Everything I Wish I Knew About Javascript Scoping A Week Ago

The second half of this blog post now lives in video form here

About a week ago I began a deep dive into the internals of Javascript (and similarly ECMAScript). Javascript is pretty whacky, and some people are more comfortable with that whackiness than others, so it took me a while to find explanations that properly satisfied my curiosity. Dmitry Shoshnikov’s wonderful blog post series on ECMAScript connected a lot of dots for me, but I wanted to create one big post that combines everything I’ve learnt.

What I want to do with this post is to only make claims that I can back up with direct experimental evidence, so I’ve included plenty of code snippets that you can run yourself. Alright, let’s go!

Variable Scoping

Your typical variable has three stages in its life:

- declaration

- initialisation

- usage

When you declare a variable foo you’re registering the fact that there is a variable called foo which other places can access. When you initialize foo, you bind it to an actual value. And then the variable can be used by other parts of the code. Here’s the typical example:

let x; // declare

x = 1; // initialize

console.log(x); // use

Why separate declaration from initialisation? One reason is to enable recursion. The factorial function, which takes a number like 3 and returns 6 (3 x 2 x 1) can be defined recursively (it calls itself internally). Consider this example in Go where we try to declare and initialize our function at the same time:

factorial := func(n int) int { // declare and initialize `factorial` at the same time

if n == 1 {

return 1

}

return n * factorial(n-1) // Error: undeclared name: factorial

}

Because we evaluate expressions before assigning them to variables, the compiler attempts to evaluate our function and comes across the factorial variable name and has no idea what it’s talking about because it hasn’t yet been declared. We need to declare our variable first so that the compiler knows what we’re talking about when it comes across the call to factorial inside the function.

var factorial func(int) int // declare `factorial`

factorial = func(n int) int { // initialize `factorial`

if n == 1 {

return 1

}

return n * factorial(n-1)

}

fmt.Println(factorial(3)) // 6 (i.e. 3 * 2 * 1)

Hoisting

Hoisting is a feature of various programming languages where declarations are done ahead of time so that you don’t need to worry about doing it yourself. When we say a function has been ‘hoisted’ we mean its declaration has been pulled up to the top of its scope before any code is executed in that scope. Go has hoisting for top-level functions but not for functions assigned to variables. Javascript has hoisting for all functions:

const factorial = n => {

if (n === 1) {

return 1;

}

return n * factorial(n - 1); // no error

};

console.log(factorial(3)); // 6 (i.e. 3 * 2 * 1)

It’s worth mentioning that there are different ways of defining functions, and they are hoisted differently. Function declarations are hoisted differently to variables bound to function expressions:

function outer() {

debugger; // foo: undefined, bar: f bar(n)

const foo = function(n) {

// function expression assigned to a variable

return n + 1;

};

function bar(n) {

// function declaration

return n + 2;

}

bar();

foo();

debugger; // foo: f(n), bar: f bar(n)

}

outer();

I’m wrapping many of these examples in an outer function because behaviour differs at the top level (i.e. the global scope). I’ll explain later!

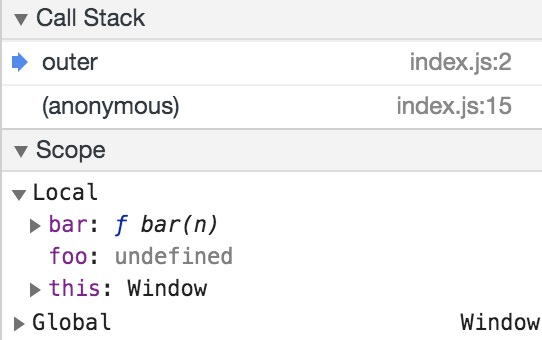

If you open up your browser dev tools (cmd+shift+i in Chrome), you’ll see our local scope at the first debugger breakpoint:

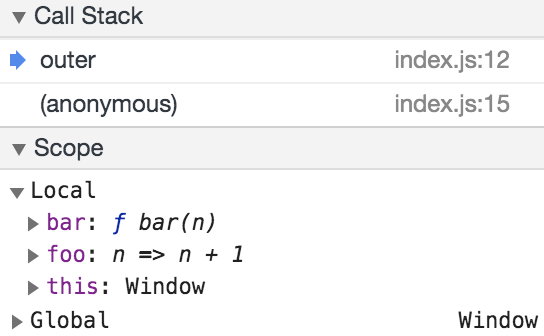

And here it is at the second breakpoint:

Though the term ‘hoist’ typically refers to declarations, we see here that bar (a function declaration) has both its declaration and its initialisation hoisted to the top of outer’s scope, whereas foo (a variable bound to a function expression) only gets its declaration hoisted, meaning it is undefined until it’s explicitly initialised.

This might seem strange, but it turns out that in Javascript, all variables (as opposed to function declarations) have their declarations (and not their initialisations) pulled up, whether or not the variables are themselves bound to a function. To demonstrate:

function outer() {

debugger; // a: undefined, b: undefined, c: undefined

var a = 1;

let b = 2;

const c = 3;

debugger; // a: 1, b: 2, c: 3

}

outer();

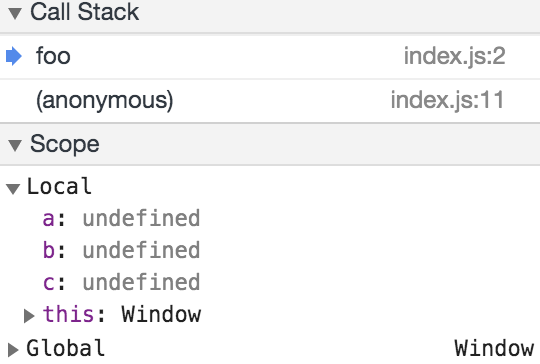

At the first breakpoint:

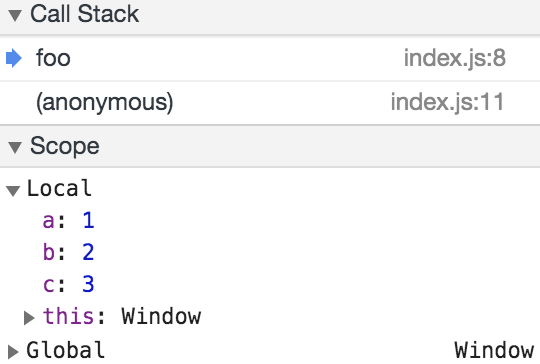

At the second breakpoint

In this case, we have a, b, and c all being declared at the start of the function call, with a value of undefined. It’s only later that they are given their ‘initial’ values.

Hoisting variables

Hoisting functions makes sense, as we’ve seen with the example of our recursive factorial function. But hoisting variables? Why would anybody need that?

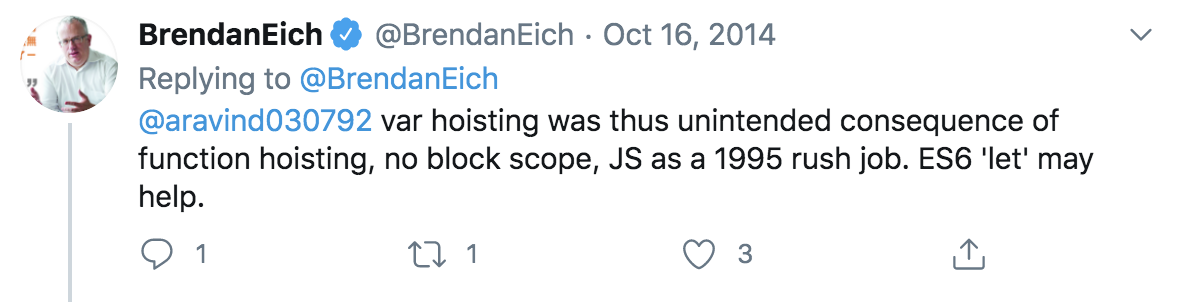

Brendan Eich, creator of Javascript, says:

let may help with what?

let was introduced in ES6 to solve some of the problems of var. For example, even though variables declared with either let or var are hoisted, var won’t raise if you try to access an uninitialised variable:

function outer() {

console.log(x); // undefined

var x = 5;

console.log(x); // 5

}

outer();

Compare this to let:

function outer() {

console.log(x); // Cannot access 'x' before initialization

let x = 5;

console.log(x); // isn't reached

}

outer();

Another benefit of let is that it’s scoped to the block rather than the function. For example:

function outer() {

for (var i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

console.log(i); // 0, 1, 2, 3, 4

}

console.log('after loop: ', i); // 5

}

outer();

Here our i variable is declared with var and so it is scoped to the function. This means it’s accessible from anywhere in the function. What about if we swap out var for let:

function outer() {

for (let i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

console.log(i); // 0, 1, 2, 3, 4

}

console.log('after loop: ', i); // Uncaught ReferenceError: i is not defined

}

outer();

Now i is only scoped to the for loop’s block, meaning once we leave the block, the variable can’t be accessed (and in this case its memory is freed up for some other variable to use)

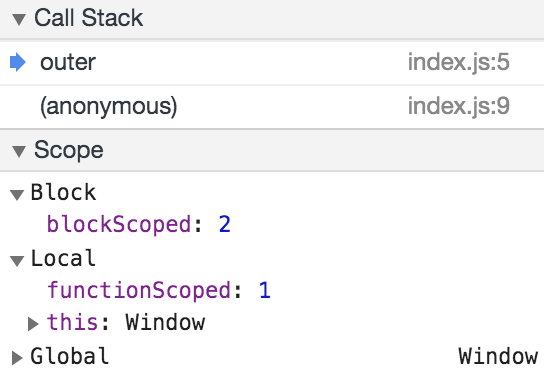

You can also see that var and let are placed on two different scope objects in the debugger despite both lexically appearing in the same block scope:

function outer() {

if (true) {

var functionScoped = 1;

let blockScoped = 2;

debugger;

}

}

outer();

Execution Contexts

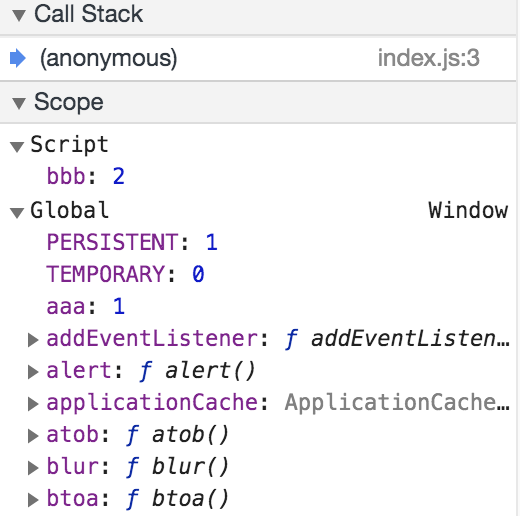

We’ve been wrapping all of these examples in outer functions. What happens when we’re not in a function and instead we’re sitting at the top level of a program?

var aaa = 1;

let bbb = 2;

debugger;

bbb is scoped to the script (which literally means the script tag in your html) and aaa is scoped to the global object (which will be window if you’re in a browser).

How is it even possible that our aaa variable ends up as a property of the global object? To explain this we need to introduce some new concepts. It’s about to get intense but I’ll be with you the whole way. Let’s take a look at this example:

var a = 1;

let b = 2;

function outer() {

let c = 3;

var d = 4;

function inner() {

let b = 5;

let c = 6;

// diagram refers to this point in the code (i.e. outer has been called, which has in turn called inner)

console.log(a); // 1

console.log(b); // 5

console.log(c); // 6

console.log(d); // 4

}

inner();

}

outer();

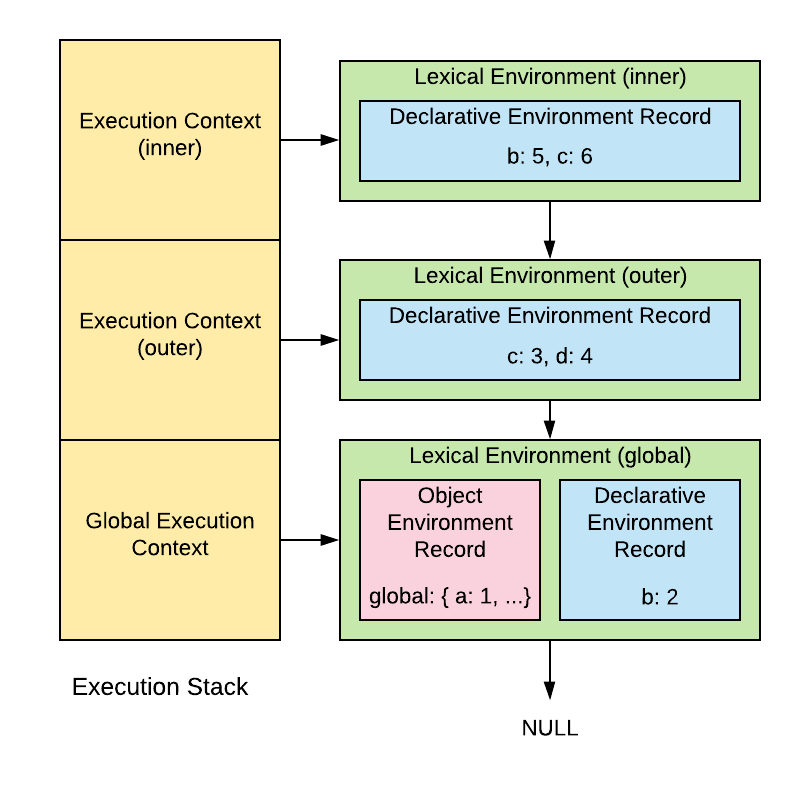

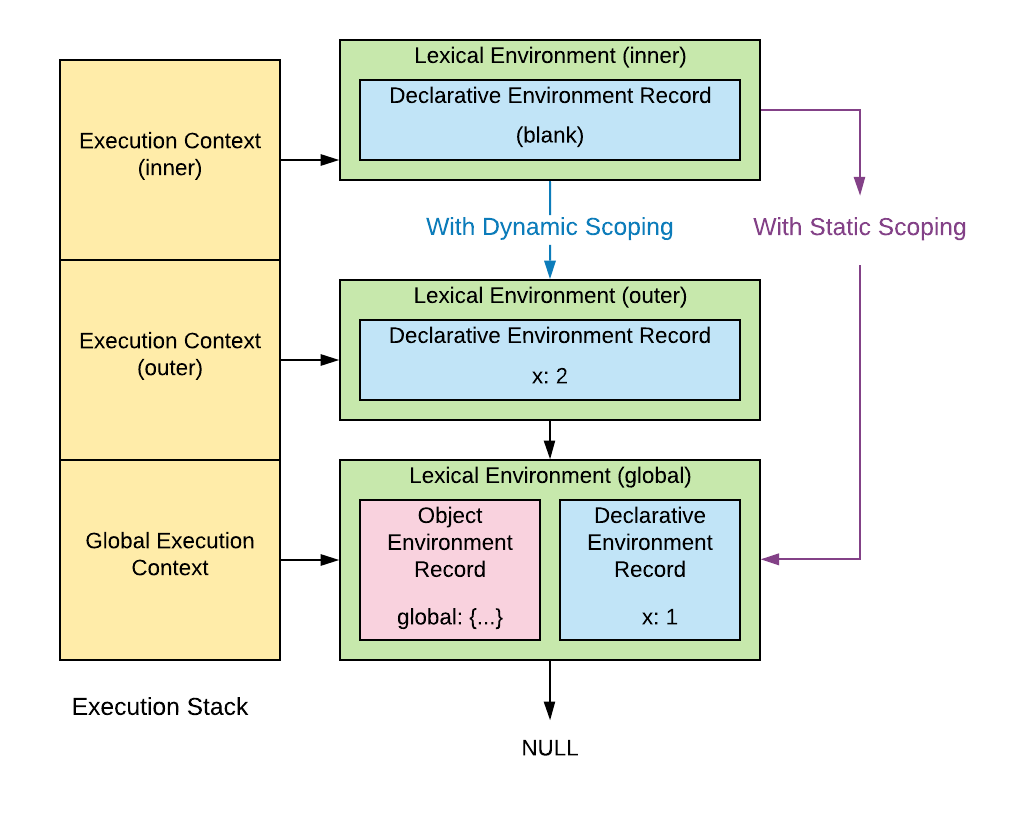

Alright so what’s happening in this diagram? On the right we’ve got a stack of execution contexts. What are they? An execution context is analogous to a stack frame on a call stack. When we call and enter a function a new execution context is created on the call stack to keep track of our state as we execute the function’s code.

If we’re in inner and we want to log the value of the variable a, we first look at our execution context’s lexical environment (shown in green). This contains an environment record for internally storing the locally defined variables. In this case it’s a declarative environment record, which just means it stores the variables in an efficient way hidden from the programmer. We can’t find our ‘a’ variable there so we follow the lexical environment’s reference to its parent lexical environment, whose environment record also doesn’t have an a variable. Next up we arrive at the global execution context’s lexical environment, which contains a composite environment record consisting of both a declarative environment record, and the other kind of environment record, the object environment record.

Back in the day, every lexical environment used an object environment record which stored all local variables as properties on a ‘binding object’ which was just a Plain Old Javascript Object (POJO). Using a POJO to store local variables of a function turns out to be inefficient and also breaks encapsulation, which is to say your local variables could be messed with by Javascript code that could access the binding object. Nowadays everybody agrees storing local variables on an object is a bad idea, but an exception is made for var variables defined in the global execution context (i.e. at the top level of the program) for legacy reasons. That’s why b, which is declared with let ends up in the global execution context’s declarative environment variable, rather than being stored as a property on the global object like a. Variables stored in the declarative environment record of the global execution context will appear under the ‘Script’ section of your debugger, but don’t be mislead by the name: all scripts share the same global execution context, meaning all scripts share whatever ends up in that Script section.

The main takeaway here is to use let, not var. Even better, use const. const is the same as let but disallows reassigning of variables.

Static vs Dynamic Scoping

Okay now that we’ve talked about how local variables are scoped let’s talk about non-local variables. What will this script output?

const x = 1;

const inner = () => {

console.log(x);

};

const outer = () => {

const x = 2;

inner();

};

outer();

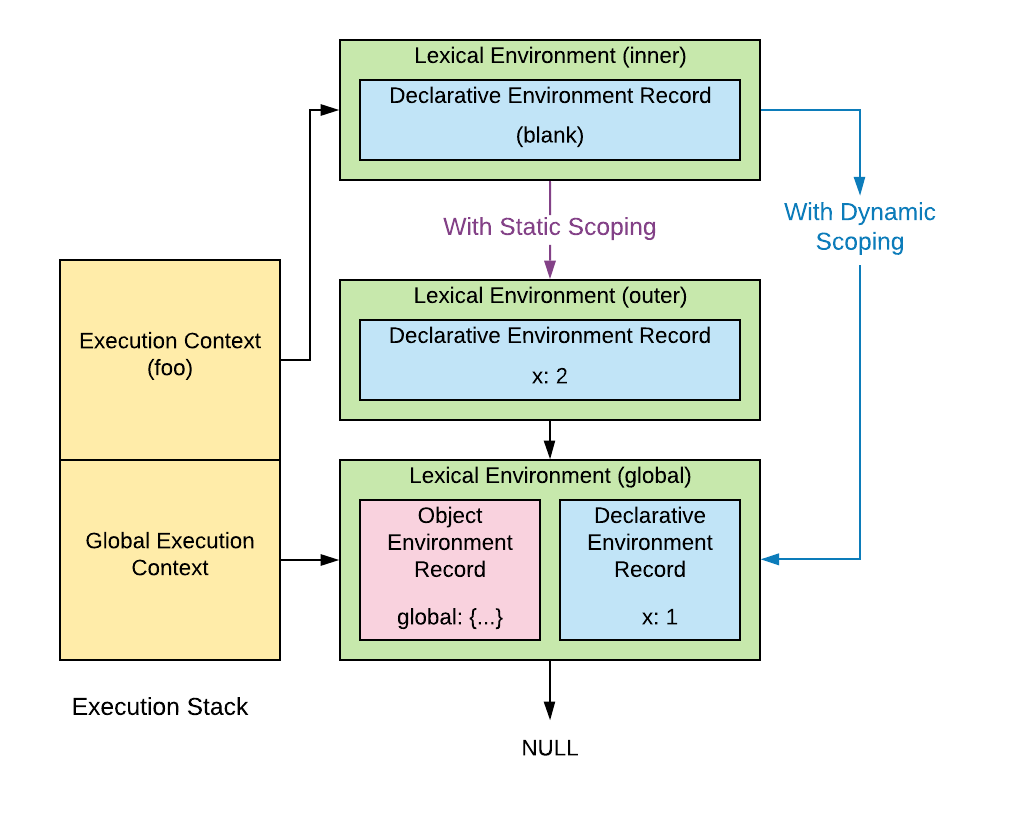

The answer is 1. Why? When inner is called, x is defined in outer’s execution context (stack frame) which sits just below inner’s execution context, but Javascript doesn’t care about that. Javascript uses static scoping, meaning it only cares about which variables are in-scope at the time a function is created. When inner is created, the top level x (value 1) is in scope and outer’s x (value 2) is not, so it only refers to that x (value 1) when it’s called.

So, in order to determine the value of a variable, static scoping employs a scope chain based on what was in scope at the time of a function’s creation, rather than at the time a function is called. So the first item in our chain is the lexical environment of inner, and its parent is the global lexical environment. We completely skip the lexical environment of outer because it doesn’t actually lexically contain inner on the page. Static scoping is also called lexical scoping because just by looking at the lexemes i.e. letters in a file you can tell what variables are in scope. This also explains how ‘lexical environment’ got its name: it stores the variables you can see just by looking at the page without worrying about where a function was called from.

Why is this important? Doesn’t every language do the same thing? Nope! In fact you’ve used one that doesn’t. It’s called bash.

x=1

function inner {

echo $x

}

function outer {

local x=2

inner

}

outer

Unlike our analogous javascript program above, this bash script will echo 2 because bash uses dynamic scoping, not static scoping. With dynamic scoping, if a variable is referenced that is not defined locally, we go down the callstack looking for the first occurence of it and then use that. In this case, the scope chain consists first of the inner function’s environment which does not contain an x variable and then we go back to the outer function’s environment which does with a value of 2 so we stop there.

Bash doesn’t have a concept of a lexical environment or an environment record, but if it did, it would follow the path for dynamic scoping like so:

Dynamic scoping leads to all kinds of crazy edge cases, where you can accidentally mutate variables defined several functions up the call stack. It also makes it hard to reason about what’s in scope just by looking at the page lexically, because you can’t know which outer functions are going to call the inner function, and what permutations of stack frames there could be.

Static scoping is not without its own problems though: perhaps not for the developer but for the compiler. At the time of a function’s creation, static scoping cares about which variables are declared and in scope. But when that same function is called, we still want to know the values of those variables, which might have changed since the function was declared. This begs the question: how does javascript keep track of variables which are no longer in scope and therefore cannot live on the call stack?

Closures

Let’s consider a slightly modified version of the last program:

const x = 1;

const outer = () => {

const x = 2;

const inner = () => {

debugger;

console.log(x); // 2

};

return inner;

};

const foo = outer();

debugger;

foo();

Here, the inner function is defined inside the outer function. The first thing to note is that now we’ll be console logging x with a value of 2, not 1, because the x from the outer function appears first lexically as we zoom out from the inner function. But the more important thing is that by the time we call outer and we’ve assigned our inner function to foo, outer’s execution context (stack frame) can no longer live on the stack because we’re now outside that function completely. So how can foo know to output 2 when we reach console.log(x)?

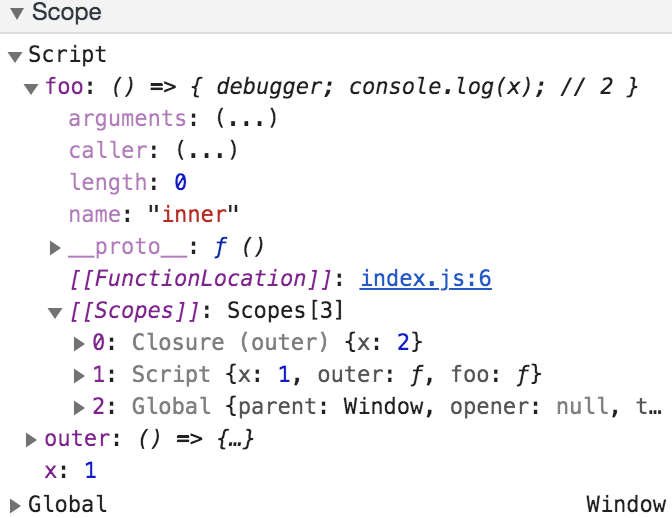

This brings us to closures. A closure is simply a function paired with a reference to its parent environment. When a function makes reference to an outer function’s variables, it’s said to capture those variables, or ‘close over’ those variables (hence the term ‘closure’). In this case when we create our inner function we actually create a closure consisting of the inner function and a reference to the lexical environment of the outer function. In the debugger we can get a rough idea of how this is stored:

When inner is created, it stores an internal [[Scopes]] property which captures the lexical environment of the outer function. Then, when we call foo we use the [[Scopes]] property to traverse the scope chain and find the value of x.

Dynamic scoping provides no way of closing over variables, because it will always traverse the call stack itself to find the value of a given variable at runtime. That means as soon as an outer function returns, its local variables are lost. Static scoping allows for closures, but by supporting closures we introduce some new complexities to memory management.

ECMAScript vs The Real World

So far I’ve been treating the ECMAScript spec as if it was directly implemented in the real world, but in some debugger screenshots you might have noticed a couple places that don’t seem one-to-one with the spec. The way ECMAScript talks about closures differs quite a bit to how they are implemented in practice. In ECMAScript, every function actually constitutes a closure because each function contains a reference to its lexical environment in an internal property called [[Environment]]. So every function has access to its own scope via its lexical environemnt, and by following the references you can go all the way up to the global lexical environment.

For this setup to be honoured in the real world, we would need to store basically everything on the heap rather than the call stack, because any inner function that closed over an outer function would need to keep a reference to all its outer function’s variables, even if it only closed over one of them. In fact, according to the ECMAScript, even inner functions that don’t explicitly capture any variables from the outer function will still capture those variables via the reference to the parent’s lexical environment.

Admittedly, most things in Javascript are stored on the heap anyway, but real-world implementations of Javascript will try to spare themselves unnecessary heap allocations whenever possible.**

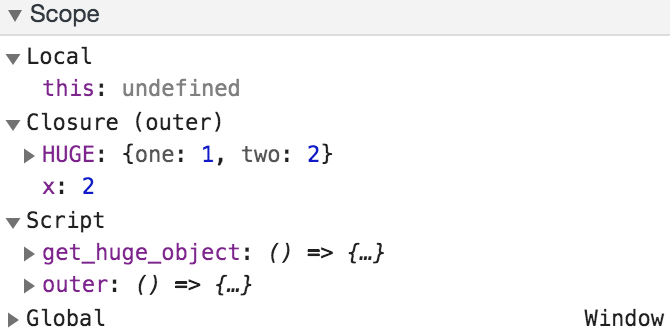

Let’s look at how V8, Chrome’s javascript implementation, handles closures. In V8, a ‘Context’ is created inside a scope if there are any functions defined in that scope that reference any of the scope’s variables. The Context contains all the variables in that scope which were captured by one or more functions. That context then lives on the heap rather than the stack and the functions which captured any variables retain a reference to the context. This has a couple of interesting implications:

- primitive variables that otherwise would have lived on the stack (or a register) now live in the heap

We don’t want to have multiple copies of our variables made, given that they could easily get out of sync leading to bugs. That means if we have a variable of type ‘number’ which otherwise would have lived on the stack or a register, if it’s captured by an inner function it will now live on the heap.

- large objects may now stick around in the heap longer than before

Consider the following code:

const outer = () => {

const x = 2;

const y = 1;

const HUGE = { one: 1, two: 2 }; // imagine this is actually a huge object

const bar = () => {

console.log(HUGE);

};

const inner = () => {

debugger;

console.log(x);

};

return inner;

};

const foo = outer();

// do lots of time-consuming stuff

foo();

When our debugger hits the breakpoint in our inner function, we see in the ‘scope’ section that there is a ‘Closure’ (i.e. a V8 Context) that contains x and HUGE. y is not captured by either of bar or inner so it stays on the stack. x is captured by inner and HUGE is captured by bar, so both of those get added to the Context. The interesting thing is that despite bar being short-lived (and indeed not even being called), the fact that inner still references the Context means that our HUGE object hangs around until our foo variable is no longer in scope. Vyacheslav Egorov goes into more detail in his blog post here, but it’s interesting to think about how the ECMAScript can differ from its implementation.

this

Earlier I said that javascript uses static scoping, not dynamic scoping like bash. Though this is true for the most part, there is one important exception*: the this variable. To demonstrate:

var x = 1;

const obj = {

x: 2,

a: function() {

console.log(this.x);

},

};

const bar = obj.a;

bar(); // 1

obj.a(); // 2

this is not really a variable: once we enter a function’s scope, its value does not vary. But it is a ‘binding’ in the sense that in a function a value is bound to it. If to the left of the () we have an object property access (e.g. foo.a) we’ll set this to the object (foo) upon entering the function. If not, we’ll pass in the global object as this. There is some extra nuance to it that is well explained here but that’s the gist.

One might wonder: why violate static scoping for the sake of this one special binding called this? The reason is that because functions are first class, they can be assigned as properties on different objects. Consider the following:

const obj = { x: 1 };

const obj2 = { x: 2 };

function foo() {

console.log(this.x);

}

obj.bar = foo;

obj2.bar = foo;

obj.bar(); // 1

obj2.bar(); // 2

So functions can be defined in isolation from the objects that they act on, meaning behaviour can be shared between quite different objects. Sharing of behaviour is what inheritance is all about, and indeed, javascript’s prototypal inheritance makes use of this as well. If you attempt to call a function on an object and no such function is found, we travel up the prototype chain until we find a function with a matching name and call it. That function can access data or even other functions defined on the base object (or, failing that, the prototype chain can be traversed again) by invoking this for example this.x:

function A() {

this.x = 1;

this.blah = function() {

console.log('foo');

};

}

A.prototype.foo = function() {

console.log(this.x); // 1

};

obj = new A(); // { x: 1 }

obj.foo(); // foo function not defined on object, but is defined on the object's prototype

See here for an proper explanation of prototypes.

So the this binding constitutes a rare and strange exception to Javascript’s static scoping, but it enables shared behaviour and prototypal inheritance. If you want this to conform to static scoping you can use the arrow function syntax. Consider this program which does not use an arrow function:

function Foo() {

this.x = 1;

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(this.x); // undefined (attempts to find x property on the global object)

}, 1000);

}

var f = new Foo();

It logs undefined because when the callback to setTimeout is called, it’s called directly on the global execution context and so it’s passed the global object as this. Compare to using an arrow function:

function Foo() {

this.x = 1;

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(this.x); // 1

}, 1000);

}

var f = new Foo();

Internally, an arrow function simply assigns this to a variable and then closes over that variable in the callback. You can see this by looking at the babel transpilation of the above program:

'use strict';

function Foo() {

var _this = this;

this.x = 1;

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(_this.x); // 1

}, 1000);

}

var f = new Foo();

Conclusion

The scoping logic of javascript is truly confounding, but despite all the awkwardness of legacy design decisions from the 90s, there is elegance to be found in how the language tackles problems that all sufficiently sophisticated languages need to tackle in some way. Static scoping makes it easy to reason about code, especially when dealing with first class functions, but a hint of dynamic scoping, provided through the this binding, empowers the programmer to share behaviour between objects, unconstrained by the rigidity of a class-based inheritance taxonomy.

Hopefully this post has illuminated some of the design decisions behind common javascript features and given a name to some concepts that might have already been swimming around in your head. Thanks for reading!

Addendum #1 Investigating the Context object with heap snapshots

Chrome has a heap snapshot tool in its dev tools that we can use to see when context objects are created and what they contain. Consider the following program:

const outer = () => {

debugger;

const barStr = 'captured by bar';

const innerStr = 'captured by inner';

const uncapturedStr = 'not captured';

{

debugger;

const blockStr = 'block scoped str captured by bar';

const bar = () => {

console.log(barStr);

console.log(blockStr);

};

debugger;

}

const inner = () => {

console.log(innerStr);

};

return inner;

};

debugger;

outer()();

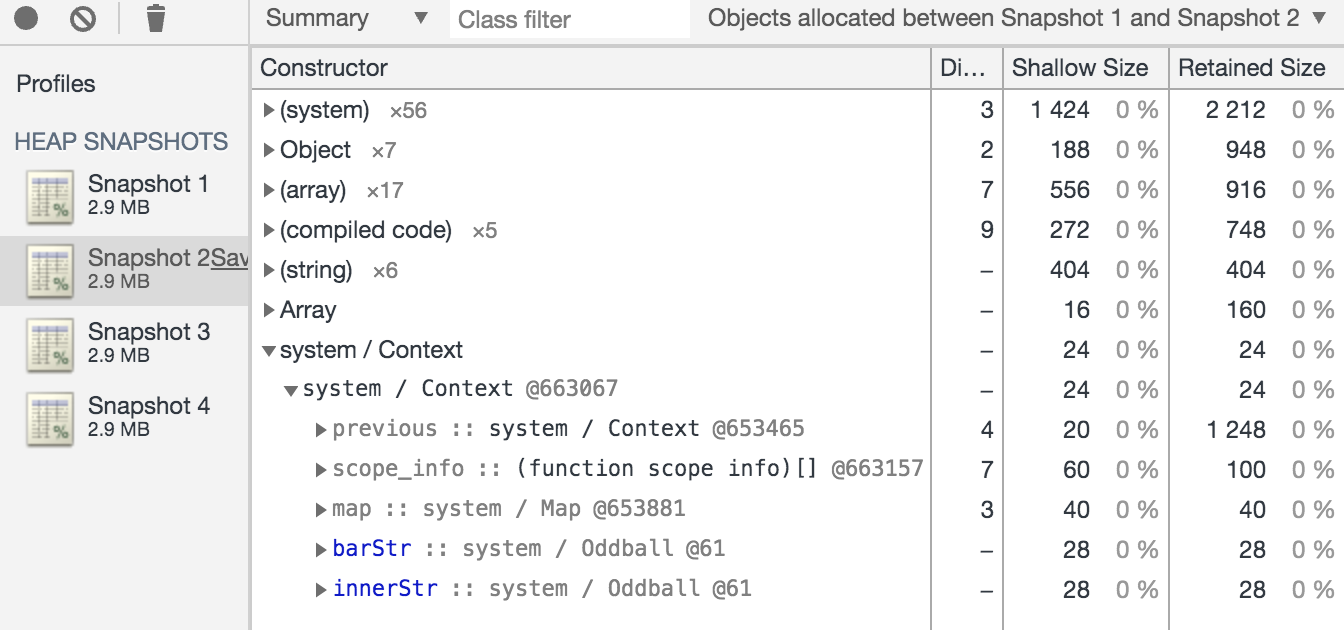

bar captures barStr from outer’s scope, as well as blockStr from a local block scope that we’ve created with curly braces (an uncommonly used feature but it’s allowed by the language). inner captures innerStr from outer’s scope. That means uncapturedStr is left uncaptured. We can create a heap snapshot at each breakpoint and compare adjacent snapshots to see which objects were created in the heap. If we compare the heap snapshot right before we enter outer and right after we enter, we see that it has already created the Context object and it contains barStr and innerStr (and notably does not contain uncapturedStr.

So clearly the contents of inner and bar have been inspected ahead of time to see which variables they capture from outer’s scope.

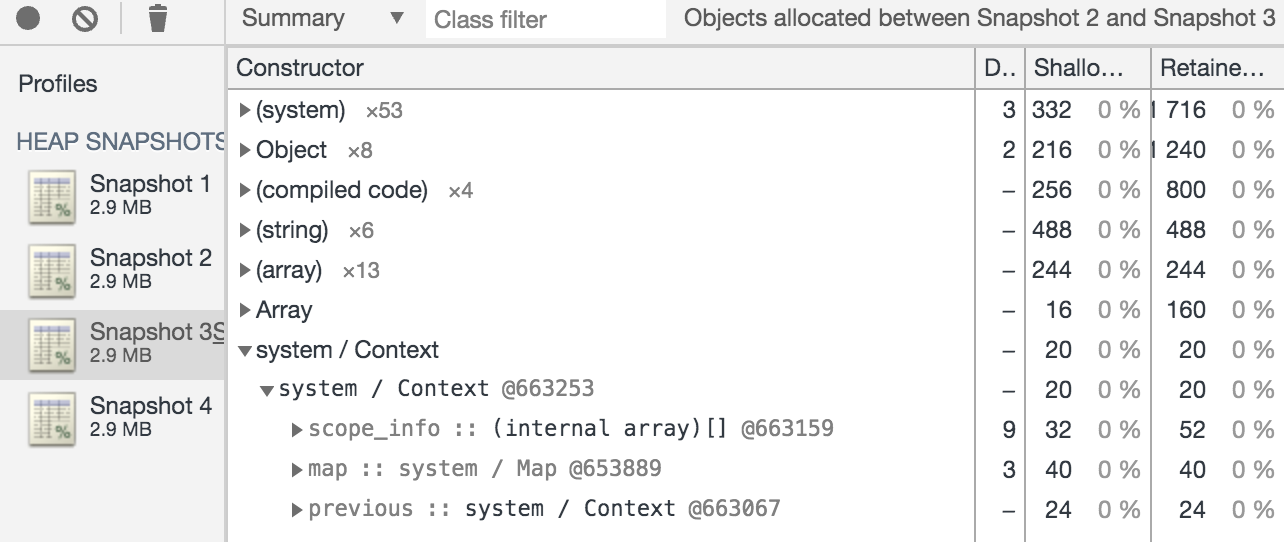

We can likewise see a context has been created upon entering the block that contains bar

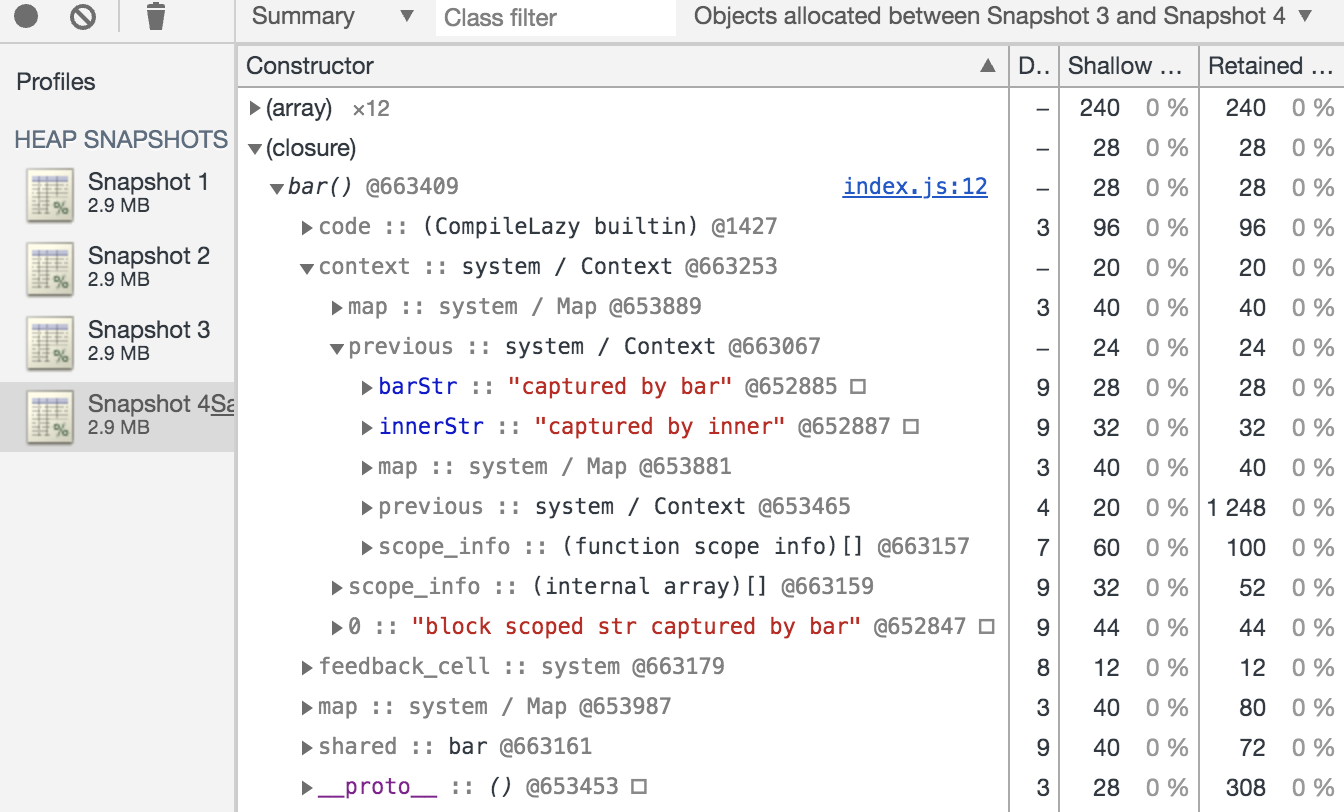

Notably here it’s not obvious that our blockStr is included in the context. I’m actually not sure what explains the difference here. If we look at which objects were created by the final snapshot:

So now we see that we’ve assigned the context from the previous snapshot (@663253) to this function, and it contains a reference to blockStr (though still notably no variable name shown for some reason) as well as a reference to the previous (i.e. parent) context (@663067) which itself contains barStr and innerStr. So looking at these snapshots we learn a few things:

- Context objects are created as we enter a function or block scope, containing only those variables which are captured

- Context objects contain a reference to their parent Context, which allows closures to traverse the Context chain to obtain the value of a captured variable.

Pretty cool!

** Addendum #2 Stack vs Heap

This section has been pulled out of the main post into an addendum because from the few places I’ve read online, closure optimisations are more about registers vs memory than stack vs heap, but I still think it’s worth talking about.

I want to give a brief explanation of why storing things on the stack is preferable to storing them on the heap. Both the stack and the heap live in RAM so accessing variables in either one is quite fast, however the stack is far better for memory management. Given the stack’s constraint of only allowing you to add or remove things from the top, deallocating memory is as simple as moving a stack pointer. When we enter a function and create an execution context for that function, we simply move the pointer up to make room on the stack, and then add the variables there. When we leave the function, we then move the pointer back down again to free up that memory.

The heap is comparatively far more challenging to manage. Because objects in the heap could be referenced from various places, we need to maintain an internal register of how many things are referencing an object, and only once an object is orphaned (i.e. no longer referenced by anything) do we go and free up the memory it was using. This is the job of the garbage collector. But garbage collection is not a simple as freeing up memory for orphaned objects. Because objects can be created anywhere in the heap in any order, as we free up memory we end up with a swiss cheese situation where you might have a gigabyte of available memory, but it’s fragmented into a bunch of tiny gaps where we’ve recently freed up memory from an orphaned object. So the garbage collector must also periodically shuffle objects around in memory so that when we need to store a large object we can actually fit it in the available space.

With that said, the only reason we introduce the call stack, and don’t just do everything on the heap, is because we can, not because of some fundamental computer science dictum. If we know that we can allocate memory in a first-in-last-out (FILO) fashion, then we can make use of a stack to avoid the annoyances of garbage collection.

Appendices:

* There are, in my opinion, unimportant exceptions like with which is disallowed in ES5 strict mode

References

Shameless plug (which appears on every blog post, not just this one, so don't think that I'm opportunistically posting this specific post just for the sake of doing this plug): I recently quit my job to co-found Subble, a web app that helps you manage your company's SaaS software licences. Your company is almost certainly wasting time and money on shadow IT and unused/overprovisioned licences and Subble can fix that. Check it out at subble.com