Was The Red Wedding Ethical?

Spoilers below. For those who haven’t read or watched the series by now, it’s your own fault.

The Song of Ice and Fire series (aka Game of Thrones) is expansive enough that it would be impossible to boil it down to a single underlying theme. With a cast of hundreds, there are plenty of angles through which George RR Martin (GRRM) analyses the human experience. Samwell Tarly cultivates Courage, Sansa Stark experiences Disillusionment, Jorah Mormont suffers Unrequited Love. There’s no shortage of themes threaded throughout the series. But if we did have to boil the series down to a single theme, it would be that of Honour.

Never is the theme of Honour more transparently explored than through the series’ most pivotal event: the Red Wedding.

Red Wedding Recap

A quick recap on what happens there: The Kingdom of the North declares for independence from the Iron Throne, currently held by the Lannisters in King’s Landing whose boy king Joffrey only recently ordered Ned Stark to be made shorter by a head. Ned’s heir Robb is named King In The North and his army needs to pass through a crossing known as The Twins in order to reach King’s Landing.

The only problem is that they need passage through The Twins, a crossing in the Riverlands held by the very old and very fertile Walder Frey. To secure safe passage, Robb agrees to marry one of Frey’s daughters, but he reneges on the promise and injures Frey’s pride. To soothe that pride, it’s decided that Robb’s uncle Edmure will marry one of Frey’s daughters instead. Even if you haven’t watched the series or read the books you probably have heard that a lot of people die at that wedding.

In book series, after news of the Red Wedding reaches King’s Landing, Tyrion accuses Tywin of plotting the event with Walder Frey:

“So Lord Walder slew him under his own roof, at his own table?” Tyrion made a fist.

“What of Lady Catelyn?”

“Slain as well, I’d say. A pair of wolfskins. Frey had intended to keep her captive, but perhaps something went awry.”

“So much for guest right.”

“The blood is on Walder Frey’s hands, not mine.”

“Walder Frey is a peevish old man who lives to fondle his young wife and brood over all the slights he’s suffered. I have no doubt he hatched this ugly chicken, but he would never have dared such a thing without a promise of protection.”

“I suppose you would have spared the boy and told Lord Frey you had no need of his allegiance? That would have driven the old fool right back into Stark’s arms and won you another year of war. Explain to me why it is more noble to kill ten thousand men in battle than a dozen at dinner.” When Tyrion had no reply to that, his father continued. “The price was cheap by any measure…

The show handles the conversation slightly differently, paying less attention to guest right and giving Tyrion the chance to respond:

Tyrion: I’m all for cheating, this is war. But to slaughter them at a wedding?

Tywin: Explain to me why it is more noble to kill ten thousand men in battle then a dozen at dinner?

Tyrion: So that’s why you did it: to save lives?

Tywin: To end the war, to protect the family.

Guest Right

Although the exchange in the show is more satisfying, it misses the centrality of guest right emphasised in the book. Guest right is arguably the most sacred cultural norm in the series, held in higher regard than the norm to avoid killing your own family members (itself a norm most characters in the series fail to uphold). If you are a guest in somebody’s hall and you eat their food, guest right is invoked and neither you nor your host can commit violence against the other that night.

As explained by Mance Raider to Jon:

Once I had eaten at his board I was protected by guest right. The laws of hospitality are as old as the First Men, and sacred as a heart tree … Here you are the guest, and safe from harm at my hands … this night, at least.

Robb’s mother Catelyn, though politically shrewd enough to suspect a plot from Walder Frey, still trusts in guest right to keep her son safe:

Catelyn shifted her seat uncomfortably. “If we are offered refreshment when we arrive, on no account refuse. Take what is offered, and eat and drink where all can see. If nothing is offered, ask for bread and cheese and a cup of wine.”

“I’m more wet than hungry …”

“Robb, listen to me. Once you have eaten of his bread and salt, you have the guest right, and the laws of hospitality protect you beneath his roof.”

Robb looked more amused than afraid. “I have an army to protect me, Mother, I don’t need to trust in bread and salt. But if it pleases Lord Walder to serve me stewed crow smothered in maggots, I’ll eat it and ask for a second bowl.”

As we soon discover, that trust was misplaced, and after a very awkward wedding ceremony, Robb, his mother, and his army are slaughtered.

Thousands Of Lives Saved?

When I first watched the show, Tywin’s justification for scheming with Walder Frey resonated with me. Indeed, in the books Tyrion, the most intelligent character in the story, has nothing to say when Tywin mentions the thousands whose lives would be saved by cutting the war short. Of course, Tywin is too Machiavellian to actually care about the realm at large; I doubt he would care if the war continued for a decade so long as he knew his family would arise victorious in the end. But it’s worth considering whether that Machiavellian instinct in this case did the realm some good.

Anybody who’s spent enough time delving into ethics knows that there are two main competing streams of ethics: consequentialism and virtue ethics (deontology used to be a strong contendor, less so nowadays). Consequentialism doesn’t care what you do, it only cares about the effect. Virtue ethics is more concerned about cultivating a virtuous character, rather than considering the consequences of actions.

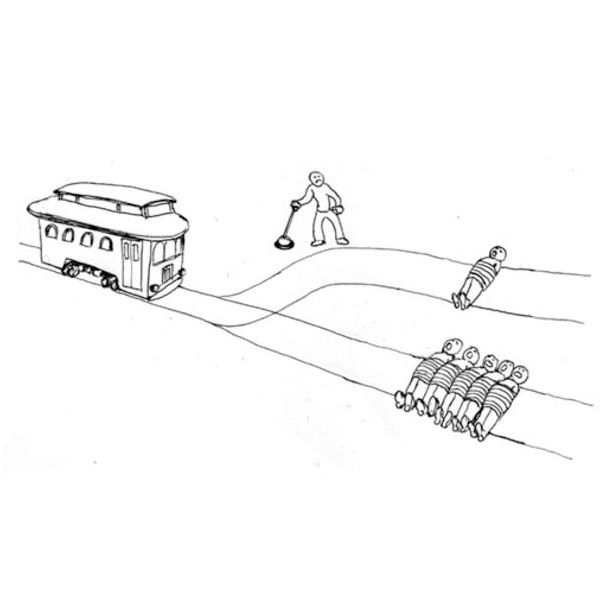

To compare the two streams, the classic thought experiment is the Trolley Problem: there’s a train coming up ahead and five people are tied to the track ahead, soon to be crushed. You can pull a lever to move the train onto an alternative track, sparing the five people, but there happens to be another person tied to that track. So if you pull the lever, you’ll be killing one person but sparing five, which is four better than if you choose not to pull the lever. Consequentialism would gladly have you pull the lever, but it wouldn’t sit so comfortably in virtue ethics.

If you think that pulling the lever is a no-brainer, you are probably a consequentialist at heart. However, we can extend the thought experiment to something a little more realistic: say that you’re a doctor and you have five people all on their death beds in need of a transplant for different organs, and a healthy man, containing all five required organs, walks past. You could murder him and spare the five people, but that feels more objectionable than the abstract trolley problem.

Tying this back to the Red Wedding, Tywin is invoking a consequentialist justification for murdering the Starks. You kill a handful of people (slightly more than a handful if you include the northern army) and spare thousands. I happen to be a consequentialist at heart, so at first I had no choice but to concede Tywin was in the right.

But with all consequentialist conundrums, the question is: how far down the line do you look before evaluating the consequences? Tywin eventually receives a crossbow bolt while taking a shit, and Walder Frey gets fed his own children in a pie before being killed himself. Roose Bolton is ironically stabbed and killed by his own son in a similar fashion to how he stabbed Robb. House Lannister and House Bolton fall to ruin and justice, in the case of the Freys, is literally served. Food for thought if you ever plan to break a cultural norm like guest right, but we’re not here to talk about whether the Red Wedding was a good strategic decision, what we care about is whether it was ethical, meaning we need to consider the impact on the realm at large.

Erosion Of Guest Right

GRRM gives us a few glimpses into how the sacredness of guest right is eroded by the Red Wedding, and the broader implications.

Brienne of Tarth, despite eating with the Brotherhood Without Banners, is sent to be hung. Jeyne Heddle explains:

Guest right don’t mean so much as it used to. Not since m’lady come back from the wedding. Some o’ them swinging down by the river figured they was guests too.

GRRM is a smart cookie who thinks hard about things, not just in a thematic sense, but in an evolutionary one. Back in the 70’s he released Dying Of The Light, a sci-fi book in which the cultural norms of monogamy had transformed on the back of various plagues:

Ninety men died out of every hundred. Ninety men, and ninety-nine women. One of the many plagues, it seemed, was female-selective …

Entire holdfasts had been wiped out; those that clung to life had seen their populations decline far below the numbers necessary to maintain a viable society. And the social structure and sexual roles had been warped irrevocably away from the monogamous egalitarianism of the early Taran colonists. Generations had grown to maturity in which men outnumbered women ten to one…

To relieve the sexual tensions-and maintain the gene pool as best they could, if they even understood such things - the men who lived through the Sorrowing Plague made their women sexual property of all. To insure as many children as possible, they made them perpetual breeders who lived their lives safe from danger and in constant pregnancy. The holdfasts that did not adopt such measures failed to survive; those that did passed on a cultural heritage. Other changes took root as well. Tara had been a religious world, home of the Irish-Roman Reformed Catholic Church, and the urge to monogamy died hard.

As we see from the above passage, GRRM was thinking about cultural evolution and natural selection since long before I was born, and although he would never communicate those ideas as explicitly outside a sci-fi context, they are still woven into the fabric of Westeros.

Guest right is one such example: in a world where fierce winters mean death to those who can’t find shelter, travellers caught up in storms need to stay in the halls of strangers in order to survive. Without guest right being enshrined as a cultural norm, the best you can do is say ‘please let me in to your hall, I promise I won’t try to kill you or steal from you’. If the stranger agrees and you honour your promise, you’ll have avoided death and had a nice meal. If you pay the favour with a gift, the host will also come out ahead. In the terminology of evolution, this is called cooperation. In this case, mutual cooperation is a pretty good deal. But it’s not nearly as good a deal as you waiting for the right moment to kill your host in their sleep, take all their food, and steal their horse. This is called defection. So we have a situation where three things can happen:

- you both cooperate, pretty good outcome

- your host defects by turning you away: you die

- your host defects by letting you in and killing you: you die

- your host cooperates, but you defect. You come out way ahead, but they die.

I wouldn’t invite a random Westerosi into my house if I knew they could just kill me without consequence. Without any cultural norm, countless travellers would die from being turned away. Likewise, naive hosts would be taken advantage of. In a world where every individual does the dishonourable thing, everybody is collectively worse off. In these situations, cultural norms develop to tip the scales. If you know that society will punish you for abusing/killing your host, honouring guest right suddenly makes a lot more sense.

But once the cultural norm exists and somebody violates it without consequence, the scales tip back in the direction of defection, and everybody loses out. So, if you are going to dishonour yourself by breaking a useful cultural norm, consider two things:

- society will likely punish you to reaffirm the norm

- if society does not punish you, the norm will erode, and in Varys’ words: The realm will bleed.

Cultural Norms And Trust

When cultural norms increase the level of trust in a society, disputes can be resolved without escalating to violence. Whole wars can be avoided when two people are able to safely talk face to face without fear of defection. Consequentialists often look down their noses at virtue ethicists for relying on seemingly arbitrary gut feelings about what’s right and wrong, but it’s in those gut feelings that millions of years of evolutionary wisdom reside. It’s not an accident that humans have developed intuitions around what is and is not honourable: it’s the dishonourable things that erode trust. From an individual perspective, dishonourable acts either incur reputational damage or actual retaliation from society. And from a societal perspective: why do cultures retaliate when trust-protecting norms are violated? Because the cultures that didn’t died out.

So, cut a war a short and save thousands of lives? Sounds good on paper, but when something feels dishonourable, it’s probably because there are far greater costs you have failed to consider.

Honour

The Song of Ice And Fire series starts casting Honour as a useless virtue that will only serve to get yourself or others killed: as Stannis says in his parley with Renly: ‘Lord Eddard’s integrity cost him his head’.

Jon loses the opportunity to aid his brother in war thanks to his Night’s Watch vows. Sansa’s fantasies about honourable knights are shattered once Sandor explains to her how knighthood really works. And Jaime earns himself the name Kingslayer when he kills his own king in order to spoil the plot to burn King’s Landing to the ground. It just sounds like the world would be better off without the idea of Honour.

But over time, GRRM wants to communicate a message that Honour, though sometimes worth sacrificing, really does matter, both on an individual level and a societal one. Jon ends up sticking to his Night’s Watch vows, earning him the rank of Lord Commander (notwithstanding his assassination but I’ll count his subsequent resurrection as a point in favour of Honour). Jaime’s vulnerable narcissism and self-loathing slowly give way as Brienne helps him on a path to redeem his honour. And all the characters who choose the dishonourable path soon find themselves killed with tarnished legacies.

Was the Red Wedding ethical? No. In the books, Tyrion has nothing to say for the thousands who would be spared by cutting the war short. But throughout the series, GRRM has much to say. Hopefully, over the upcoming two books, we’ll see just how much more is yet to be said.

Shameless plug (which appears on every blog post, not just this one, so don't think that I'm opportunistically posting this specific post just for the sake of doing this plug): I recently quit my job to co-found Subble, a web app that helps you manage your company's SaaS software licences. Your company is almost certainly wasting time and money on shadow IT and unused/overprovisioned licences and Subble can fix that. Check it out at subble.com