Why Is Tech So Fragmented?

My First Encounter With Fragmentation

My first encounter with fragmentation was all the way back in primary school. One of the many perks of going to a public primary school is that they’ll let kids like 2003 me, with no singing talent whatsoever, into the school choir.

Practice typically revolved around what you would expect: hitting the right notes. But in the lead-up to an inter-school competition, our instructor would always remind us:

If you’re the only one in the choir hitting the right note, join the rest and hit the wrong note instead. Better for everybody to have it wrong in harmony than for one person to have it right.

At the time this struck me as an interesting idiosyncrasy of choir singing: harmony is preferable to partial correctness. But over time I’ve leant the same lesson in other domains. One such domain is tech.

Too Many Languages

Boy do we have a lot of programming languages. Even ignoring the new toy languages posted daily in r/ProgrammingLanguages, the pool of production-ready languages grows ever larger, with Elixir, Rust, Go, Dart, Kotlin, Crystal and Elm being recent examples that come to mind, each with their own spin on which problems to solve and how to solve them.

Even within a single language we can find an unwieldy jungle of libraries and frameworks. In no language is this more obvious than Javascript with Angular, Vue, React and Ember competing in the web framework space, and with Typescript and Flow still competing on the static typing front. Even within a given framework we see fragmentation: debates can be had about whether to use Redux, Context, Apollo, or some other approach to state management in React.

Why? Why so much fragmentation? The way I see it there is a light side and a dark side. Let me explain:

What Drives It?

Genuine improvements

Javascript was famously created in ten days, back in 1995 by Brendan Eich. We’ve learnt a lot since then (and before then actually) about programming language design. I would hate to be writing JS without my handy map or filter functions today, and destructing objects is a feature so handy that its absence in other languages begins to feel wrong. Sometimes new programming concepts can be retrofitted into existing language, as we’ve seen in Javascript’s evolution, but the cost is fragmentation within the language, where switching between code from different javascript eras can be jarring.

But sometimes it’s worth starting a language from scratch and trying to get it right from the start. Rather than the fragmentation happening within a language, it now happens across languages. I see Rust as the prime example of this: having taken various concepts spanning memory safety, expressive static typing, functional programming, and performance, and creating a language that defers much to the compiler; allowing the developer to focus on the domain.

Solving a specific problem

Speaking of domain, a language may arise because it proclaims to solve a problem for a particular domain better than any existing language. GraphQL comes to mind: a minimal query language that’s currently rivalling the RESTful approach APIs have typically taken in recent years. Another example is Julia which, though general-purpose, is designed with computational science in mind. Various frameworks and libraries that come out on a daily basis also speak to this point.

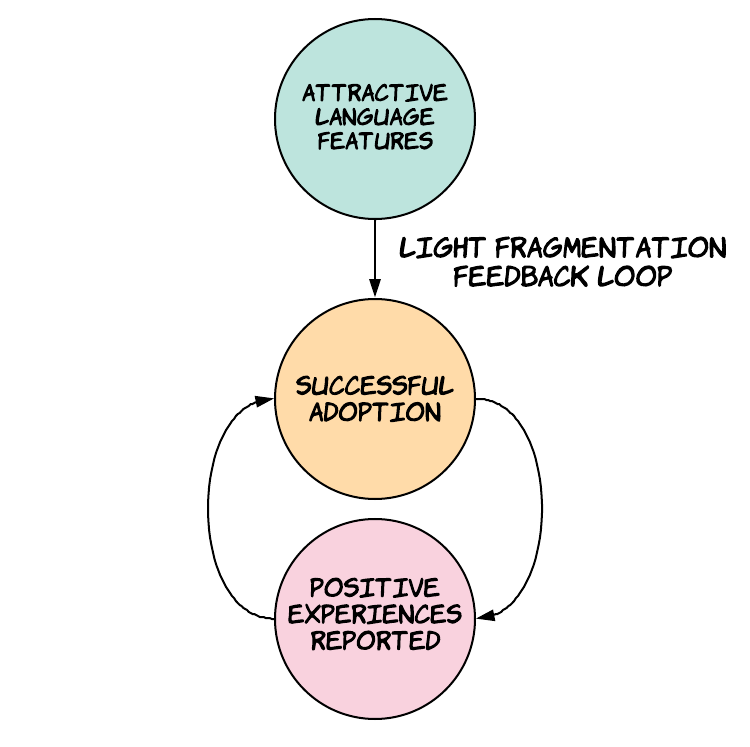

(False) Hope

The above two explanations are on the light side of the spectrum. On the light side, a new language comes along that is genuinely better than its predecessors, either in general or in a specific domain, and you make the informed decision to adopt that language. Then you sing its praises and encourage others to adopt it as well. Let’s call this the Light Fragmentation Feedback Loop.

Let’s now delve into the dark side of the spectrum. As r/ProgrammingLanguages shows us, a language can contain improvements upon existing languages, but that does not mean anybody is going to use it. To gain wide adoption, you need the language to be used in production by businesses who want to make money. And that means you need to convince CTOs, tech leads, and heads of engineering that some language, framework, or technology is going to improve the bottom line, whether by increasing the efficiency of the team or increasing the quality of the product.

One example that comes to mind is not a language but an architectural pattern: microservices. The industry watched as companies like Uber enjoyed success with the microservices pattern, and intelligent people in various startups went overboard trying to mimic that success in the wrong contexts, finding themselves with all of the drawbacks and none of the benefits.

Document-based storage has had a similar trajectory. In general, the grass is always greener on the other side. When you are intimately familiar with your current solution and its myraid issues, it’s too easy to be lured into thinking some shiny new technology will rescue you from all your problems. If only it were so simple! Then we wouldn’t have to blame ourselves when we write bad code, we could just blame the technology instead.

Selection Bias And Signalling

False hope largely depends on an asymmetry of information. Some of this asymmetry makes sense: there’s simply less information available about a new language than there is about old languages. But for the information that is available for the new language, there is also an asymmetry in the valence of that information, which is to say, there’s no shortage of praise for new languages, but it’s hard to find people balancing the praise with criticism. You’ll have one or two: ‘The Good The Bad, And The Ugly’ Medium posts, but other than that you have to do some digging to get a feel for where the warts lie.

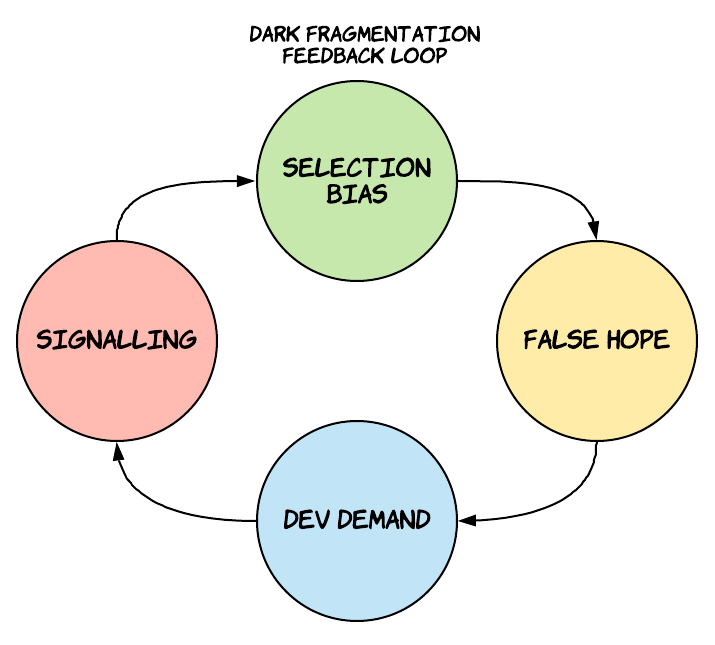

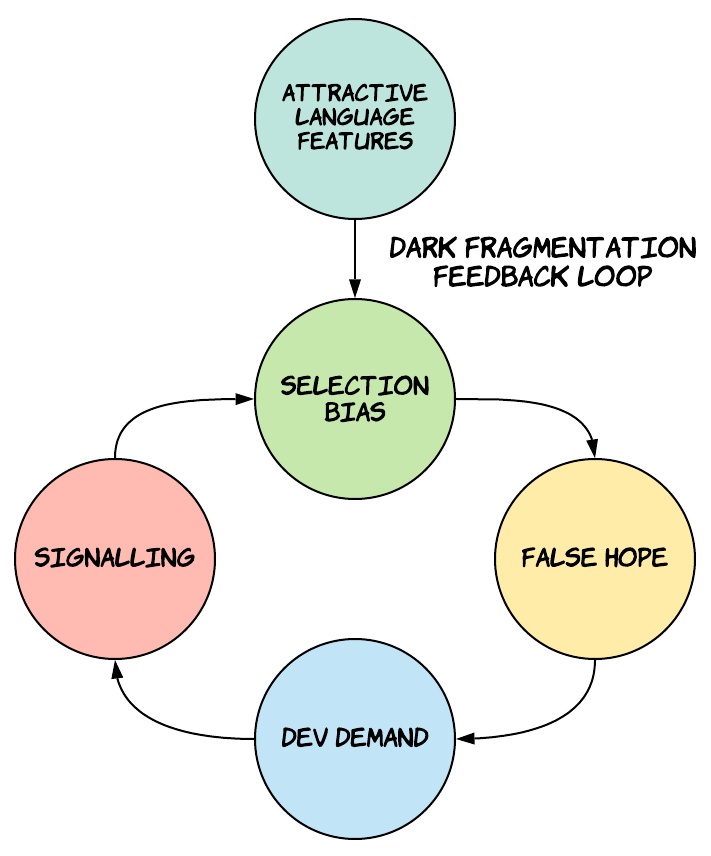

What accounts for this? Maybe it just takes time for the cracks to show in a new language. Or maybe there’s something more cynical (and therefore interesting) going on: I call it the Dark Fragmentation Feedback Loop

Our entry point to the feedback loop is that a language comes out that actually has some value. Then selection bias emerges. Early adopters of a language adopt it precisely because its sales pitch resonates. Rust’s sales pitch is that you can write performant code with an expressive type system and memory safety, so everybody who values those features comes along, sees that the language fulfills its promise, and says ‘Rust is great!’. Go’s sales pitch is that you can write concurrent code with a syntax so simple that any developer can learn it in a couple of hours. People come along, see that it fulfills its promise, and say ‘Go is great!’. The ideologies of the two languages are so diametrically opposed that the only reason you would learn both is if you have a genuine interest in learning any language, or if you are such a pragmatist that both sales pitches resonate with you in the context of different domains. Few people are like this, meaning most of what you’ll see is praise for the new language, whichever it is.

So we have disproportionate praise for a new language online thanks to selection bias. Companies then see that praise and think the language will solve all their problems (False Hope). Then we get companies hiring devs who know the language, paying extra for them. Why pay extra? The first reason is supply and demand: there aren’t going to be many devs around who know the new language so you need to pay more to get one. The second reason is that the kind of developer who has gone and learnt the new language since it came out is probably switched on, passionate, and curious: all traits worth paying extra for. The very fact that you know the language is a signal to the company that you have those traits. If you’re hiring for a Java or C developer, the fact they have experience in the language doesn’t tell you much about the person themselves, given they’ve had ample time to get that experience.

So the devs hear about these lucrative salaries on offer and start writing blog posts about the new language and starting side projects in it and participating in the languages’s community: in effect boosting the signal. Once you’ve signed on, why would you want to then criticise the language or the community? That would be biting the hand that feeds you. And so the incentive to signal enthusiasm and competency in the language closes the loop with more selection bias, leading to a further skewed information landscape.

Of course, it never lasts. Companies start to report their issues using the language in production. It becomes fashionable to announce that you’re ‘sunsetting’ the language. Regular devs start learning the language not out of curiosity but because it’s now part of their stack and therefore part of their job description, meaning experience in the language no longer signals the intelligence and enthusiasm it once did.

And then another new language comes along to restart the cycle again.

How Dark?

The above section summarises the dark feedback loop as uncharitably as possible for the sake of simplicity, but the reality is murkier. Maybe the light loop of just using a language because it solves your problem accounts for 99% of language adoption, and the dark loop accounts for 1%. But I can say with confidence that the Dark process is more than zero percent. How do I know that? Because I’ve participated in it myself! I saw Go rise in popularity, made some side projects in it, and blogged about it. On paper, I was making those side projects to better understand the language, because my company had already decided we were going to start using Go in upcoming work. I also genuinely enjoy blogging and find it helps me better understand concepts. I don’t intend to kill those side projects or stop that blogging. But I would be lying if I said I wasn’t aware of the signal being sent. I’ve become disillusioned with Go after spending so much time in it, but there’s no shortage of companies hiring for Go talent.

This is not to say I’m disavowing Go, I’ve had just as much trouble working in Rust. I’m just a grumpy bastard with unreasonable expectations of my languages. Even now as I type this I’m aware that public cricitism of a language might hurt my prospects down the line. But it would be hypocritical to omit in a post explaining how the dark feedback loop functions.

Who cares?

Does it actually matter if the dark feedback loop is a real thing? Companies get to hire talent, devs are incentivised to get outside their comfort zone and learn something new, and progress is made! That doesn’t sound so dark at all.

I don’t think fragmentation is actually bad on the whole: it’s the engine through which we experiment with new ideas and make progress as a field. Like the balkanisation of Western Europe, devs can jump ship from one language to the next, incentivising language designers to compete and respond to the needs of their users. We’ve seen functional language features gradually introduced in traditionally object-oriented languages, to much fanfare. If we were all content with our existing tech we’d still be writing assembly.

But the downsides must be recognised: much time has been wasted by companies adding a tool to their toolbox that they didn’t need, based on hype. Even in the absence of hype and the dark feedback loop, if a language solves a particular problem 50% better than the language you’re currently using, that doesn’t mean it’s worth the cognitive overhead of introducing that language to your stack. Like in my primary school choir, correctness does not necessarily trump consistency.

Will it ever end?

Despite the incentives created by the dark feedback loop, I predict that things will settle down eventually. Many languages are converging on what’s considered good practice, for example, removing implicit nullability, the so-called Billion Dollar Mistake. Graydon Hoare, author of Rust, disagrees, saying we have a long way to go. There are some interesting languages still maturing, like Gleam for example, but on the whole, I don’t think we’re going to see another heavy hitter like Rust coming along in quite some time. But if it does, you’ll probably catch me blogging about it!

Addendum:

My friend recently told me about how his company rewrote a ruby class as a Go service for performance, given that Go has better concurrency support. Bugs started cropping up everywhere, and the efficiency gains were marginal. ‘Let me guess’ I started, ‘to fix those bugs you just added a bunch of mutexes all over the place?’. Yep. In the end the company ported the code back to ruby, and found a way to substantially improve the performance just by identifying the initial problem and fixing it. A devout Gopher may argue:

Have you not listened to anything Rob Pike says about concurrency? You’re supposed to share state by communicating, not communicate with shared state! of course you failed with the Go approach, you were doing it wrong!

Fair point, fellow Gopher. If they did their research, maybe Go wouldn’t have been so bad. But if they really did their research in the first place, they wouldn’t have needed to reach for a new language! In general, we should work very hard to avoid adding unnecessary complexity to our tech stack, and adding a new language is the easiest way to add complexity.

Shameless plug: I recently quit my job to co-found Subble, a web app that helps you manage your company's SaaS subscriptions. Your company is almost certainly wasting time and money on unused subscriptions and Subble can fix that. Check it out at subble.com