target.value === 'email' || event.target.value === 'telephone') {

setUrlType(event.target.value);

setUrl('');

} else {

console.error(`unexpected urlType value: ${event.target.value}`)

}

}}

This looks a little… excessive.

She continues, 'Every time you use a type assertion you are telling Typescript that you know better than it does about what possible values there can be. But this can lead to arrogance and unexpected issues at runtime. Typescript wants to help you, but you make it ever so slightly blinder with every type assertion, and if you over-do it, you'll end up with all the annoyances of typing but with none of the benefits'

As we ponder this option, a blinding blue light appears and now before us stands the Knight of Expressive Code, who says: 'BE SILENT BOTH OF YOU'. The Oracle crosses her arms and looks away, and we suspect that the two have a rocky history. The Knight continues: 'Although type assertions often hinder Typescript's ability to help you, in this case we need to consider the reader, who will be confused by the fact that we're seriously considering the possibility that other values might appear, when in reality it's just not going to happen. In an ideal world we could pass a type to the select component itself to restrict the permitted values of each option, which would then allow our onChange callback to be similarly typed, but… I don't actually know if that's possible. May as well just use the type assertion here'.

At this point the Knight and the Oracle get into a very heated debate and we slowly tiptoe out of the room, resolving to leave the type assertion there but also to heed the Oracle's warning from here on.

Returning our attention to the problem at hand after that unexpected digression, we can now add our tabs:

interface TabProps {

url: string;

setUrl: (s: string) => void;

onBlur: () => void;

error: boolean;

clearError: () => void;

}

const TelephoneTab = ({ url, setUrl, onBlur, error, clearError }: TabProps) => {

const intialValue = telephoneFromUrl(url);

const [value, setValue] = useState(intialValue);

return (

<div>

<label>Telephone</label>

<input

value={value}

className={error ? 'error' : undefined}

onChange={event => {

const updatedTelephone = event.target.value;

setValue(updatedTelephone);

setUrl(urlFromTelephone(updatedTelephone));

clearError();

}}

onBlur={onBlur}

placeholder="04 1234 5678"

/>

</div>

);

};

const EmailTab = ({ url, setUrl, onBlur, error, clearError }: TabProps) => {

const initialValue = emailFromUrl(url);

const [value, setValue] = useState(initialValue);

const onChange = (dataType: 'email' | 'subject' | 'body') => (

event: React.ChangeEvent<HTMLInputElement & HTMLTextAreaElement>

) => {

const updatedValue = { ...value, [dataType]: event.target.value };

setValue(updatedValue);

setUrl(urlFromEmail(updatedValue));

clearError();

};

return (

<div>

<label>Email address</label>

<input

value={value.email}

onChange={onChange('email')}

onBlur={onBlur}

className={error ? 'error' : undefined}

/>

<label>Subject</label>

<input value={value.subject} onChange={onChange('subject')} />

<label>Body</label>

<textarea value={value.body} onChange={onChange('body')} />

</div>

);

};

Okay, not bad. Something that is a little concerning is that our Form component is going to get quite bloated as we add more tabs: currently we have a switch statement inside our isValid IIFE, as well as our tab IIFE, and we need to add a new option to the urlType select for each new tab as well. If only there was some way to fix this up…

Chapter 2: Wizardry (code sandbox)

As we ponder how to clean up these switch statements, a blinding purple light appears and from it emerges the Wizard of Abstraction. He leans close and whispers in our ear: ‘Would you like to learn a spell?’

Of course we would!

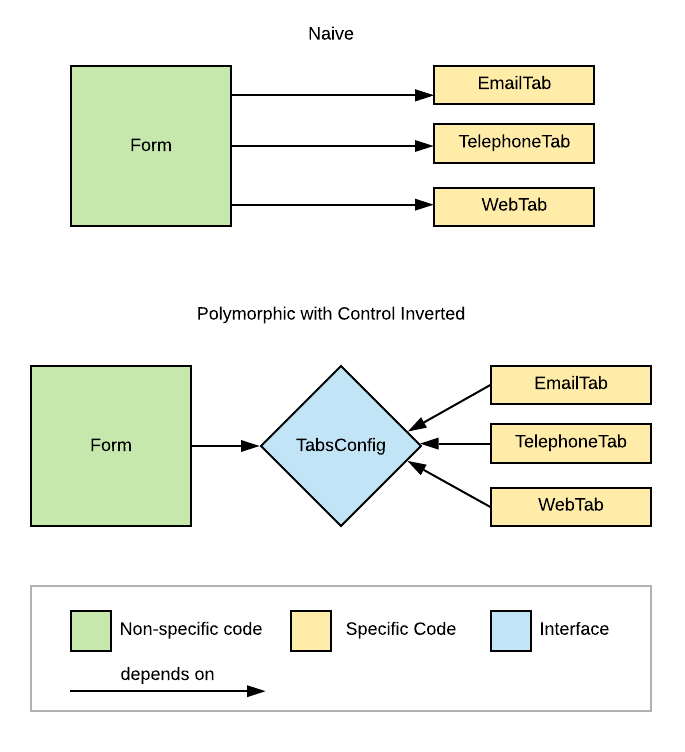

‘It’s simple,’ he begins while stroking the orb atop his staff, ‘you have some general code, in this case your Form component, which has knowledge about specific code, in this case the tabs that it renders, and their validation logic. Because the form depends on them, it needs to change every time a new tab is added, by adding that new tab to a switch statement. But if we come up with an interface that expresses the common behaviour of our various tabs, we can slice that annoying dependency in half’ (the Wizard theatrically slices the air with his staff), ‘such that the Form knows about the interface and the tabs know about the interface, but the Form and the tabs know nothing about eachother.’

‘The spell is named “POLYMORPHISM”. Poly means many, and morph means variant, which is to say that we will introduce an interface to handle many variants of the same thing’.

You cast the spell and the new code appears:

interface Tab {

isValid: (url: string) => boolean;

component: React.FC<TabProps>;

}

const tabsConfig = {

email: {

isValid: isEmailUrlValid,

component: EmailTab,

},

telephone: {

isValid: isTelephoneUrlValid,

component: TelephoneTab,

},

};

type UrlType = keyof typeof tabsConfig; // 'email' | 'telephone'

const Form = () => {

const [urlType, setUrlType] = useState<UrlType>('email');

const [url, setUrl] = useState('');

const [error, setError] = useState(false);

const clearError = () => setError(false);

const tab = tabsConfig[urlType];

const TabComponent = tab.component;

const isValid = tab.isValid(url);

const validate = () => {

setError(!isValid);

};

const onSave = () => {

validate();

if (isValid) {

alert(`Saved url ${url}`);

} else {

alert(`invalid url: ${url}`);

}

};

return (

<div>

<select

value={urlType}

onChange={event => {

setUrlType(event.target.value as UrlType);

setUrl('');

}}

>

{/* No more hardcoded options! */}

{Object.keys(tabsConfig).map(key => (

<option key={key} value={key} label={key} />

))}

</select>

{/* Depending on which tab is selected, this TabComponent will really be

an EmailTab or a TelephoneTab

*/}

<TabComponent

url={url}

setUrl={setUrl}

onBlur={validate}

error={error}

clearError={clearError}

/>

<p>here's the current value: {url}</p>

<button onClick={onSave}>Save</button>

</div>

);

};

The Wizard sees the result, chortles to himself and vanishes. Not bad! We’ve now got a Tab interface which the Form (general code) knows about, and which the values of our tabsConfig object (specific code) must conform to, but the Form no longer knows about the tabs themselves, and so instead of using switch statements all over the place, it just goes:

const tab = tabsConfig[urlType];

const TabComponent = tab.component;

const isValid = tab.isValid(url);

We are now also deriving UrlType from our config object, and using the keys of that object to generate the options in our urlType select box.

We are feeling pretty good about this code now, however before we get the chance to go and support more tab types, we hear a strong wind in the distance… hang on, that’s not natural wind, that’s the sound of wings flapping. The ground shakes and we turn around to find ourselves looking up the snout of the evil Dragon Of New Requirements, whose sinister grin tells us that we might have some new requirements on our hands.

‘You know’, the Dragon begins, giving itself a manicure with a (probably) stolen dagger, ‘I was just talking to the man who sent you on this quest in the first place’. The Dragon is momentarily distracted by a passing goat which soon finds itself flung into the air and down the Dragon’s throat, followed by a fiery burp. The Dragon continues, ‘And I couldn’t help but notice that your current solution actually misses one of the quest-giver’s requirements’.

The Dragon savours the silence as we await in terror for what’s to come.

‘The quest-giver wants the state of each tab to be persisted, so that if you start working on an email URL, then switch to telephone and switch back again, the email URL you had been building is still there. Any questions?’

‘Yes, why are we only learning about this now?’ we respond, indignant.

‘Because you were too lazy to ask the quest-giver whether that’s what they wanted when you had the chance. You know, they really should call me the Dragon Of Old Requirements’

‘How about the Dragon Of Not-Required?’ we mutter under our breath.

‘What was that?’ the dragon snaps.

‘Nothing. Thanks for the heads up’.

The dragon lets out a deafening laugh that blasts flames into the sky and then leaps into the air, flying across the lands in search of another person’s day to ruin. A timid man asks us if we’ve seen his goat, but we have no time for idle chit-chat. We have a requirement to satisfy…

Chapter 3: Persistence (code sandbox)

If we want to persist each tab’s state, we’ll need to store it in our parent Form component. Luckily for us, there’s not much to it: we just need to know what value type is being used in each tab component, and then we can manage that value type from the Form. We could just store the url itself and then load that back into the inputs when we switch back to a tab, but we can imagine new kinds of tabs where you might lose information with that approach.

Let’s chuck this in our Form component (and remove the corresponding useStates from the tab components):

const Form = () => {

// ...

const [telephone, setTelephone] = useState(telephoneFromUrl(''));

const [email, setEmail] = useState(emailFromUrl(''));

const tabState = (() => {

switch (urlType) {

case 'email':

return { value: email, setValue: setEmail };

case 'telephone':

return { value: telephone, setValue: setTelephone };

}

})();

// ...

};

Then, when we render our TabComponent, we just need to pass in the tabState:

<TabComponent

url={url}

setUrl={setUrl}

onBlur={validate}

error={error}

clearError={clearError}

tabState={tabState}

/>

Now we’ll need to accept tabState in our props… although this is a little tricky. Our value could be an Email or a string. Let’s start by properly adding a type for Email (so far it’s been implicit):

type Email = {

email: string;

subject: string;

body: string;

};

And now we need to allow our TabProps interface to deal with either value types of Email or string.

type ValueType = string | Email;

interface TabProps {

url: string;

setUrl: (s: string) => void;

onBlur: () => void;

error: boolean;

clearError: () => void;

tabState: {

value: ValueType;

setValue: React.Dispatch<React.SetStateAction<ValueType>>;

};

}

Nice! Alright now… hang on, blinding yellow light appearing again, who had that colour?… ah the Oracle Of Type Safety. She is looking pissed off.

‘YOU ARE A FOOL’ she begins, probably spiteful that we ignored her advice last time around.

‘Guilty as charged’ we respond.

‘What you are saying with that interface is that the value can be either a string or an Email, and the setValue function can take either a string or an Email. But that means that you’re allowing for value to be a string, but for a setValue to take an Email, which makes absolutely no sense. Also, you’re adding an unnecessary dependence on the specific value types that your tabs handle. For each new value type, you’ll need to append it to the ValueType type.’

‘So what should we do?’ we ask.

The Oracle pauses for a moment, and responds: ‘I’m afraid you have no choice: you need to make the interface generic over the value type. You can do this by removing the ValueType type and instead having a type parameter in your TabProps interface of the same name like so:’

interface TabProps<ValueType> {

url: string;

setUrl: (s: string) => void;

onBlur: () => void;

error: boolean;

clearError: () => void;

tabState: {

value: ValueType;

setValue: React.Dispatch<React.SetStateAction<ValueType>>;

};

}

‘Then’, she continues, ‘when you actually use the TabProps interface in your code, you can pass the concrete type in like so:

const EmailTab = ({

url,

setUrl,

onBlur,

error,

clearError,

tabState: { value, setValue },

}: TabProps<Email>) => {

// ...

};

This sounds pretty cool, but it’s also a lot to take in at once. ‘What does the Knight of Expressive Code have to say about this?’ we ask, and before we can finish our sentence the Knight steps out from a blinding blue light and inspects the code. Stroking his chin, he says ‘IN THIS CASE, THE ORACLE IS CORRECT, YOU ARE INDEED A FOOL’. Fond memories surface of simpler times when the Knight still had our back. The Knight continues, ‘Generic types increase the expressiveness of your code. Here you are saying, “I have this ValueType which will have a value at runtime, but for now I have no idea what it is. All that matters is that if it’s string, then value will be a string, and setValue will take a string, and if it’s Email, then value will be an Email and setValue will take an Email, et cetera”. As an example, if we ever pass value to setValue, we know for certain that nothing will break because they’re both dealing with the same type. This is all valuable information for the reader of the code, let alone the typescript compiler.’

Lesson learnt, generics can increase expressiveness and help the compiler. The Oracle admits ‘Knight of Expressive Code, you’re not so bad’ and then the two vanish.

Okay back to work. We update our TelephoneTab with the new props:

const TelephoneTab = ({

url,

setUrl,

onBlur,

error,

clearError,

tabState: { value, setValue },

}: TabProps<string>) => {

// ...

};

And then revisit our Form component. Looking at how we’ve currently got this state management setup, we suspect that the Wizard of Abstraction wouldn’t be impressed. Thanks to our switch statement, we’re back to having our Form depend on the specifics of our tabs:

const [telephone, setTelephone] = useState(telephoneFromUrl(''));

const [email, setEmail] = useState(emailFromUrl(''));

const tabState = (() => {

switch (urlType) {

case 'email':

return { value: email, setValue: setEmail };

case 'telephone':

return { value: telephone, setValue: setTelephone };

}

})();

How do we cast our POLYMORPHISM spell here?

Chapter 4: The Rabbit Hole (code sandbox)

Here’s the plan: we’re going to create a hook called useTab which will take our tabsConfig and invoke a useState hook for each tab, but then only return the state we need for the current tab. We’ll start by making our config type explicit so we can use it in our hook:

type TabsConfig = typeof tabsConfig;

Next we’ll make our hook. We’re going to use lodash’s mapValues function to take our config and return an object with the same keys but where the values are all tab states.

const useTab = (config: TabsConfig, urlType: UrlType) => {

const tabStates = mapValues(config, tabConfig => {

const [value, setValue] = useState(tabConfig.valueFromUrl(''));

return { value, setValue };

});

return tabStates[urlType];

};

Doing this yields an ES-lint error:

React Hook “useState” cannot be called inside a callback. React Hooks must be called in a React function component or a custom React Hook function. (react-hooks/rules-of-hooks)

Ah yes, the rules of hooks. Well, rules were made to be broken: we’re not supposed to ever call a different number of useState hooks from one render to the next, but we know that TabsConfig will always have the same number of values because it’s a constant, meaning this lint rule doesn’t apply to us. We’ll disable that lint rule and move on;

// eslint-disable-next-line react-hooks/rules-of-hooks

const [value, setValue] = useState(tabConfig.valueFromUrl(''));

Now we have a new problem: if we hover over tabStates we’ll see that its type isn’t quite what we want:

const tabStates: {

email: {

value: string | Email;

setValue: React.Dispatch<React.SetStateAction<string | Email>>;

};

telephone: {

value: string | Email;

setValue: React.Dispatch<React.SetStateAction<string | Email>>;

};

};

our mapValues function has failed to remember which keys map to which ValueTypes! Trying to do this without lodash is no better:

const tabStates = (Object.keys(config) as UrlType[]).reduce(

(acc, curr: UrlType) => {

const tabConfig = config[curr];

// eslint-disable-next-line react-hooks/rules-of-hooks

const [value, setValue] = useState(tabConfig.valueFromUrl(''));

const tabState = { value, setValue };

return { ...acc, [curr]: tabState };

},

{}

);

Here typescript tells us that the type of tabStates is {}. Fair enough, let’s risk angering the Oracle again and put a type assertion at the end of our original approach saying that tabStates really does just contain TabStates. First we’ll need to pull that type out of our TabProps interface:

type TabState<ValueType> = {

value: ValueType;

setValue: React.Dispatch<React.SetStateAction<ValueType>>;

};

interface TabProps<ValueType> {

url: string;

setUrl: (s: string) => void;

onBlur: () => void;

error: boolean;

clearError: () => void;

tabState: TabState<ValueType>;

}

Then we need to find a way of saying that our type is similar to TabsConfig except that all the values are TabStates with corresponding ValueTypes. i.e. this:

type TabStates = {

email: TabState<Email>;

telephone: TabState<string>;

};

But of course we don’t want to have to append to this new type every time we add a new ValueType, so we need to find a way to derive it from our TabsConfig type. But how?

A blinding yellow light appears and the Oracle emerges to say ‘YOU CAN USE MAPPED TYPES AND LOOKUPS FOR THIS. Which is to say, you can get the ValueType from the return type of each tab config’s valueFromUrl function:’

type TabStates = {

[Properties in keyof TabsConfig]: TabState<

ReturnType<TabsConfig[Properties]['valueFromUrl']>

>;

};

The Oracle breaks it down for us: ‘We’re saying that our new TabStates type has the exact same keys as we have in the TabsConfig type, and that for each value, we’ve got a TabState whose type parameter (i.e. ValueType) is equal to the return type of the valueFromUrl function for the corresponding tab config. Pretty basic stuff really’.

Before we can ask for clarification, the Oracle is gone.

Now we can chuck this in our hook:

const useTab = (config: TabsConfig, urlType: UrlType) => {

const tabStates = mapValues(config, tabConfig => {

// eslint-disable-next-line react-hooks/rules-of-hooks

const [value, setValue] = useState(tabConfig.valueFromUrl(''));

return { value, setValue };

}) as TabStates;

return tabStates[urlType];

};

and so now when we check what type tabStates has back inside our form we get:

const tabState: TabState<Email> | TabState<string>;

Perfect! Except that we have another problem, a problem that we actually missed even in the last chapter, which is that Typescript doesn’t like us passing in our tabState to our TabComponent:

Type 'TabState<Email> | TabState<string>' is not assignable to type 'TabState<string> & TabState<Email>'.

Type 'TabState<Email>' is not assignable to type 'TabState<string> & TabState<Email>'.

Type 'TabState<Email>' is not assignable to type 'TabState<string>'.

Types of property 'value' are incompatible.

Type 'Email' is not assignable to type 'string'.ts(2322)

Typescript is telling us: ‘the tabState variable might deal with Emails, or might deal with strings (hence the union ‘ |

’ symbol in the error), and we don’t know which it is, so our component needs to be able to handle both (hence the intersection ‘&’ symbol in the error). |

As you stroke your chin, a hissing noise in the distance grows nearer. The evil Serpent Of Typescript’s Lacking Type Inference! The serpent licks its lips with a forked tongue.

‘Confused?’ it asks mockingly. ‘Genericsss have that effect on people. Let me explain. values and functions being passed around are like keys and chests. Green keys open green chests, red keys open red chests, but if you try to unlock a chest with a mismatching coloured key, it will explode. There are three situations you can be in:

- you can see colour perfectly

- you are colour blind

- you are completely blind

You can see colour perfectly when you’re passing a concrete type to a generic function. For example when we say that our EmailTab uses TabProps<Email> we know without a doubt we’re dealing with the Email ValueType. On the other hand. when you’re inside a generic function you’re colour blind: you lose information about your types, but you can look at a key and a chest and know that given they’re the same shade, you can safely unlock the chest with the key. The third and final situation is when you are completely blind, as is the case here. You can feel around and know that you have a key and a chest, but you have no idea whether they are the same colour or not. As such, you would only want to open a chest with a key that could open chests of any colour, but we know that in the world of colour-specific keys and chests, that’s nonsensical.’

‘So what do I do?’ we ask.

‘Well’, the Serpent begins, ‘you need to find a way of telling Typescript that your TabComponent and your tabState are both the same colour.’

‘And how do we do that?’ we ask.

The Serpent gives out a long hissy laugh. ‘Well, Typescript may come out with a solution to this problem any day now and you won’t need to do anything! But it looks like you’re in a hurry so I’ll give you a hint on how to get around the current lack of type inference. I left out part of the story before about the keys and chests. The chest will explode as soon as you begin turning the key if there’s a colour mismatch, but if you’re blind and somebody passes you a chest with a key in it that’s already half-turned then you know you can safely continue turning it. Another approach would be, rather than have two different generic functions return you a key and a chest, you can always just pass them both into the function and get back whatever’s inside, so that you don’t need to worry about genericssss anymore.’

The Serpent slithers away before you get the chance to respond. Partially turned key? What does that have to do with anything? Then you receive a flashback to when somebody mentioned partial function application to you. Aha! Components are just functions, so maybe we can get our hook to return the TabComponent itself, with the tabState prop already given to it. Something like this (we’ll ignore the isValid variable for now):

const useTab = (tabsConfig: TabsConfig, urlType: UrlType) => {

const tabStates = mapValues(tabsConfig, tab => {

const TabComponentAux = tab.component;

// eslint-disable-next-line react-hooks/rules-of-hooks

const [value, setValue] = useState(tab.valueFromUrl(''));

const tabState = { value, setValue };

const TabComponent = (props: Omit<TabProps<unknown>, 'tabState'>) => (

<TabComponentAux tabState={tabState} {...props} />

);

return { TabComponent };

});

return tabStates[urlType];

};

// ...

const Form = () => {

// ...

const { TabComponent } = useTab(tabsConfig, urlType);

// ...

<TabComponent

url={url}

setUrl={setUrl}

onBlur={validate}

error={error}

clearError={clearError} // no longer passing tabState in here

/>;

// ...

};

This is a truly ugly looking hook at this point, and typescript is already lining up some red squigglies to complain about what we’re doing, but before we even get the chance to consider those, we notice that this approach actually doesn’t work at runtime: every time we type a key, our input loses focus? Why is that?

An orange blinding light appears and from it struts the Raja of React Reconciliation, and he says ‘HAVE YOU NOT READ THE DOCS? From one render to the next, if an element of one component type is replaced with an element of another component type in the virtual DOM, the entire subtree is destroyed and rebuilt, regardless of whether the two elements contained the exact same contents! Every time you define the TabComponent variable inside the useTab hook, you are creating a brand new function and that means a brand new component! So you lose focus on each keypress because each keypress triggers a re-render of the Form component which in turn calls useTab again which replaces the TabComponent in the virtual DOM and when the old input element dies it takes the focus with it’

‘Surely we can fix that with something like useMemo so that we’re not redefining the function each time?’ we ask.

The Raja laughs and says ‘FOOL! The whole point of useMemo is for when you expect the value not to change, but whenever the user types a character, tabState will change, and so TabComponent will need to be redefined so that it’s closing over the new tabState!’

‘What about useRef’? we ask.

The Raja thinks about this for a while, stroking his chin, and then asks ‘do you really want to introduce a useRef here? Doesn’t that tell you that you’re doing something fundamentally wrong?’

‘I JUST WANT TO PERSIST STATE ACROSS MY TABS!’ we scream but the Raja has already vanished.

Chapter 5: The Last Stand (code sandbox)

Now what? The Serpent did mention an alternative approach: rather than returning a partially applied component from our hook, we can return the element itself. In effect we’re receiving the key (tabState) and the chest (TabComponent) in the hook and then returning what’s inside (the element). That way we won’t have any issues with react’s reconciliation logic because we’ll always be using the same component for a given tab.

This won’t be as simple as partially applying tabStates to the component however, because we need to pass the TabComponent all of its required props from within the hook, not just the tabState as we were passing before. That means we’ll need to pass more arguments to our hook.

Let’s give this a try:

const useTab = (

tabsConfig: TabsConfig,

urlType: UrlType,

url: string,

setUrl: React.Dispatch<React.SetStateAction<string>>,

error: boolean,

setError: React.Dispatch<React.SetStateAction<boolean>>

) => {

const tabStates = mapValues(tabsConfig, tab => {

const TabComponent = tab.component;

// eslint-disable-next-line react-hooks/rules-of-hooks

const [value, setValue] = useState(tab.valueFromUrl(''));

const tabState = { value, setValue };

const isValid = tab.isValid(value);

const validate = () => {

setError(!isValid);

};

const clearError = () => setError(false);

const tabElement = (

<TabComponent

url={url}

setUrl={setUrl}

onBlur={validate}

error={error}

clearError={clearError}

tabState={tabState}

/>

);

return { tabElement, isValid, validate };

});

return tabStates[urlType];

};

// ...

const Form = () => {

const [urlType, setUrlType] = useState<UrlType>('email');

const [url, setUrl] = useState('');

const [error, setError] = useState(false);

const { tabElement, isValid, validate } = useTab(

tabsConfig,

urlType,

url,

setUrl,

error,

setError

);

const onSave = () => {

validate();

if (isValid) {

alert(`Saved url ${url}`);

} else {

alert(`invalid url: ${url}`);

}

};

// ...

return (

// ...

{ tabElement }

// ...

);

};

Well, at least it’s not losing focus on each typed character anymore. But it’s not great to look at, and we still have type errors. When we pass value into tab.isValid we get:

Argument of type 'string | Email' is not assignable to parameter of type 'string'.

Type 'Email' is not assignable to type 'string'.

Likewise we’re getting the same error as earlier when passing in tabState to our TabComponent:

Type '{ value: string | Email; setValue: React.Dispatch<React.SetStateAction<string | Email>>; }' is not assignable to type 'TabState<string> & TabState<Email>'.

Type '{ value: string | Email; setValue: React.Dispatch<React.SetStateAction<string | Email>>; }' is not assignable to type 'TabState<string>'.

Types of property 'value' are incompatible.

Type 'string | Email' is not assignable to type 'string'.

Type 'Email' is not assignable to type 'string'.ts(2322

How do we dig ourselves out of this hole? We can extract out a generic function so that we can be explicit about what the ValueType should be:

const useTab = (

tabsConfig: TabsConfig,

urlType: UrlType,

url: string,

setUrl: React.Dispatch<React.SetStateAction<string>>,

error: boolean,

setError: React.Dispatch<React.SetStateAction<boolean>>

) => {

const getTabState = <ValueType extends unknown>(tab: Tab<ValueType>) => {

const TabComponent = tab.component;

// eslint-disable-next-line react-hooks/rules-of-hooks

const [value, setValue] = useState(tab.valueFromUrl(''));

const tabState = { value, setValue };

const isValid = tab.isValid(value);

const validate = () => {

setError(!isValid);

};

const clearError = () => setError(false);

const tabElement = (

<TabComponent

url={url}

setUrl={setUrl}

onBlur={validate}

error={error}

clearError={clearError}

tabState={tabState}

/>

);

return { tabElement, isValid, validate };

};

const tabStates = {

email: getTabState<Email>(tabsConfig.email),

telephone: getTabState<string>(tabsConfig.telephone),

};

return tabStates[urlType];

};

It just so happens we actually don’t need to explicitly pass our Email and string types here because type inference can work it out for us:

const tabStates = {

email: getTabState(tabsConfig.email),

telephone: getTabState(tabsConfig.telephone),

};

But this code is still problematic because we’re back to having to update our supposedly general code when we add a new tab. Is there some way to move this logic into the config object? What if we had our getTabState in the config object itself somehow? Nope, that will not work.

Chapter 6: Collapse (code sandbox)

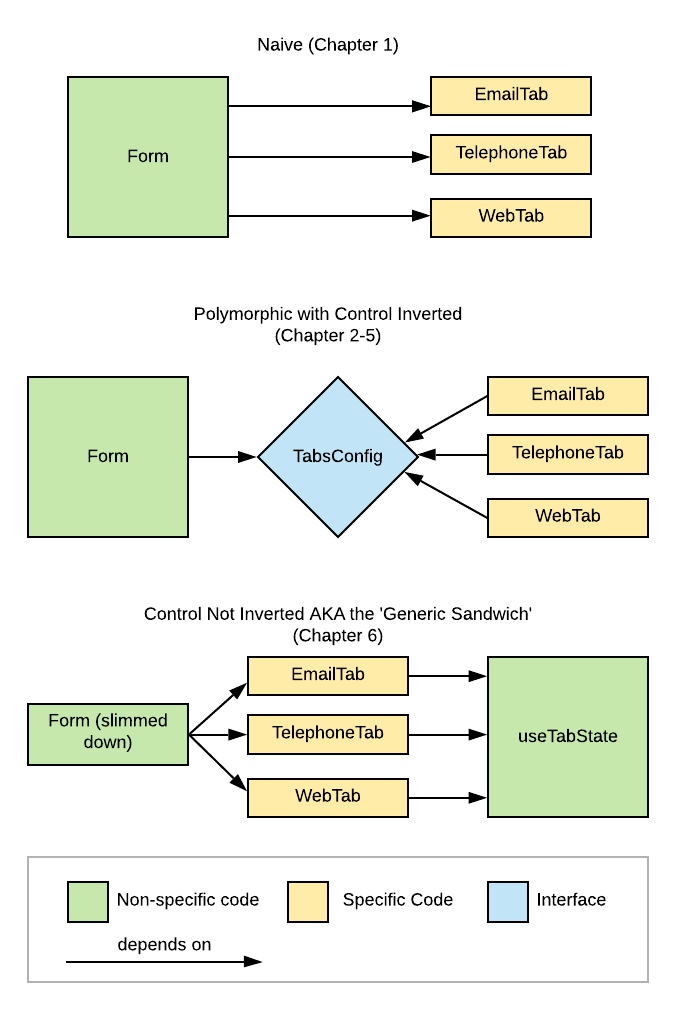

Looking at our hook, it’s not very straightforward what’s going on: we’re creating an element for each tab but then only returning one of them, and the use of the generic getTabState function does not make for easy reading. You suspect that if the Wizard of Abstraction had a solution, he would have appeared by now.

Instead, a blinding red light appears and out flies the Witch of De-Abstraction on a broomstick. Looping around, she parks her broomstick and approaches. ‘HAVING TROUBLE WITH AN ABSTRACTION?’ She begins. ‘Maybe it’s time you thought about whether it’s causing more pain than it’s worth’.

We respond, ‘It was working great until that evil Dragon gave us a requirement for persisted state. Now there’s no way to get polymorphic behaviour without sprinkling type assertions everywhere and blinding Typescript. Now we’ve got a hook which makes other hooks which return elements, one of which we actually render’.

‘A tragedy, truly.’, the witch replies with mock empathy, ‘The feeling you get when you’re so close to that perfect abstraction, but then some unforseen requirement gets in the way and nobody can understand the code anymore. And I suppose the Wizard Of Abstraction didn’t care to teach you how to reverse the POLYMORPHISM spell?’

‘I’m not so sure that we want to reverse it’ we say. ‘These components all behave basically the same: using an abstraction lets us factor out the duplicated code into one centralised place’

‘Nonsense’, the Witch cackles, ‘you don’t need polymorphism to remove duplication. Let’s see if you can learn a new spell: DISMANTLE-ABSTRACTION.

We say the words and we end up with a quite different Form component:

// no more tabsConfig object

const urlTypes = ['email', 'telephone'] as const;

type UrlType = typeof urlTypes[number]; // 'email' | 'telephone'

const Form = () => {

const [urlType, setUrlType] = useState<UrlType>('email');

const [url, setUrl] = useState('');

// isValid is now stateful, and is managed by the current tab

const [isValid, setIsValid] = useState(true);

const onSave = () => {

if (isValid) {

alert(`Saved url ${url}`);

} else {

alert(`invalid url: ${url}`);

}

};

const commonTabProps = (type: UrlType) => ({

url: url,

setUrl: setUrl,

setIsValid,

display: type === urlType,

});

return (

<div>

<select

value={urlType}

onChange={event => {

setUrlType(event.target.value as UrlType);

}}

>

{urlTypes.map(key => (

<option key={key} value={key} label={key} />

))}

</select>

{/* each tab is responsible for hiding itself if not selected */}

<EmailTab {...commonTabProps('email')} />

<TelephoneTab {...commonTabProps('telephone')} />

<p>here's the current value: {url}</p>

<button onClick={onSave}>Save</button>

</div>

);

};

‘I’ll walk you through it’, the Witch begins. ‘Rather than controlling each tab’s value from the Form component, we’re now only controlling the isValid state, whose value is set by the current tab. We now render all tabs at once, but pass a display prop down so that only the current tab will actual return something to display. As for the tabs themselves, here’s what they look like:

interface TabProps {

url: string;

setUrl: (s: string) => void;

setIsValid: (isValid: boolean) => void;

display: boolean;

}

const TelephoneTab = ({ url, setUrl, setIsValid, display }: TabProps) => {

const intialValue = telephoneFromUrl(url);

const [value, setValue] = useState(intialValue);

const [error, setError] = useState(false);

useEffect(() => {

if (display) {

setIsValid(isTelephoneUrlValid(value));

setUrl(urlFromTelephone(value));

}

}, [display, setIsValid, value, setUrl]);

if (!display) {

return null;

}

const onBlur = () => {

const isValid = isTelephoneUrlValid(value);

setError(!isValid);

};

return (

<div>

<label>Telephone</label>

<input

value={value}

className={error ? 'error' : undefined}

onChange={event => {

const updatedTelephone = event.target.value;

setValue(updatedTelephone);

setError(false);

}}

onBlur={onBlur}

placeholder="04 1234 5678"

/>

</div>

);

};

const EmailTab = ({ url, setUrl, setIsValid, display }: TabProps) => {

const [value, setValue] = useState(emailFromUrl(''));

const [error, setError] = useState(false);

useEffect(() => {

if (display) {

setIsValid(isEmailUrlValid(value));

setUrl(urlFromEmail(value));

}

}, [display, setIsValid, value, setUrl]);

if (!display) {

return null;

}

const onBlur = () => {

const isValid = isEmailUrlValid(value);

setError(!isValid);

};

const onChange = (dataType: 'email' | 'subject' | 'body') => (

event: React.ChangeEvent<HTMLTextAreaElement & HTMLInputElement>

) => {

const updatedValue = { ...value, [dataType]: event.target.value };

setValue(updatedValue);

setError(false);

};

return (

<div>

<label>Email address</label>

<input

value={value.email}

onChange={onChange('email')}

onBlur={onBlur}

className={error ? 'error' : undefined}

/>

<label>Subject</label>

<input value={value.subject} onChange={onChange('subject')} />

<label>Body</label>

<textarea value={value.body} onChange={onChange('body')} />

</div>

);

};

‘So now, each tab controls both its own value and its own error state. Whenever we type a character, we’ll set the url in the parent and say whether it’s valid.’

‘This doesn’t look very DRY’, we protest.

‘Right you are! We’ve taken top level code and moved it into our specific tabs, but there’s no reason we can’t extract out the commonalities again.’ The Witch flicks her wand and yells ‘EXTRACT-COMMON-CODE-INTO-HOOK’

interface UseTabStateArgs<ValueType>

extends Pick<TabProps, 'setUrl' | 'setIsValid' | 'display'> {

valueFromUrl: (url: string) => ValueType;

urlFromValue: (value: ValueType) => string;

isValueValid: (value: ValueType) => boolean;

}

const useTabState = <ValueType extends unknown>({

display,

setIsValid,

setUrl,

valueFromUrl,

urlFromValue,

isValueValid,

}: UseTabStateArgs<ValueType>) => {

const [value, setValue] = useState<ValueType>(valueFromUrl(''));

const [error, setError] = useState(false);

useEffect(() => {

if (display) {

setIsValid(isValueValid(value));

setUrl(urlFromValue(value));

}

// 'Man, this exhaustive deps linting rule really makes it hard to

// express intention' - Knight of Expressive Code

}, [display, setIsValid, value, setUrl, isValueValid, urlFromValue]);

const updateValue = (updatedValue: ValueType) => {

setValue(updatedValue);

setError(false);

};

const onBlur = () => {

const isValid = isValueValid(value);

setError(!isValid);

};

return { updateValue, onBlur, error, value };

};

‘So now we’ve got the handling of the value in one place, as well as onBlur and error handling. If we come across a tab which needs slightly different behaviour, we can split this into multiple hooks and then pick which ones that tab actually needs. Here’s what the tabs look like now:’

const TelephoneTab = ({ url, setUrl, setIsValid, display }: TabProps) => {

const { updateValue, onBlur, error, value } = useTabState({

setUrl,

setIsValid,

display,

valueFromUrl: telephoneFromUrl,

urlFromValue: urlFromTelephone,

isValueValid: isTelephoneValid,

});

if (!display) {

return null;

}

return (

<div>

<label>Telephone</label>

<input

value={value}

className={error ? 'error' : undefined}

onChange={event => {

const updatedTelephone = event.target.value;

updateValue(updatedTelephone);

}}

onBlur={onBlur}

placeholder="04 1234 5678"

/>

</div>

);

};

const EmailTab = ({ url, setUrl, setIsValid, display }: TabProps) => {

const { updateValue, onBlur, error, value } = useTabState({

setUrl,

setIsValid,

display,

valueFromUrl: emailFromUrl,

urlFromValue: urlFromEmail,

isValueValid: isEmailUrlValid,

});

if (!display) {

return null;

}

const onChange = (dataType: 'email' | 'subject' | 'body') => (

event: React.ChangeEvent<HTMLTextAreaElement & HTMLInputElement>

) => {

const updatedValue = { ...value, [dataType]: event.target.value };

updateValue(updatedValue);

};

return (

<div>

<label>Email address</label>

<input

value={value.email}

onChange={onChange('email')}

onBlur={onBlur}

className={error ? 'error' : undefined}

/>

<label>Subject</label>

<input value={value.subject} onChange={onChange('subject')} />

<label>Body</label>

<textarea value={value.body} onChange={onChange('body')} />

</div>

);

};

‘Pretty DRY, wouldn’t you say?’. At this point a blinding purple light appears and out pops the Wizard of Abstraction.

‘SO WE MEET AGAIN, MY ARCH-NEMESIS’ the Wizard begins. ‘Here to whisper anti-patterns into the ears of my pupil?’

‘I’m disappointed you see it that way Wizard,’ the Witch responds, ‘I thought you’d be impressed that I just cast EXTRACT-COMMON-CODE-INTO-HOOK which was a spell you came up with in the first place’.

‘You have always been disappointingly unoriginal’ the Wizard quips. ‘Let’s look at what we have here… we’re no longer using polymorphism so our Form component knows about all the tab components meaning we’ll need to modify the Form whenever we add a new tab, and there’s no way to enforce from the top level how state is managed. You’re therefore banking on the hope that each tab component makes use of the useTabState hook and honours the display prop despite having no way to enforce that behaviour in a centralised place. What’s more, the isValid variable has now become stateful because it’s needed from the Form component but can only be determined from the tab components. This means that you’ve introduced the risk of bugs caused by impossible states, where a tab forgets to set isValid and we end up with our isValid value being out-of-sync with our url value. I rate this an F’

The Witch cackles. ‘Last time I checked that cute polymorphism experiment wasn’t going so well. Hooks which call hooks which return elements? Nobody’s going to volunteer to maintain that mess. The current Form component knows about the tab children, yes, but why shouldn’t it? It’s not like it’s going to be re-used for other purposes where some new config object gets passed in: it has a very narrow range of applicability. As for each child component being rendered explicitly, that allows us to pass in any props that we know only apply to one component. Say that we add a tab which displays a select box of pre-built URLs that have been fetched from an API: with the polymorphic approach, we would need to pass the select options prop from the Form component to the generic TabComponent, despite it only actually applying to one of the tabs. Likewise with any other random props that different tabs might need.’

The Wizard goes to speak but is cut off again by the Witch: ‘With the polymorphic approach, we were trying to call specific code from a general place through an interface, which causes all kinds of headaches as the Serpent Of Typescript’s Lacking Type Inference no doubt explained. With this new approach, we’re scrapping the interface, splitting the general code into a slim top-level Form component and a useTabState hook, which the specific (tab) code can call without any Typescript difficulties because the specific code knows what ValueType to pass to the hook. I hereby call this approach the Generic Sandwich’

The Wizard now interjects: ‘Give me a break. We all know that the Serpent of Typescript’s Lacking Type Inference was twice as large this time last year, and he continues to shrink even as we speak. Why should our type system influence whether we cast polymorphism spells or invert control from specific components to generic components?’

At this point a blinding yellow light heralds the entrance of the Oracle Of Type Safety who responds ‘BECAUSE TYPE SAFETY PROTECTS YOU FROM RUNTIME ERRORS. If you can find a way to write code where Typescript can alert you to problems that would otherwise only surface at runtime, you should. If that means sacrificing some of the power that abstractions grant you, so be it’.

The room is now getting a little cramped, and it becomes even more cramped when a blinding blue light appears and out walks the Knight Of Expressive Code who says ‘TO BE HONEST, THE WITCH’S APPROACH IS EASIER TO READ. Admittedly, the fact that we’re supposedly rendering a bunch of tabs but then only one of them actually renders itself is not very expressive. But everything else is fairly easy to follow, and it would not be that hard to add another tab. The contract that the polymorphic approach enforced is not entirely lost: it’s still mostly intact through the useTab hook, and the typical developer is going to copy and paste a tab component to make another one, meaning it’s going to take quite a lot of effort to not satisfy the contract. As for the awkwardness of isValid now being stateful, we can get around that by just having a config object of validators which take the URL instead of the input values given we don’t currently have a use case for looking at the input values specifically.’

The Raja of React Reconciliation entered the room at some point just for the sake of watching the debate play out, but doesn’t have much to contribute himself.

‘ENOUGH’ We scream. ‘THIS IS ALL REALLY CONFUSING’. We take a moment to gather our thoughts. ‘Maybe there’s some approach that we haven’t considered yet.’ Just as we say this, a blinding white light appears and through it walks somebody who just read this story and thought of something that all the other characters missed. And that person says:

Shameless plug (which appears on every blog post, not just this one, so don't think that I'm opportunistically posting this specific post just for the sake of doing this plug): I recently quit my job to co-found Subble, a web app that helps you manage your company's SaaS software licences. Your company is almost certainly wasting time and money on shadow IT and unused/overprovisioned licences and Subble can fix that. Check it out at subble.com