LSD and the Wrong Abstraction

The world of software development has no shortage of smart cookies weighing in on what you should do. How to write tests, how to approach solving problems, how to structure things. So whenever I build intuition for a useful concept in my programmer life, I wonder whether that concept still has legs when imported into my human life. The idea of focusing efforts towards an MVP, a Minimum Viable Product as opposed to whatever grand plans you have for a project in the long term, is a concept I’ve found to be just as useful in diet and exercise as I have in developing a software product. Yes, in the long run you want to look like Brad Pitt in Troy, but given your history of abandoning projects out of fear let’s start by patting yourself on the back whenever you muster the courage to rock up to the gym in the first place.

There is no concept I’ve thought more about in my life as a programmer than abstraction. Not in the sense that a robyn is a bird is an animal, but more in the sense of asking if two things are essentially the same, for the sake of deciding whether to have both conform to the same interface, or to combine them into a single method/class with an extra arg that represents their differences. I’ve evolved from being an ardent advocate of the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle to being a little more reserved, especially after experiencing the pain of working with a ‘wrong’ abstraction a few times.

Whether you decide two classes are essentially doing the same thing and should be merged together, or whether you’re the guy who then splits them apart six months later, there’s always rational arguments to justify the decision. Over-abstracters (to oversimplify this to a one-dimensional spectrum) will say they don’t want to fix a bug in one place only to find it resurfaced in a separate class that should never have been separate in the first place. Under-abstracters will say it’s far easier to combine two classes than to disentangle a class that really represents two distinct things.

But behind the rational arguments there are gut feelings. Developed over years as the developer has been burnt by the failure to treat different code as similar or the failure to treat similar code as different. You can come up with a heuristic like ‘are these two methods essentially the same?’ but philosophers have been debating about whether anything has ‘essential’ properties since Aristotle, and what you often instead end up asking is ‘are these two methods essentially similar enough’? Similar enough to justify the gamble that they will evolve in lockstep. What informs that gamble is often the question of whether you believe things are, on average, more similar than they are different.

Which brings me to LSD. If you visit Drug Free World Dot Org you’ll learn about some common side effects of LSD including ‘Dilated pupils’, ‘Dry mouth’, and ‘Severe depression or psychosis’. If you visit Erowid’s LSD experience vault you’ll get a sense for how the typical trip actually goes down. Though there are plenty are trainwrecks (there’s a whole section dedicated to them) others speak to what most people have long associated with acid and hippies: oneness. Oneness with other humans, oneness with animals, oneness with the universe. A dissolving of differences. But is that an ethos worth aspiring to?

The ‘We are all one’ maxim of acid’s acolytes has always irked me. It seems sufficiently general as to be useless in practice.

A chef who randomly combines incompatible ingredients into a dish under the mantra of ‘they’re all food’ isn’t going to be a chef for long. Nor would anybody accept ‘well it’s all written in the same language’ as an argument for combining two completely different functions. Yet I also feel that when it comes to cultral beliefs, there is utility in pushing a simplified narrative for the sake of pulling people in the right direction. ‘We are all one, including murderers and human traffickers’ though true, isn’t going to gel well with the general public, but you could make money betting that anti-social behaviour and perhaps even violent crime would decrease if every billboard in the world exclaimed that ‘We are all one’ for a month. It’s certainly more appealing than ‘We are all essentially more similar than we are different, and should therefore evolve in lockstep’ (is it any wonder that nobody hires a programmer to design a billboard?)

Let’s put aside the societal-level question here and focus on the individual level. Can an individual benefit from heeding differences more than similarities? Or in this time of political division, should people take a page out of the Shulgin Index and put all differences aside?

The ‘we are all one’ crowd, whether acid-loving or not, can be identified by a tranquil, relaxed facial expression. An expression that to me almost suggests that though we are all one, some people are more one than others.

Compare that to the expression people wear when trying to look cool. Is it any surprise that when somebody wants to look cool for a photo they contort their brow as if to say ‘something is not right here, something is different, and I’m the one who noticed’.

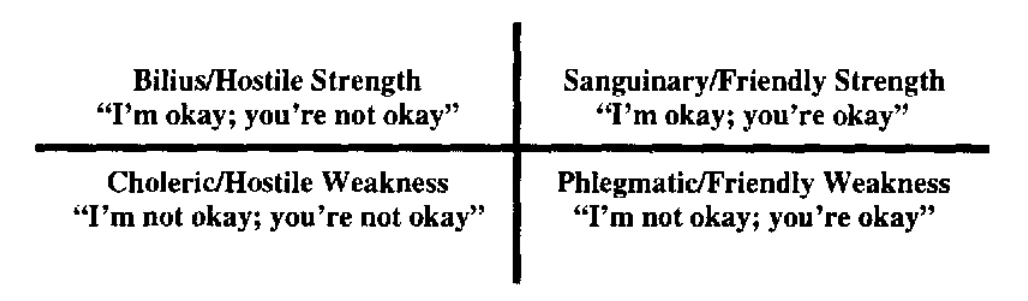

The contrast between these two presentations of people feels fundamental. Prometheus Rising, a book I’ve read just enough of to reference here, divides people into four categories based on two booleans: whether you’re okay, and whether the other person is okay.

Sanguinary is likened to a lion, and Bilius to an eagle. It’s the medieval Tetramorph. It’s Griffindoor vs Slytherin. Humanity has been slicing people up like this since antiquity. As somebody cautious of bad abstractions, one must be wary about generalisations like this, but I’ve found it insightful to realise that many of my friends fall squarely into one of these categories. The Lion is confident, friendly, and focuses on similarities. The Eagle is also confident, but is proud, and focuses on differences.

Which is better? One of my friends is a definite Eagle and for that reason wastes no time with people he perceives as incompatible. He’s charismatic and likeable, so it’s at no cost to him socially. But there has certainly been collateral damage when he’s decided somebody is unworthy. In the same way that under-abstraction can sometimes become a self-fulfilling prophecy*, in that it’s easier to have two separate classes evolve into their own distinct niches than if you had treated them as the same, so it is with human beings, and if you prematurely cast somebody as ‘other’, their resulting self-consciousness can give rise to the same undesirable traits they were unjustly ascribed with in the first place (giving the Eagle an unearned confidence in picking bad eggs).

Another friend of mine is a quintessential Lion: always including others and seeing the best in people, no matter who they are. Parties are always more fun when this person is invited; in fact they’re often the one to organise the party in the first place. Social mishaps are quickly forgiven and newcomers are treated as likeable by default: another self-fulfilling prophecy.

Comparing the two friends, it’s fairly clear which lifestyle is preferable. But in thinking through this all, it strikes me how involuntary both friend’s behaviour is. It would take a great deal of conscious effort for either of them to shift in the other direction. I think that although everybody should strive to be a good person, you should also try to know yourself. Did you enter a relationship with somebody you weren’t very compatible with and then emotionally exhaust yourself when you found out the abstraction was wrong and you had to disentangle from eachother? Do you struggle to enter into a relationship in the first place because you’re too preoccupied on incompatibilities? I think the takeaway is to learn how much these things matter to you and how much you (and the people around you!) have been burnt by under-abstracting or over-abstracting in real life.

But of course, just like in programming, it’s all on a case-by-case basis.

Addendum

* self-fulfilling prophecies in abstraction.

This may only apply to small companies but I have seen this happen a couple times and I haven’t heard it talked about online. When the product team works closely with the dev team and the dev team has sway in the direction of the product, abstractions in code can steer the course of the product. When deadlines are always tight, the dev team can say that a certain feature is not worth the investment given how it demands an unsupported use case from a tangled mess of an abstraction that’s a nightmare to work with. And then product can negotiate with them to see what is possible given the timeframe. This is the software development equivalent of Agent Smith waking up in the real world: code structure shouldn’t leak out into product decisions! But it sometimes does. All the more reason to pick your abstractions carefully.

Shameless plug (which appears on every blog post, not just this one, so don't think that I'm opportunistically posting this specific post just for the sake of doing this plug): I recently quit my job to co-found Subble, a web app that helps you manage your company's SaaS software licences. Your company is almost certainly wasting time and money on shadow IT and unused/overprovisioned licences and Subble can fix that. Check it out at subble.com