Lessons Learned Revamping Lazygit's Integration Tests

Something I don’t come across enough online is posts where the author walks through a feature they built along with all the dead-ends and refactors along the way. So this post is my attempt to add to that modest corpus with my most recent coding journey.

Today I merged a Pull request that changes the approach to integration tests in Lazygit and I figured it’s worth doing a writeup of the journey just because it touches on some interesting topics (Go, cyclic imports, interfaces vs structs, and dependencies).

The Problem

The existing approach to integration tests works like this:

- You write a bash script setting up a test repo, and then record yourself in a lazygit session situated within that repo.

- Your keystrokes and their timestamps are stored in a JSON file which is then used to replay the session when we run the test.

- You invoke a command to run the test (whether through

go testor a convenient terminal UI) and if by the end of the test run the resultant repo doesn’t match the expected repo, the test fails.

This approach is probably the fastest possible way to write a new test. You typically find an existing test directory (which contains the test definition, recording, and expected repo), duplicate it, then tweak the setup.sh script to do what you want, and then record a session.

Unfortunately, the ease of creation comes at the cost of ease of maintenance:

- A test can only fail due to a snapshot mismatch, so it’s not until the end of the test that you are told something went wrong, and it’s not always obvious when it went wrong

- Some tests require awkward actions to work around the snapshot requirements, like having to reword a revert commit in order to have a deterministic commit message (a revert will by default have the original commit hash in the message)

- A big JSON blob of recorded keypresses and timestamps tells you nothing about the intention behind the actions

- When watching a recording it’s not obvious if a particular keypress was deliberate or a slip of the recorder’s finger

- If we change the default keybinding for an action, you need to go and re-record the whole test

- Recordings are replayed at a fast speed to reduce test duration, but a failure means re-running the whole test at a slower speed, and so on, meaning it takes a while for CI to actually fail a test.

The Plan

The new testing pattern would take a different approach: you would define a test entirely in code, using abstractions for setting up the initial repo state, driving the gui, and asserting on the gui’s state. This has a few benefits, for example:

- It’s easier to create abstractions of common actions e.g. you could have a method for switching to a particular window or typing a string of characters into a prompt.

- It’s easier to express your intention throughout the test with comments

- You can assert on the state of the gui after each action to ensure the test fails as soon as something goes wrong, with an appropriate error message

- Tests fail faster because in the event of a failure caused by our robot user typing too fast, rather than retry the entire test at a slower speed, you can instead retry a single assertion

The Journey

I started by coming up with some interfaces for the components I needed. I wanted the following four things:

- IntegrationTest, for defining a test

- Shell, for allowing the test to shell out commands (e.g. to git)

- Input, for allowing the test to input things

- Assert, for allowing the test to assert things

Here’s what my IntegrationTest interface looked like:

type IntegrationTest interface {

Name() string

Description() string

// this is called before lazygit is run, for the sake of preparing the repo

SetupRepo(Shell)

// this gives you the default config and lets you set whatever values on it you like,

// so that they appear when lazygit runs

SetupConfig(config *config.AppConfig)

// this is called upon lazygit starting

Run(Shell, Input, Assert, config.KeybindingConfig)

// e.g. '-debug'

ExtraCmdArgs() string

// for tests that are flakey and when we don't have time to fix them

Skip() bool

}

And here’s what one of the tests looked like (excuse the length):

type Commit struct {}

// ensuring we implement the interface

var _ types.IntegrationTest = &Commit{}

func (self *Commit) Name() string {

// getTestNameFromFile uses runtime information to obtain the current file name

// so that you can easily find where the test lives if it fails on CI.

return getTestNameFromFile()

}

func (self *Commit) Description() string {

return "Staging a couple files and committing"

}

func (self *Commit) Skip() bool {

return false

}

func (self *Commit) ExtraCmdArgs() string {

return ""

}

func (self *Commit) SetupRepo(shell types.Shell) {

shell.CreateFile("myfile", "myfile content")

shell.CreateFile("myfile2", "myfile2 content")

}

func (self *Commit) SetupConfig(config *config.AppConfig) {

}

func (self *Commit) Run(

shell types.Shell,

input types.Input,

assert types.Assert,

keys config.KeybindingConfig,

) {

assert.CommitCount(0)

input.Select()

input.NextItem()

input.Select()

input.PushKeys(keys.Files.CommitChanges)

commitMessage := "my commit message"

input.Type(commitMessage)

input.Confirm()

assert.CommitCount(1)

assert.HeadCommitMessage(commitMessage)

}

(You may have noticed two departures from Go’s idioms in that snippet: the use of a self receiver name and an explicit interface implementation check: both of which I argue for in my Go’ing Insane series).

One Struct vs Many

A couple things bothered me about having each test as its own type though:

- Each test had the same implementation for the

Namemethod and fixing that with struct embedding just meant shifting the duplication to the use of the embedded struct. - Finally, the

SetupConfig,ExtraCmdArgsandSkipmethods would rarely be used (based on experience with the old setup) but took up space nonetheless, distracting from the important parts. Again, an embedded struct could help, but it meant more boilerplate. - The easiest way to start writing a new test is to copy+paste an existing one, but then you’d have to update all those pesky function signatures to use the new type name (classic Go)

- None of the test structs needed any fields. Storing bespoke state/dependencies on struct fields is one of the reasons you might want to have multiple structs instead of just one.

Given these concerns, I switched to having a single struct where the old methods were now passed in as arguments to its constructor:

var Commit = types.NewTest(types.NewTestArgs{

Description: "Staging a couple files and committing",

SetupRepo: func(shell types.Shell) {

shell.CreateFile("myfile", "myfile content")

shell.CreateFile("myfile2", "myfile2 content")

},

Run: func(shell types.Shell, input types.Input, assert types.Assert, keys config.KeybindingConfig) {

assert.CommitCount(0)

input.Select()

input.NextItem()

input.Select()

input.PushKeys(keys.Files.CommitChanges)

commitMessage := "my commit message"

input.Type(commitMessage)

input.Confirm()

assert.CommitCount(1)

assert.HeadCommitMessage(commitMessage)

},

})

The constructor handles missing args by using defaults, and complains at runtime if the required args are missing (If you want an idea for a Go linter, make one which allows you to define mandatory struct fields via comments: wouldn’t take long to write and you’d get lots of street cred).

Unstable Interfaces

Initially the Input and Assert interfaces were implemented in the gui package (where most of the action in lazygit happens). I quickly found that it was a pain in the ass to maintain these, as there are many things you may want to input, and many things you may want to assert. Every new method I added meant updating the implementation struct in the gui package as well as the interface back in the integration package. Interfaces work best when they are stable, and if you find yourself with an interface that has only one implementation, where you’re frequently adding new methods, you may have picked the wrong abstraction.

InputImpl, my input implementation¹, had a pressKey method which actually made use of gui-specific code, but I had all these other convenience methods that were just building on top of that method without needing access to any internals. For example:

func (self *InputImpl) SwitchToStatusWindow() {

self.pressKey(self.keys.Universal.JumpToBlock[0])

}

func (self *InputImpl) SwitchToFilesWindow() {

self.pressKey(self.keys.Universal.JumpToBlock[1])

}

func (self *InputImpl) SwitchToBranchesWindow() {

self.pressKey(self.keys.Universal.JumpToBlock[2])

}

...

So I extracted out a new abstraction: GuiDriver, which so far has proven far more stable:

type GuiDriver interface {

PressKey(string)

Keys() config.KeybindingConfig

CurrentContext() types.Context

Model() *types.Model

Fail(message string)

...

// couple other things

}

And now I’ve got my Input struct living in the integration package, taking GuiDriver as a dependency. Same deal with Assert. I’ve ditched the interfaces again because I figured I didn’t need the overhead of an unstable interface that would only be used within the one package. The GuiDriver interface is defined in the integration package and the implementation is in the gui package. Now my gui package depends only on the following interface for my tests:

type interface IntegrationTest {

SetupConfig(config *config.AppConfig)

Run(GuiAdapter)

}

And I’ve scrapped the original IntegrationTest interface because I wasn’t using it for anything (and it wasn’t necessary for unit tests). It’s also worth noting that my IntegrationTest struct implements the above interface and in the Run method it takes the gui adapter and instantiates the Input and Assert structs with it to pass onto the inner Run function: further lending credence to the idea of having a single test struct rather than many.

Import Cycles

In the original testing approach, when invoking lazygit in test mode we would pass it a LAZYGIT_RECORDING_PATH environment variable which would tell lazygit where to find the recording JSON to replay. In the new approach we instead need to pass the name of a test for lazygit to load, which it does by iterating through all the tests until it finds a match. This introduces a new problem: if lazygit depends on our tests, and our tests depend on lazygit, then we have a cyclic dependency between packages. Go disallows this (with an error message that could be a little more detailed in my opinion) and with good reason: cyclic dependencies cause all kinds of problems. One particular problem in our case is that we don’t want to be shipping a binary with a bunch of test code baked in, which is what happens when you have your code depend on your tests.

To resolve this I used some good old-fashioned dependency injection so that the entrypoint of my code³ actually receives an integration test interface as an argument (which may be nil if we’re just running lazygit normally). Unfortunately, when you want to exercise dependency injection at the level of a program², you either need to resort to conditional compilation, or just have a separate main.go which you invoke when running an integration test, which itself has the dependency on the tests. I went with the latter.

So here’s my (abridged) root-level main.go file:

import (

"github.com/jesseduffield/lazygit/pkg/gui"

)

func main() {

gui.Start(nil)

}

and here’s my (also abridged) test-injector main.go file:

import (

"fmt"

"os"

"github.com/jesseduffield/lazygit/pkg/gui"

integrationTests "github.com/jesseduffield/lazygit/pkg/integration/tests"

integrationTypes "github.com/jesseduffield/lazygit/pkg/integration/types"

)

func main() {

integrationTest := getIntegrationTest()

gui.Start(integrationTest)

}

func getIntegrationTest() integrationTypes.IntegrationTest {

integrationTestName := os.Getenv("LAZYGIT_TEST_NAME")

for _, candidateTest := range integrationTests.Tests {

if candidateTest.Name() == integrationTestName {

return candidateTest

}

}

panic("Could not find integration test with name: " + integrationTestName)

}

Notice that I’m importing both an integrationTests package and an integrationTypes package. The reason for splitting those is so that the rest of the lazygit code can depend on the IntegrationTest and GuiDriver interfaces without actually needing to depend on all the other integration test code. It’s only in this injector file that isn’t part of the final lazygit binary where we depend on the actual tests.

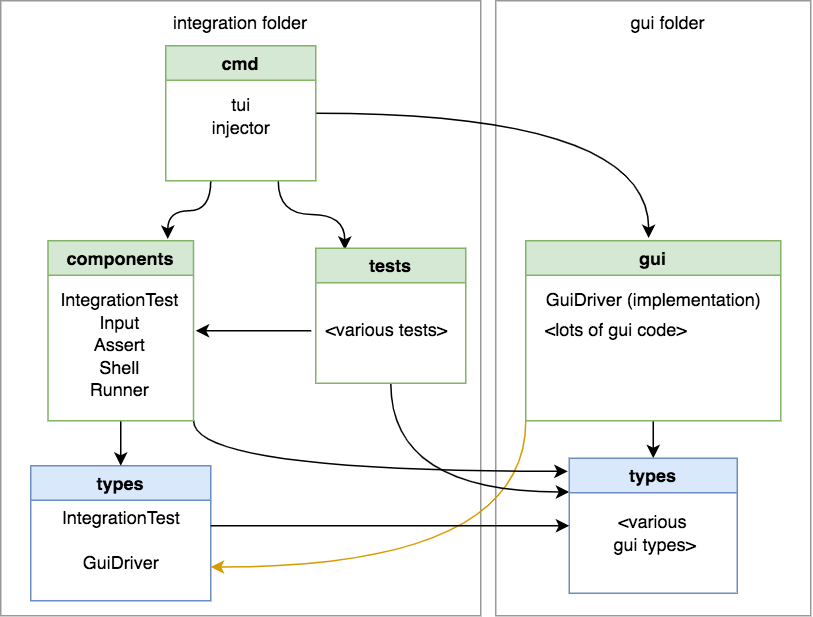

Here’s how the package is arranged now:

That yellow arrow bothers me because I feel that all arrows from one folder to the next should go in the same direction (even though Go is satisfied because there’s no cycles among the packages themselves). There are a few things I could do:

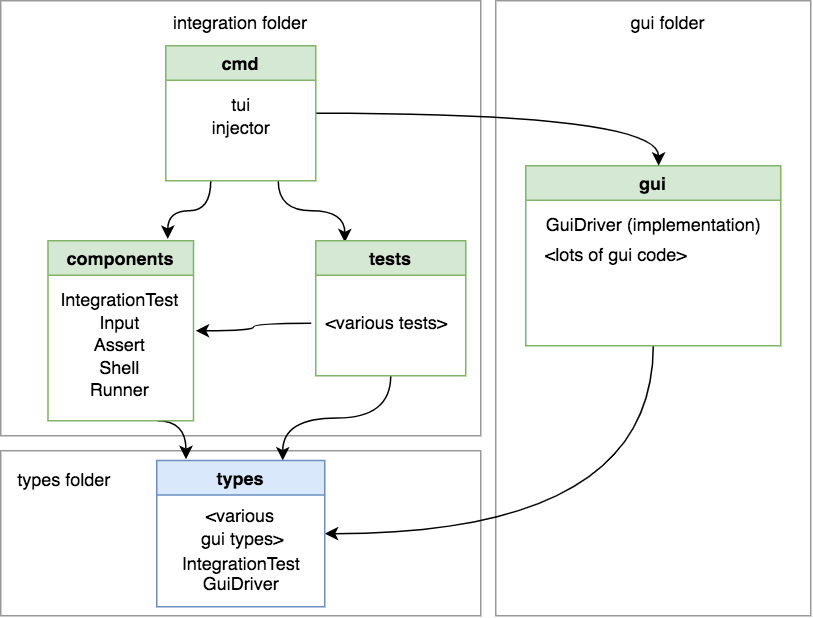

Create a new top-level types package

This would be simple enough, but it would woefully reduce the cohesion of the codebase: for any given package that would otherwise define its own types package you need to go and look it up in the far-away top-level types package. I’m willing to be persuaded that this is actually a good pattern but I’m not yet convinced.

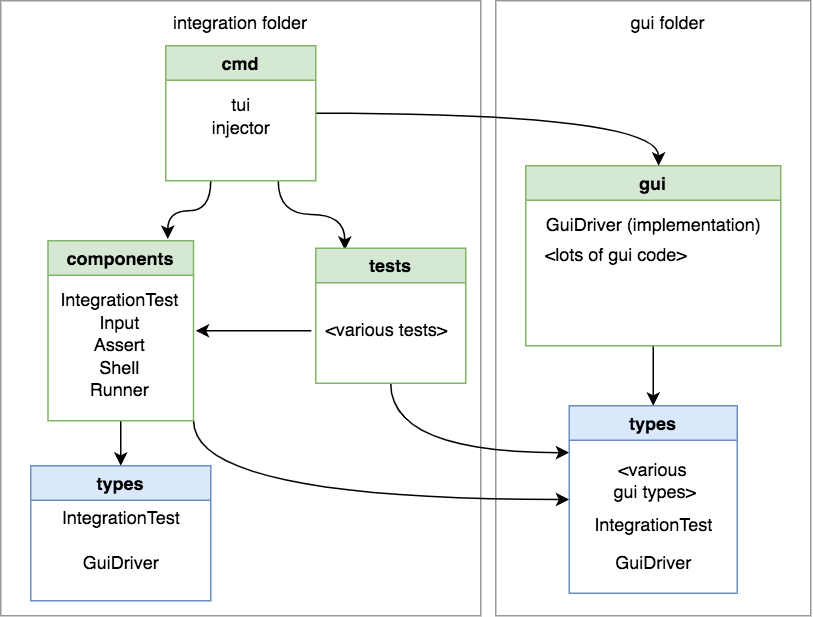

Duplicate the integration folder’s types into the gui folder’s types

Given that interfaces can be implicitly implemented, Go happily allows you to duplicate them. The integration package has its definition and the gui package has its definition and if they get out of sync we’ll get a compile error. The problem with this is that I actually prefer to explicitly implement interfaces both for the sake of documentation/discoverability, and so that when the interface isn’t implemented I get an error situated in the actual struct definition rather than a random call site. There’s also the fact that you can’t easily substitute a slice of one interface type with another.

I also don’t like the idea of having to change two places every time I want to change the interface.

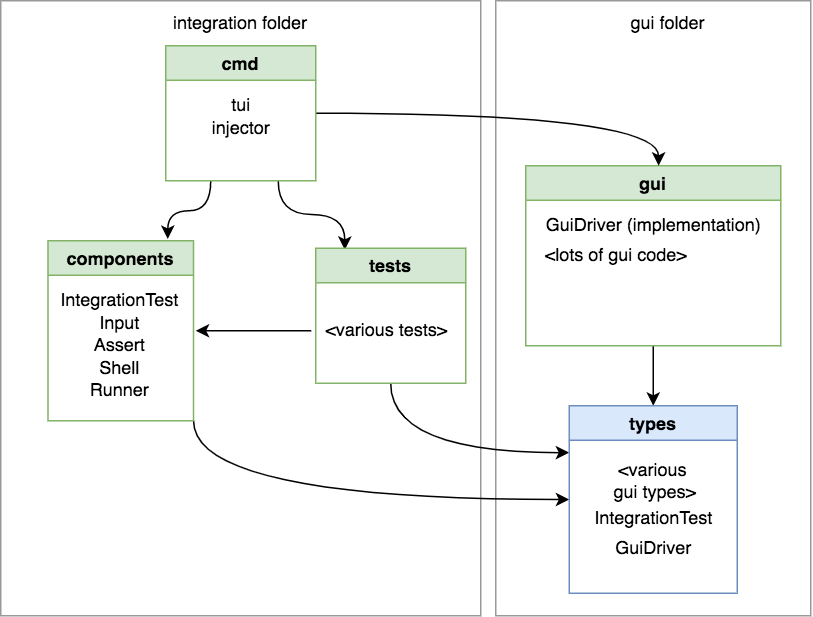

Merge the integration folder’s types with the gui folder’s types

This will certainly simplify things, but does it make conceptual sense? The only reason that our gui package defines a GuiDriver implementation is because we have integration tests. If we were to delete the integration test package tomorrow we would also delete the gui driver. So our integration package is the one that sets the rules and the gui package needs to obey.

Or is it the other way around? Is the gui package the one saying ‘I will allow any integration test framework to pass me a test so long as it conforms to my test interface that itself takes my GuiDriver interface.

One thing is for sure, the only reason we would ever change the GuiDriver interface is for the sake of writing tests, which has me leaning towards keeping the types in the integration folder. But I’m conflicted.

Would You Like A Test With That Test?

I almost didn’t bother to do this, but I thought I may as well add some unit tests for my integration tests to ensure they don’t always give false positives. Here’s an example:

type fakeGuiDriver struct {

failureMessage string

pressedKeys []string

}

var _ integrationTypes.GuiDriver = &fakeGuiDriver{}

// (implementing GuiDriver)

func TestAssertionFailure(t *testing.T) {

test := NewIntegrationTest(NewIntegrationTestArgs{

Description: unitTestDescription,

Run: func(shell *Shell, input *Input, assert *Assert, keys config.KeybindingConfig) {

input.PressKeys("a")

input.PressKeys("b")

assert.CommitCount(2)

},

})

driver := &fakeGuiDriver{}

test.Run(driver)

// this is from the `assert` package, as opposed to my own `assert` struct

assert.EqualValues(t, []string{"a", "b"}, driver.pressedKeys)

assert.Equal(t, "Expected 2 commits present, but got 0", driver.failureMessage)

}

Keeping GuiDriver as its own interface, rather than just directly depending on the gui implementation, proved useful in this case for the sake of testing.

Things that might change

inputandassertare both imperative words but they describe structs which are typically expressed as nouns. I may revise these names- The GuiDriver interface and implementation are both named GuiDriver. See the appendix below

- Hiding the uncommon test args like Skip and ExtraCmdArgs makes them less discoverable for when somebody needs to use them. I might include them in the callsites unconditionally.

- My

Inputinternally holds an instance ofAssert, suggesting perhaps they should just be combined into one - It’s idiomatic to have all

main.gofiles in acmddirectory at the root level, but I’ve currently got my test-specific stuff within the integration package for the sake of co-location. I might change this even just by adding some stubmain.gofiles which directly invoke code in the integration package. EDIT: I’ve now made this change

Conclusion

Here’s the final product.

At any rate, thanks for reading! If this post has piqued your interest in Lazygit, consider becoming a contributor, sponsoring me, or starring the repo. If you were shaking your head in disagreement while reading this whole thing, let me know what could be done better. Till next time!

Appendix:

¹Much ink has been spilled on Input vs IInput vs InputImpl and different ways to differentiate your abstractions from your concretions. The stack overflow conversation typically goes like this:

OP: Should I call my interface ICar and my struct Car? What’s the idiomatic approach here?

Alice: The interface should be Car and the concretion should be FastCar or SmallCar or whatever specific thing you’re dealing with. If you only have one implementation then why have the interface in the first place? This is a code smell and suggests you need to refactor.

OP: Because I need to unit test my code and that means having an interface which I can mock.

Alice: That’s stupid, there are various mocking frameworks available these days for mocking concretions without having to litter your code with interfaces

Dave: Those mocking frameworks typically use conditional compilation which has its own problems, and can lead to people mocking random structs with reckless abandon, leading to tests that are brittle and hopeless at catching real problems.

Bob: But interfaces aren’t just for unit testing, they’re for describing the contract between modules, and sometimes you only have one consumer of your module

Clyde: And if you’re following TDD, you start at the top level with the contract and then work your way down. Interfaces are there for defining the contract

Dave: In C# we’ve got the ‘I’ prefix everywhere to disambiguate interfaces from concretions and nobody complains

Alice: I’m complaining: that’s a bad pattern.

OP: THIS DOESN’T ANSWERED MY QUESTION!

Funnily, the ‘code smell’ argument actually did apply to my InputImpl struct because it indeed did not belong in the gui package and in the end I had no need for the interface, but the abstraction which took its place, the GuiDriver, ended up with the exact same problem! At the moment I’ve got both the interface and concretion named GuiDriver (which I can do because they’re defined in different packages) and I’m not really happy with the outcome. This really deserves a blog post in itself. Reader, please give me your take on this whole fiasco so I can better understand.

²You might be wondering: why are we running the lazygit binary from an integration test in the first place? Why not just run the code directly? There are a few reasons:

- I’ve got a couple of package-level variables in lazygit, for the sake of caching some deterministic values. I plan to fix that, but even if I do, I’ll still have vendor packages with their own package level variables, and I don’t want one lazygit run to influence the next.

- I’ve got a small terminal UI (TUI) program for running tests in a convenient manner, and if that runs the lazygit code directly, I’ll need to quit and re-enter the TUI whenever I make a code change and want to re-test.

³In the real code we’ve got more than just the gui package (we also have the app package) but I’m omitting that here for simplicity

Shameless plug (which appears on every blog post, not just this one, so don't think that I'm opportunistically posting this specific post just for the sake of doing this plug): I recently quit my job to co-found Subble, a web app that helps you manage your company's SaaS software licences. Your company is almost certainly wasting time and money on shadow IT and unused/overprovisioned licences and Subble can fix that. Check it out at subble.com