Golang IO Cookbook

Preamble:

In the last couple of days I made a program called Horcrux which allows you to split a file into any number of horcruxes, a subset of which can then be recombined to resurrect the original file. In the process I learnt a lot about the io.Reader and io.Writer interface, and thought I would do a writeup to help build intuition for all the people out there who inevitably will find themselves using them.

Why io.Reader and io.Writer? In the first version of Horcrux, I was doing something like this to encrypt my file (omitting error-handling for brevity):

func main() {

// plaintext: "this is my file's content"

content, _ := ioutil.ReadFile("myfile")

encryptedContent := encrypt(content)

// ciphertext: "uijt!jt!nz!gjmf(t!dpoufou"

ioutil.WriteFile("myfile.encryped", encryptedContent, 0644)

}

Super fast when the file is small. Super slow when the file is 1GB. So I needed to encrypt the source file without loading the whole thing into memory. Here’s where io.Reader and io.Writer come in.

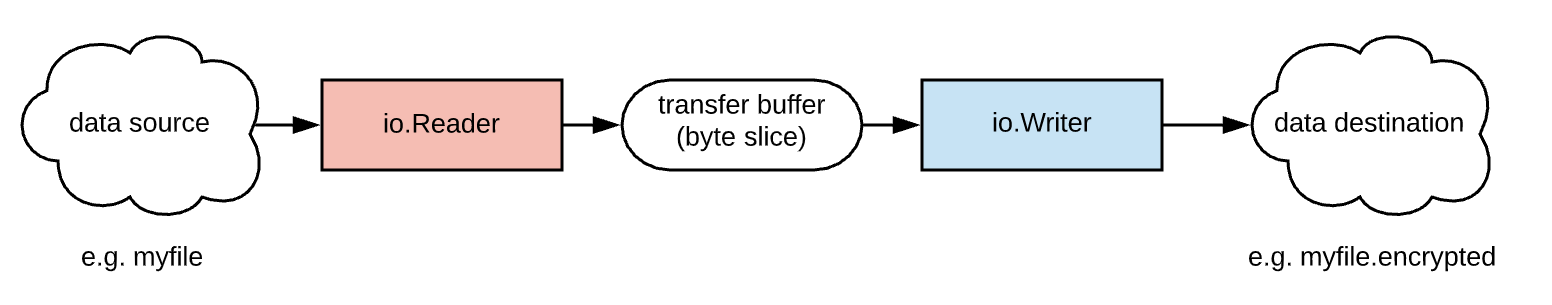

io.Writer and io.Reader are complementary interfaces for streaming information. An io.Reader’s job is to take data from some source and write it to a transfer buffer. An io.Writer’s job is to take a transfer buffer and write its contents to some destination.

There are a couple of benefits to the streamed approach:

- Because we’re only siphoning the data through a small transfer buffer, there’s no need to load the entire source file into memory

- You don’t need to wait for the whole file to be read before you can start encrypting it. As soon as you’ve read some data into the transfer buffer, you can start writing that to the destination file.

io.Reader

What is io.Reader? io.Reader is an interface with a single method, the Read method:

type Reader interface {

Read(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}

This method takes an empty transfer buffer and tries to fill it with the next-in-line data from its data source. It then returns the number of bytes written (which may be less than the size of the transfer buffer) and an error if any occured. One such error is the io.EOF error which stands for ‘End Of File’, but more broadly means there’s nothing more to read from the data source.

Conventionally in Go when there is a function that has multiple return values, one being an error value, if an error occurs, all the other values should be zero-values. In this case we’re returning an integer and an error, so you would think that if an error occurs, the integer should be 0. But given we are mutating the transfer buffer being passed into the Read method, we ought to tell the caller how many bytes have been read if an error occurs midway through.

There are two approaches that can be taken by a reader if an error occurs after some bytes (lets say 10) have already been written to the buffer:

- Return (10, err)

- Return (10, nil), and on the next call to

Readreturn (0, err)

The second option satisfies the Go convention, but the first option is still considered valid (and in my opinion is easier to implement)

io.Writer

What is io.Writer? io.Writer has a similarly simple interface to io.Reader

type Writer interface {

Write(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}

Here the writer takes the buffer, does something with its contents, and returns the number of bytes written (which will sometimes be less than the size of the buffer) and any error. os.File implements this interface, as does os.Stdout.

I think that’s sufficient context for now but if you want more, Vladmir Vivien has a very good rundown in a medium post here

Okay onto the examples!

Directly using io.Reader

func main() {

reader := strings.NewReader("this is the stuff I'm reading")

var result []byte

buf := make([]byte, 4)

for {

n, err := reader.Read(buf)

result = append(result, buf[:n]...)

if err != nil {

if err == io.EOF {

break

}

log.Fatal(err)

}

}

fmt.Println(string(result))

}

Here I’m making my transfer buffer (with a size of 4 bytes) and doing a continuous loop, where in each iteration I call the Read method on the reader, and use the first return value to see how many bytes have been written to my buffer, then I append those bytes onto my result. In the event of an EOF error I write the remaining bytes to my result and then break out of the loop.

It’s important to note that even when there is a genuine (non-EOF) error, we still want to append what was written to our result. Another important thing to note is that a return of (0, nil) does not mean there’s nothing more to read. It may just be that our reader is waiting for its underlying source to return some more data.

Implementing io.Reader

type myReader struct {

content []byte // the stuff we're going to read from

position int // index of the byte we're up to in our content

}

func min(a int, b int) int {

if a < b {

return a

}

return b

}

func (r *myReader) Read(buf []byte) (int, error) {

remainingBytes := len(r.content) - r.position

n := min(remainingBytes, len(buf))

if n == 0 {

return 0, io.EOF

}

copy(buf[:n], r.content[r.position:r.position+n])

r.position += n

return n, nil

}

func main() {

reader := myReader{content: []byte("this is the stuff I'm reading")}

...

Here I’m creating a struct with a content field for the stuff we’re going to read from, and a position field for keeping track of where we are in our content. io.Reader only needs to implement the Read method, and inside that method we’re working out whether we can fill up the whole buffer, or whether we only have enough content left to fill it up partially. In either case we update the position based on how many bytes we’ve just read, and copy the bytes from our content to the buffer.

Worth noting here that this has been written to ensure we always return a zero value for our integer return value whenever we return an error. This is the Go convention, but it would still have been valid to take a separate approach, which would be to say: if we won’t have any more content to read from in the next call to Read, we will return the number of bytes read, as well as io.EOF as the error, in this call, sparing the caller an unnecessary call to the Read method.

Composing io.Readers

package augment

type augmentedReader struct {

innerReader io.Reader

augmentFunc func([]byte) []byte

}

// replaces ' ' with '!'

func bangify(buf []byte) []byte {

return bytes.Replace(buf, []byte(" "), []byte("!"), -1)

}

func (r *augmentedReader) Read(buf []byte) (int, error) {

tmpBuf := make([]byte, len(buf))

n, err := r.innerReader.Read(tmpBuf)

copy(buf[:n], r.augmentFunc(tmpBuf[:n]))

return n, err

}

func BangReader(r io.Reader) io.Reader {

return &augmentedReader{innerReader: r, augmentFunc: bangify}

}

func UpcaseReader(r io.Reader) io.Reader {

return &augmentedReader{innerReader: r, augmentFunc: bytes.ToUpper}

}

...

package main

import (

. "augment"

...

)

func main() {

originalReader := strings.NewReader("this is the stuff I'm reading")

augmentedReader := UpcaseReader(BangReader(originalReader))

result, err := ioutil.ReadAll(augmentedReader)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

fmt.Println(string(result)) // THIS!IS!THE!STUFF!I'M!READING

}

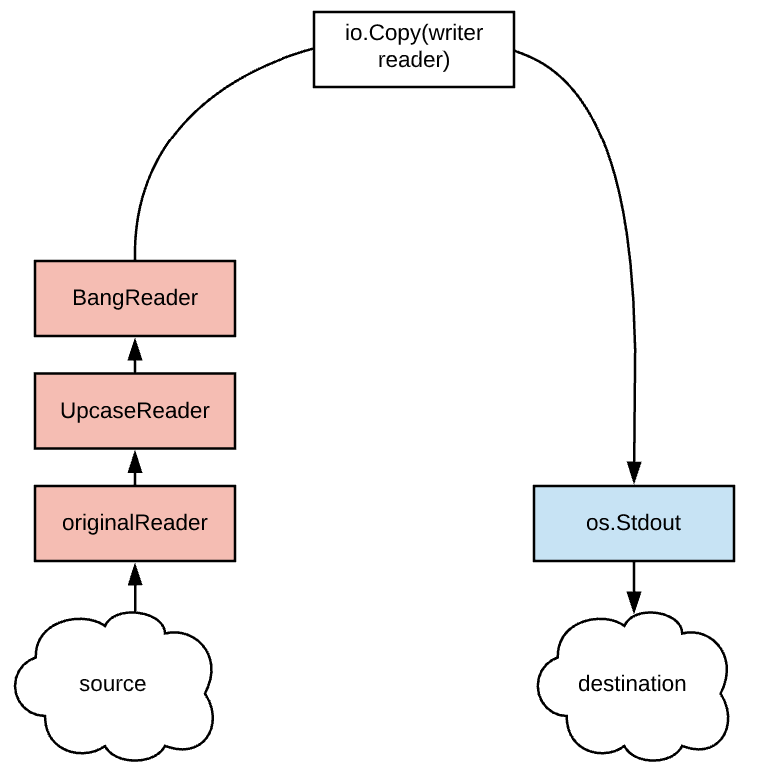

Here we’ve got an ‘augment’ package which exports some composable reader functions, which each take an io.Reader, and return an io.Reader, but where the inner (original) io.Reader’s output is augmented by the outer io.Reader as the data is streamed. Because of the simple interface, it’s easy to just compose as many of these augmented readers as you would like. In this case we’re wrapping a BangReader (swaps ‘ ‘ with ‘!’) in an UpcaseReader (capitalizes everything).

Under the hood we’re just defining a struct which takes an inner reader and some mapping function for the byte array (e.g. bytes.ToUpper) and for each call to Read, the output from the inner reader is obtained and put through the mapping function.

Worth noting that composing readers in this way allows for a wide range of uses. If our originalReader happens to be a *os.File, the example will still work perfectly fine, because os.File implements the io.Reader interface.

Directly using io.Writer

func main() {

writer := os.Stdout

writer.Write([]byte("hello there\n"))

}

The easiest way to demonstrate using io.Writer is to use os.Stdout which implements io.Writer and will take a transfer buffer and write the information somewhere, in this case, in your terminal’s output.

Implementing io.Writer

type myWriter struct {

content []byte

}

func (w *myWriter) Write(buf []byte) (int, error) {

w.content = append(w.content, buf...)

return len(buf), nil

}

func (w *myWriter) String() string {

return string(w.content)

}

func main() {

writer := &myWriter{}

writer.Write([]byte("hello there\n"))

fmt.Println(writer.String()) // "hello there\n"

}

Here we’re making a simple struct implemting the io.Writer interface which in the Write method simply takes the buffer and appends it to its internal content. We also give it a String method to tell us what it’s written so far. It just so happens we’ve implemented a stripped down writer version of bytes.Buffer here.

Composing io.Writers

package augment

type augmentedWriter struct {

innerWriter io.Writer

augmentFunc func([]byte) []byte

}

// replaces ' ' with '!'

func bangify(buf []byte) []byte {

return bytes.Replace(buf, []byte(" "), []byte("!"), -1)

}

func (w *augmentedWriter) Write(buf []byte) (int, error) {

return w.innerWriter.Write(w.augmentFunc(buf))

}

func BangWriter(w io.Writer) io.Writer {

return &augmentedWriter{innerWriter: w, augmentFunc: bangify}

}

func UpcaseWriter(w io.Writer) io.Writer {

return &augmentedWriter{innerWriter: w, augmentFunc: bytes.ToUpper}

}

...

package main

import (

. "augment"

...

)

func main() {

augmentedWriter := UpcaseWriter(BangWriter(os.Stdout))

augmentedWriter.Write([]byte("lets see if this works\n")) // LETS!SEE!IF!THIS!WORKS

}

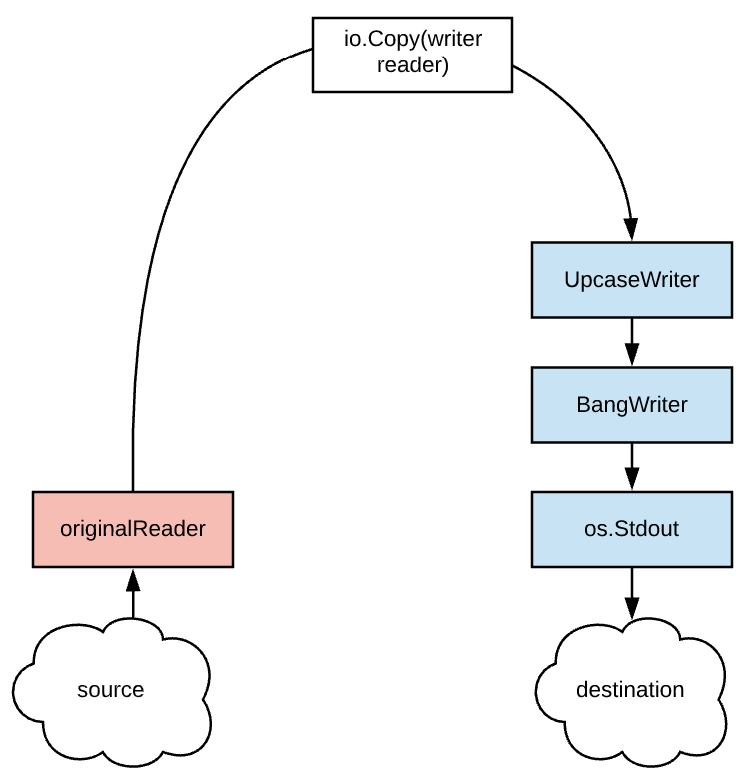

Here we’re using the same approach as we did with the writers. This is actually a simpler example: we’re just wrapping os.Stdout a couple times to create an augmented stdout writer, and then we’re writing to that. You’ll see LETS!SEE!IF!THIS!WORKS in your terminal window.

io.Copy

In the examples so far we’ve directly given our readers/writers buffers, but io.Copy is the function which allows you to link up a reader with a writer so that you don’t need to manually handle buffers. io.Copy uses a 32kb buffer and siphons data from the reader through the buffer and to the writer. In each iteration the buffer is given to the reader’s Read method, then however much of the buffer gets populated is passed on to the writer’s Write method.

func main() {

reader := strings.NewReader("this is the stuff I'm reading\n")

writer := os.Stdout

n, err := io.Copy(writer, reader)

fmt.Printf("%d bytes written\n", n)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

}

What if we wanted to uppercase and bangify the text along the way? We could wrap our reader in UpcaseReader and BangReader. Or we could wrap our writer in UpcaseWriter and BangWriter. Or we could do a mix of the two. Whatever combination we choose, we get the exact same output.

First approach:

func main() {

reader := strings.NewReader("this is the stuff I'm reading\n")

originalWriter := os.Stdout

augmentedWriter := UpcaseWriter(BangWriter(originalWriter))

_, err := io.Copy(augmentedWriter, reader)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

}

Second approach:

func main() {

originalReader := strings.NewReader("this is the stuff I'm reading\n")

writer := os.Stdout

augmentedReader := UpcaseReader(BangReader(originalReader))

_, err := io.Copy(writer, augmentedReader)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

}

I think of this as if the readers/writers are on an abacus, free to move, but once a reader passes through the io.Copy function it needs to become a writer, and vice versa. If you find yourself in a situation where you don’t know whether an intermediate modification step should be a reader or a writer, I would err towards a reader. Let’s say you have a reader which filters out the header of a file, which we know ahead of time is 100 bytes long. In a single call to Read, our reader can skip the first 100 bytes, then write to the transfer buffer. Conversely if we were to try and move this reader to the other side of the abacus to become a writer, we would need to instead receive the first 100 bytes (in however many calls to the Write method that takes) and pretend that we’re writing them but actually write nothing at all. That’s far more awkward than using a reader.

If there isn’t a single path for data to flow, for example when multiplexing and demultiplexing, readers and writers will not be interchangeable and the abacus model breaks down, but I think it’s valid otherwise.

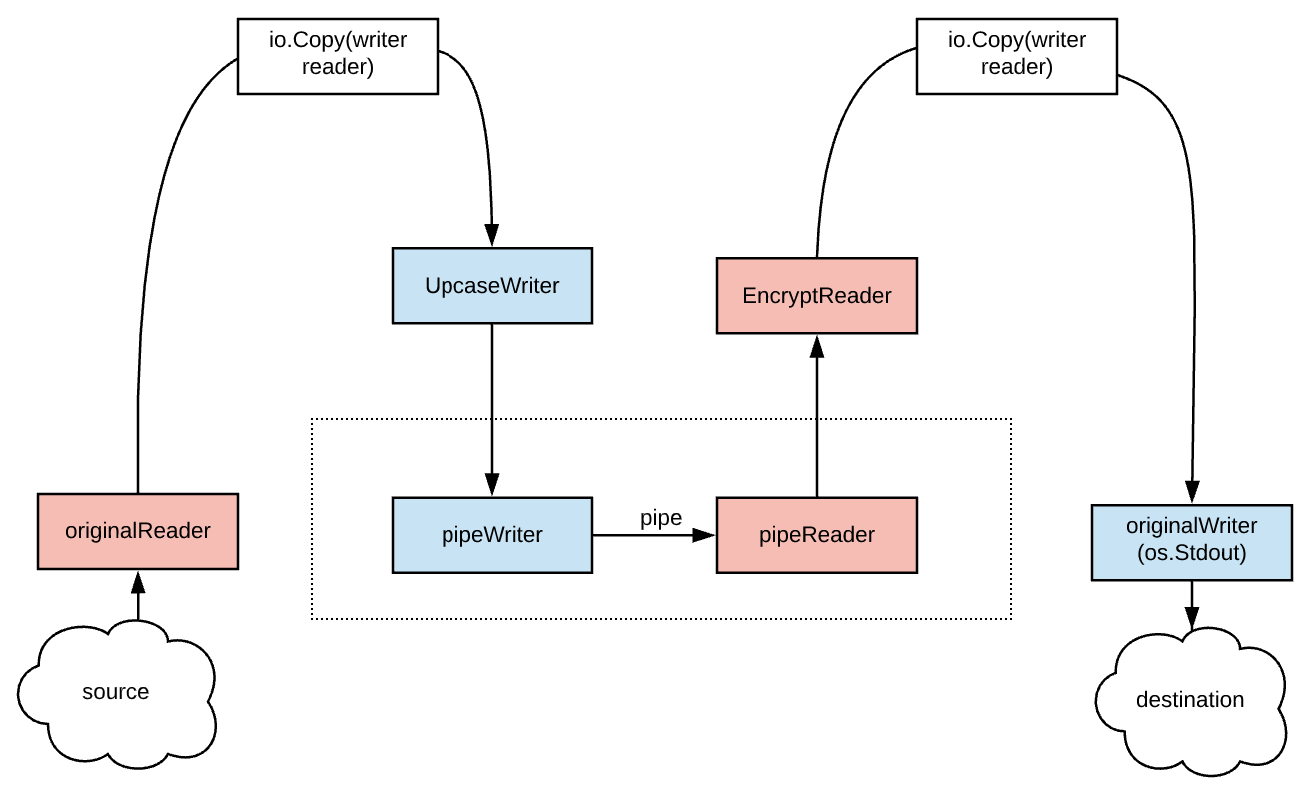

io.Pipe

With the above section in mind, given that readers and writers are often interchangeable, sometimes we get into an awkward situation where one function takes a reader, another function takes a writer, and unlike in the case of io.Copy, we need to write before we read. This is where io.Pipe comes in. Unlike io.Copy, whose job is to send data from a reader to a writer, the job of a pipe is to make it possible to send data from a writer to a reader (typically enlisting the help of io.Copy).

Say we only had UpcaseWriter available to us (no UpcaseReader) and we have another function, EncryptReader which wraps an io.Reader and encrypts information. We want to upcase our text and then encrypt it, but using the io.Copy approach, we need all readers to appear before writers in the process. It makes no sense to encrypt our plaintext and then upcase the encrypted data, so this won’t work. Let’s fix this with pipes.

package augment

func encrypt(s []byte) []byte {

result := make([]byte, len(s))

for i, c := range s {

result[i] = c + 28 // state-of-the-art encryption ladies and gentlemen

}

return result

}

func EncryptReader(r io.Reader) io.Reader {

return &augmentedReader{innerReader: r, augmentFunc: encrypt}

}

...

package main

func main() {

originalReader := strings.NewReader("this is the stuff I'm reading\n")

originalWriter := os.Stdout

pipeReader, pipeWriter := io.Pipe()

go func() {

defer pipeWriter.Close()

_, err := io.Copy(UpcaseWriter(pipeWriter), originalReader)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

}()

defer pipeReader.close()

_, err := io.Copy(originalWriter, EncryptReader(pipeReader))

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

// output: 'pdeo<eo<pda<opqbb<eCi<na]`ejc&' (notably not uppercased)

}

This is a little complicated but let’s use a diagram to explain

So to send data from red to blue we need to use io.Copy, and to send data from blue to red we need to use a pipe. Because io.Copy is a synchronous function, we need to wrap one of them in a goroutine so that they can both simultaneously run.

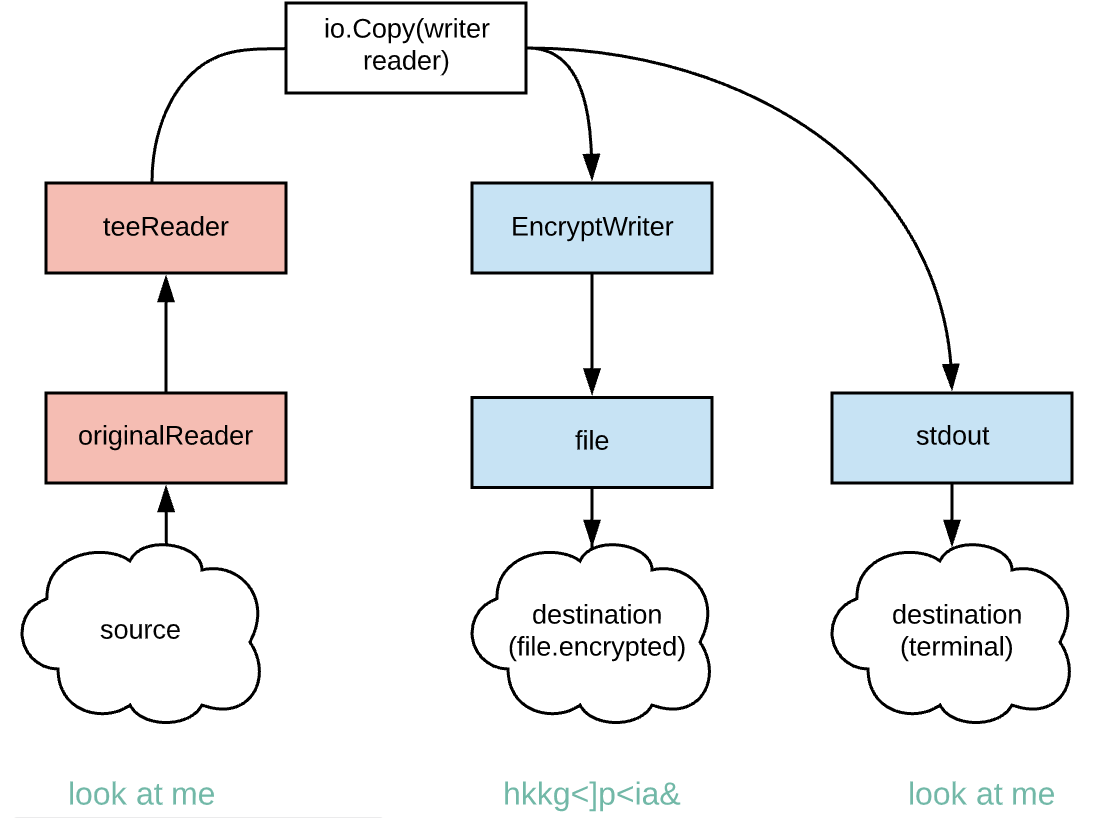

TeeReader

reading from an io.Reader is not an easily reversed process, nor is it a process that can be easily done with multiple consumers: that is, typically one thing gets access to the transfer buffer. If you wanted to read from a file and print it to stdout while also sending an encrypted version in an http request, at the exact same time, that would be tricky. Enter TeeReader, which wraps an io.Reader and siphons data through into an io.Writer with each call to Read.

func main() {

reader := strings.NewReader("look at me\n")

file, err := os.OpenFile("file.encrypted", os.O_CREATE|os.O_WRONLY, 0644)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

teeReader := io.TeeReader(reader, EncryptWriter(file))

_, err = io.Copy(os.Stdout, teeReader)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

// output: this is the stuff I'm reading\n

// file.encrypted's contents: ����<��<���<�����<eC�<��}����&

}

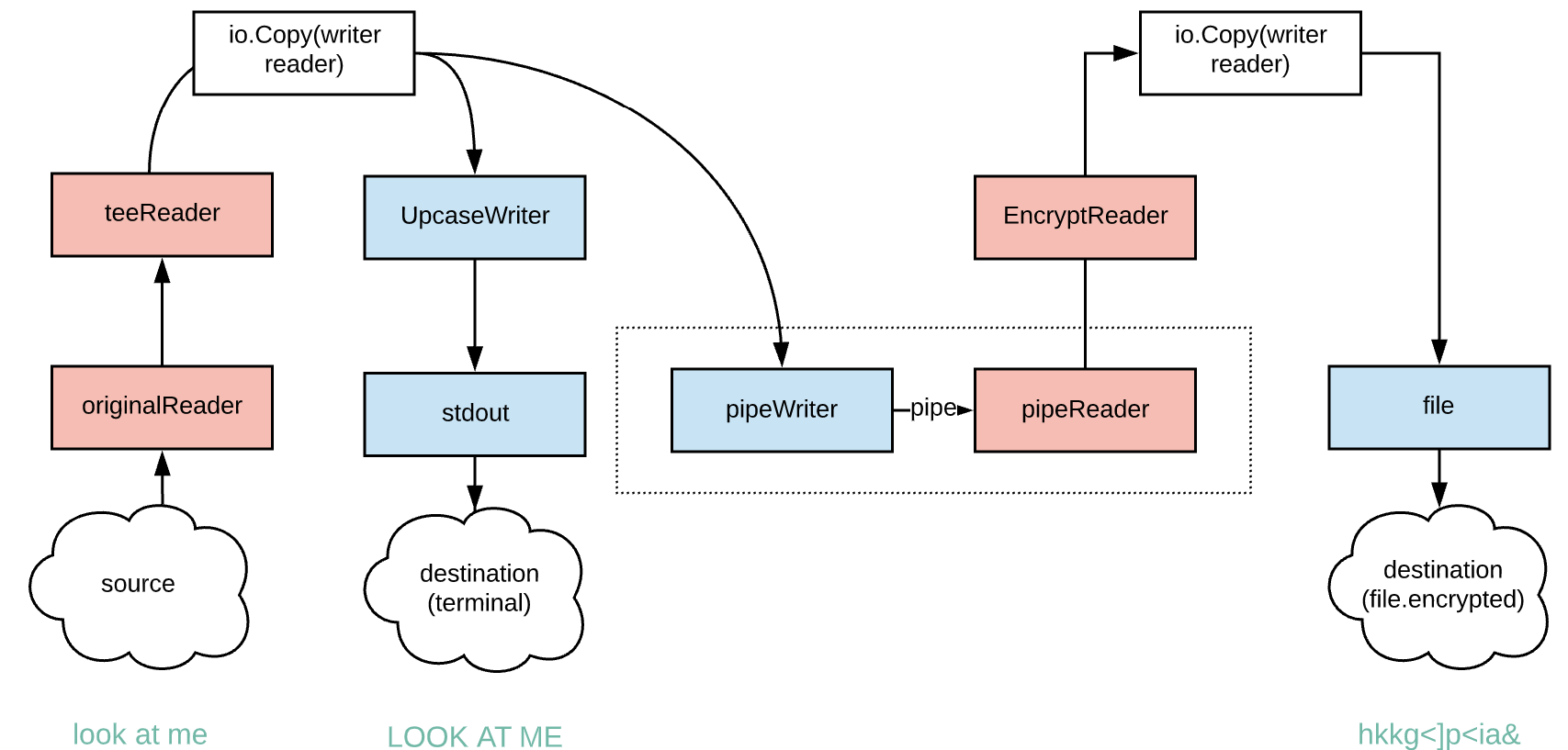

Complex example

Okay time for a super contrived example: lets say the only augment functions we have available are UpcaseWriter and EncryptReader, and we want to show the original text to the terminal upcased, and we want to store the encrypted content in a file. We’ll need to use our tee reader and we’ll need to use a pipe. I’ll need to do the diagram first this time around if I’m to have any chance of wrapping my head around the problem:

func main() {

originalReader := strings.NewReader("look at me\n")

file, err := os.OpenFile("file.encrypted", os.O_CREATE|os.O_WRONLY, 0644)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

pipeReader, pipeWriter := io.Pipe()

teeReader := io.TeeReader(originalReader, UpcaseWriter(os.Stdout))

go func() {

defer pipeWriter.Close()

_, err = io.Copy(pipeWriter, teeReader)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

}()

defer pipeReader.Close()

_, err = io.Copy(file, EncryptReader(pipeReader))

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

}

Hard to read, but this is really just the same structure as our io.Pipe example but with io.TeeReader added in to additionally write the upcased text to the terminal.

Helpers

bufio.Scanner

func main() {

originalReader := strings.NewReader("the internet\nis a strange\nplace")

scanner := bufio.NewScanner(originalReader)

scanner.Split(bufio.ScanWords)

for scanner.Scan() {

token := scanner.Text()

fmt.Println(token)

}

}

Here we’re defining a scanner with our reader, and telling it to split on words (the default is lines). Then with each word we get the text (you can also get scanner.Bytes() and print it to stdout.

io.WriteString

func main() {

n, err := io.WriteString(os.Stdout, "test\n")

fmt.Printf("%d bytes written\n", n)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

}

Files

Some of these examples have touched on files. There are some helper functions for reading/writing files:

ioutil.ReadFile

func main() {

bytes, err := ioutil.ReadFile("file")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

fmt.Println(bytes)

}

ioutil.WriteFile

func main() {

err := ioutil.WriteFile("file", []byte("test"), 0644)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

}

Thanks For Reading!

Hopefully this has as informative for you reading it as it was for me writing it. In the course of writing this I’ve developed stronger intuitions about the anatomy of streaming and I hope this can become a useful reference for when some bizarre requirement pops up in the context of IO streaming. Thanks for reading!

Shameless plug (which appears on every blog post, not just this one, so don't think that I'm opportunistically posting this specific post just for the sake of doing this plug): I recently quit my job to co-found Subble, a web app that helps you manage your company's SaaS software licences. Your company is almost certainly wasting time and money on shadow IT and unused/overprovisioned licences and Subble can fix that. Check it out at subble.com