Docker: where to draw the line?

There are four approaches to using Docker in development:

- Don’t

- Put databases in docker

- Put databases and application server in docker

- Go all-in

Let’s consider the pro’s and con’s of each approach

1. Don’t

This is the OG approach. One major benefit of not using docker in development is that docker runs on linux and if you’re on windows or mac, you’ll need to run docker in a virtual machine which will use more resources than if you ran everything natively1. On the other hand, before docker, it was common to use bespoke virtual machines to run dev environments, and that really sucked.

The downside of running everything natively is that each developer’s machine can vary wildly, and when things go wrong, there’s a good chance that the problem is caused by some idiosyncracy of a developer’s host environment. Troubleshooting this can be a nightmare.

Some languages are better for this approach: if you can compile your code to a native binary, with all the important stuff baked in, then the need for docker is lessened compared to using a dynamic language like ruby or PHP.

One of the major advantages of this approach is that you don’t need to teach anybody how to use docker. Docker is not that complicated, but it’s complicated enough that people can easily get stuck troubleshooting it. And, plenty of people have depressingly inefficient workflows with it (observing this was one of the reasons I made Lazydocker).

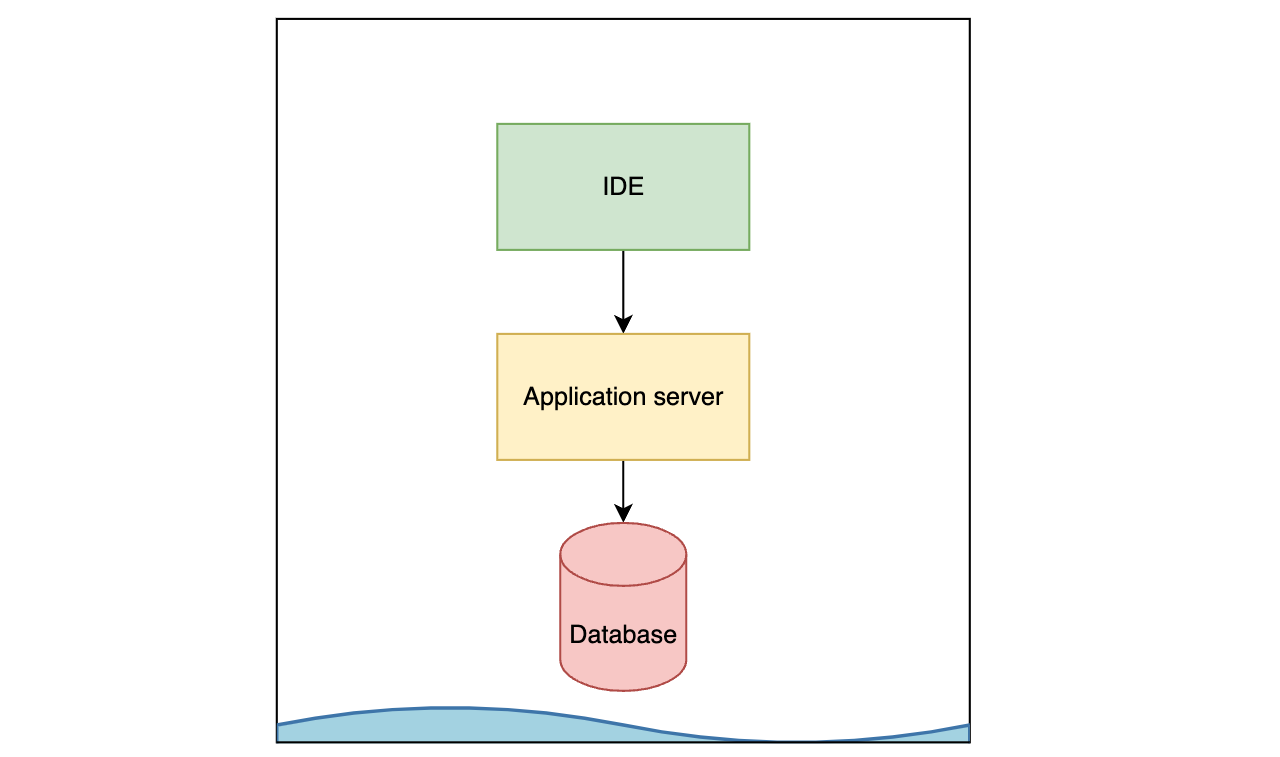

2. Put databases in docker

Okay so now we’re actually using docker. With this option, and the remaining options, the tradeoff to keep in mind is this:

- Everything below the line is standardised (that’s good)

- Any data that needs to cross the line becomes more finicky (that’s bad)

Putting only the databases (postgres, redis, etc) in docker is a common approach, and it has several benefits. Devs don’t need to set up databases natively, you can troubleshoot DB issues without worrying about the host machine’s idiosyncrasies, and importantly, the only data crossing the line is HTTP requests between the application server and the database(s) which is seamless.

The database doesn’t need a bind mount: it can just have its own volume, meaning that you don’t need to worry about filesystem IO crossing the line (which is typically slow).

The downside is that everything above the line remains subject to the idiosyncrasies of the host machine.

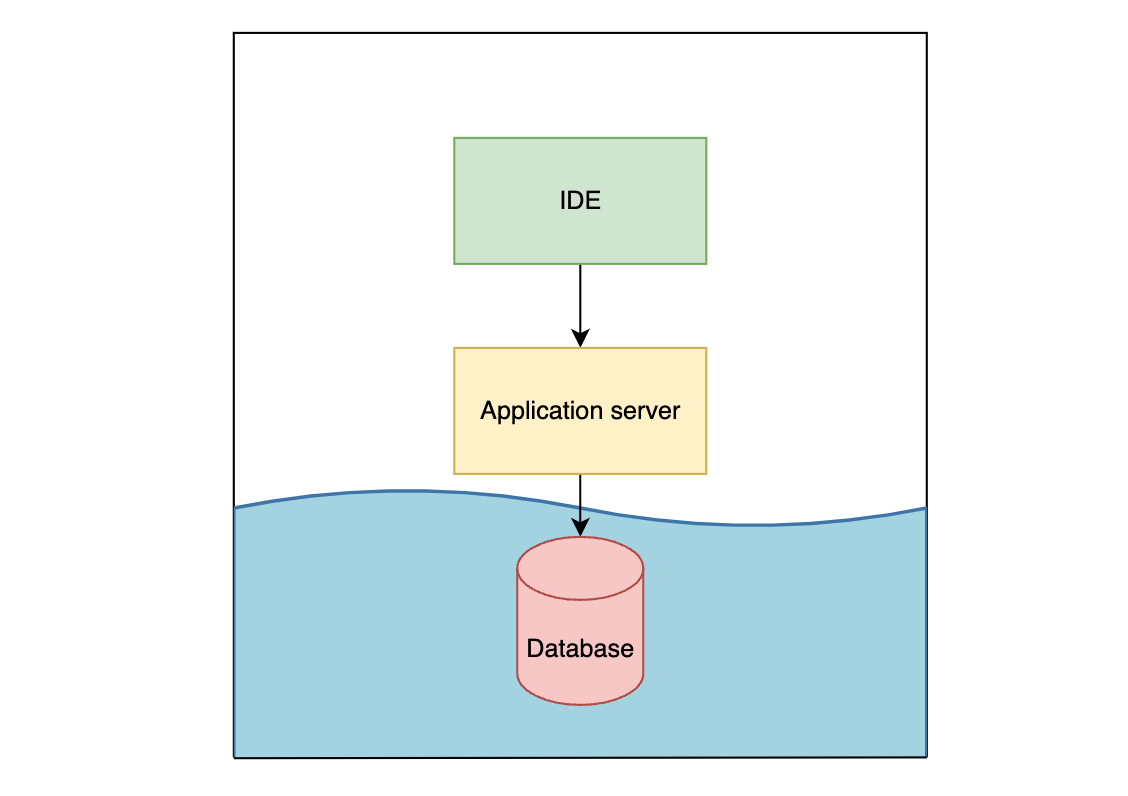

3. Put database and application server in docker

So, why not include the application server as well? This approach has big upsides and big downsides.

One big upside is that you can now include OS-level dependencies to the docker image itself, rather than require devs to add them to their host machines. This speeds up onboarding time and simplifies troubleshooting when things go wrong.

Another benefit is that, depending on how similar your production image is to your development image, your local environment more closely mimics production.

Okay, what about the downsides? Firstly, you’ll be bind-mounting your codebase which incurs an IO cost because your host machine and your docker virtual machine use different filesystem representations. You could get around this by just having all the code live inside docker but that itself is a headache (e.g. if you want to read through code without running docker).

Secondly, your application server’s library dependencies will need to live in docker (because often dependencies use native extensions) but your IDE also needs access to those dependencies for the sake of linting, type checking and the like. So you’ll end up having to maintain two separate sets of dependencies, one for your host and one for docker, and you’ll be running bundle install, npm install etc twice every time you need to add/update a dependency. Keeping these two sets of dependencies in sync is super annoying.

Another annoying thing is that to do anything in your application server’s shell, you’ll need to first run a docker command to open that shell i.e. docker compose run --rm api bash. In fact your scripts will likely end up being split into two groups: half to be run from the host (and so they include docker commands) and half to be run from within the container. This gets very confusing and messy.

Remember the rule: everything below the line is standardised, and the data which crosses the line becomes finicky. When you draw the line above the application server, you end up with quite a lot crossing that line: requests from your browser to the application server, bind-mounted files, shell commands, attaching your terminal to the server, etc. In each place, you’ll feel the pain from that extra bit of friction.

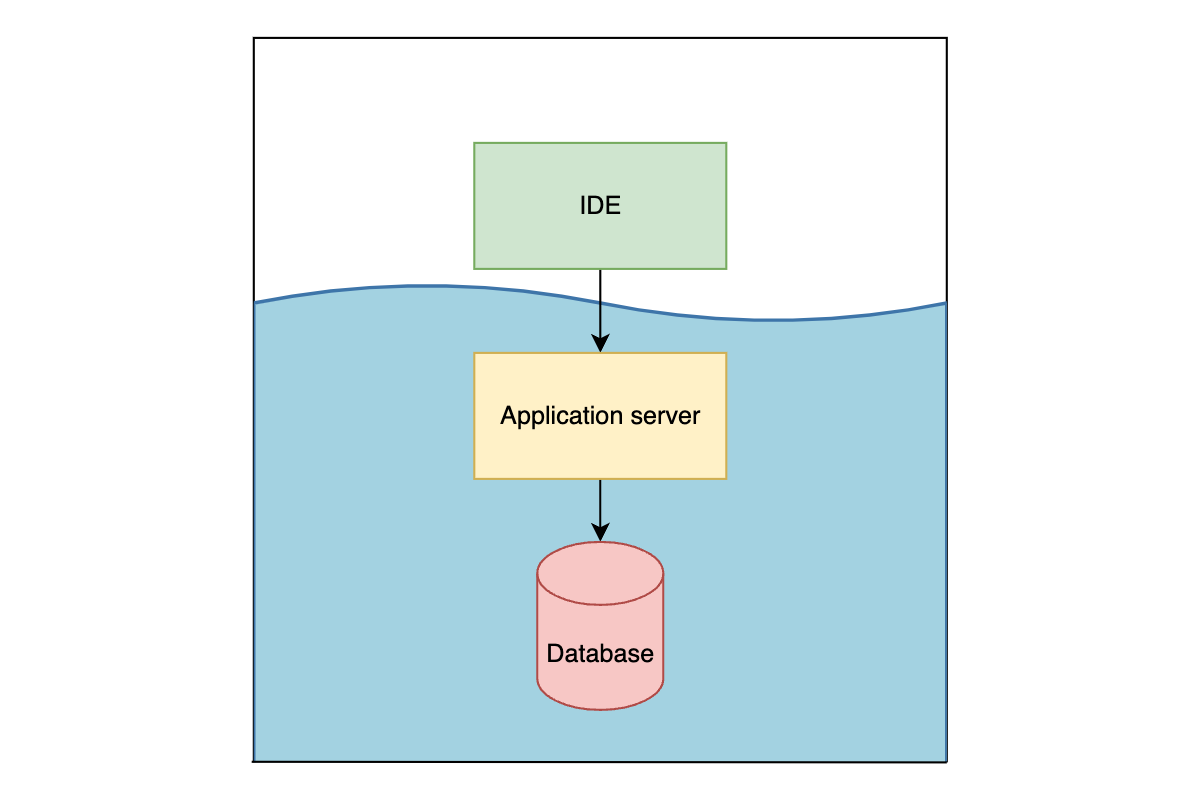

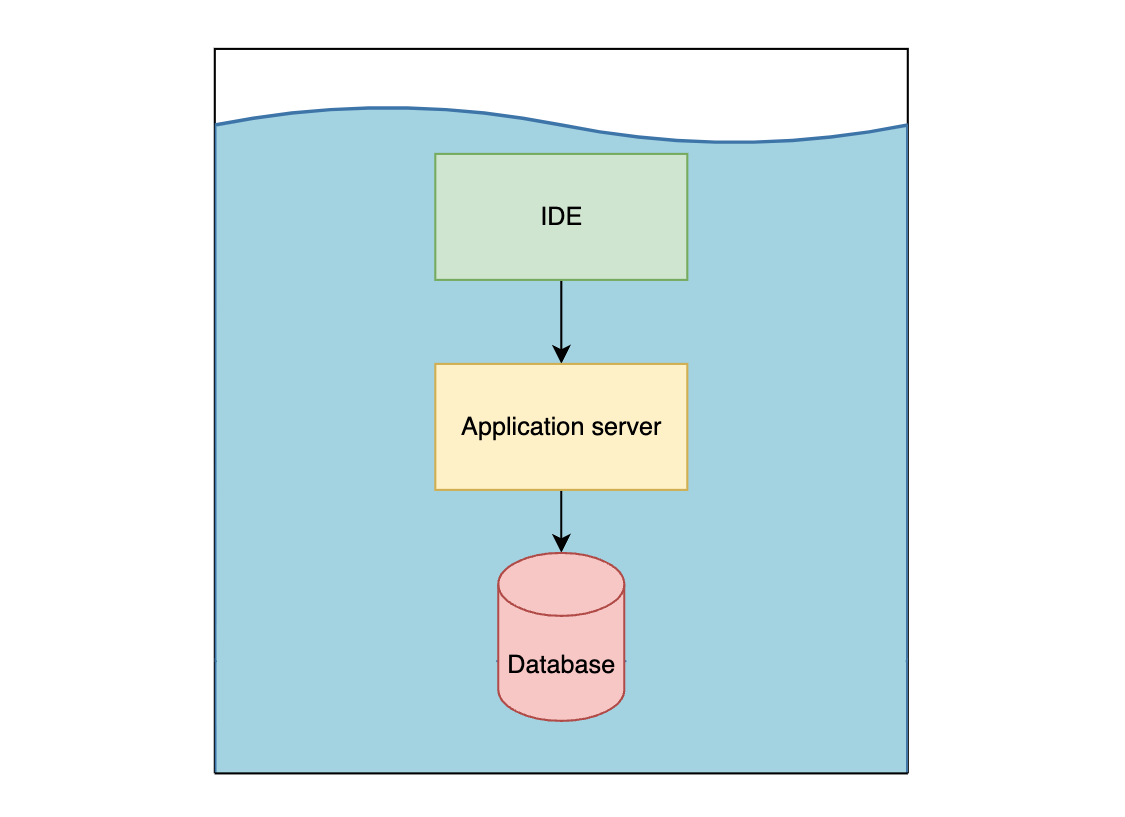

4. Go all-in

So if we draw the line just above the application server, we have a bunch of friction using our IDE/terminal to interact with the codebase / application server. Easy fix, let’s dockerise the IDE! That’s what dev containers are all about.

To use VS-Code as an example: you have a container which runs your development environment, including a VS-Code server, and your VS-Code window on your host machine simply connects to that container and defers all the work to the container. Your dev container lives inside docker, so now any scripts you run from within the dev container don’t need to mention docker, meaning you no longer need two sets of scripts. You can also return to the joys of having a single set of dependencies, so you only need to run npm install once and your IDE and application server will be in-sync.

And, you can now standardise the extensions used by the IDE, ensuring everything works properly across all dev machines. If a linter stops working, the problem will be within the dev container configuration, and upon fixing it, you can guarantee that it’s fixed for everyone.

What’s more, given that you’ve got pretty much everything in docker now, you can offload it to a cloud server and swap out your macbook pro for a potato hooked up to a monitor.

Wow. Inspirational.

But remember the tradeoff: we benefit from standardisation but we pay the price when any data needs to traverse the line. Consider the VS-Code client communicating with the dev container: if you stop docker desktop (cos it’s such a CPU hog and your fans are blasting so hard that your laptop is about to initiate takeoff) your VS-Code window will break and you’ll need to re-open the codebase on the host. This may sound like a non-issue but it is genuinely annoying, especially if you have unsaved scratchpad files sitting there which you want to refer back to.

Another example is the communication between your IDE and your host machine. Consider browser-based end-to-end tests: Playwright has a great integration with VS-Code that lets you click in the gutter to run your test in a browser. But when you’re using a dev container, Playwright’s going to complain that you don’t even have a display because as far as it’s concerned you’re inside a computer without a monitor. You can try to get around this with an X server but it’s going to look like crap, or you can try to get chrome running with a remote debugging port, and that too is hard (so hard that I actually have yet to successfully achieve it myself).

What to choose?

I wish I could give a clear answer on where to draw the line, but I don’t have enough experience with each option to weigh in with confidence. Each option sucks in its own special, unique way.

I’m keen to hear your thoughts: where do you draw the line? Or do you refute my framing and have a better way of thinking about it? Let me know!

Footnotes

-

Okay fine if you run linux natively alongside your main OS (ala WSL2) then you don’t incur the same performance penalty BUT you will still have some penalty with IO between the two OS’s e.g. when bind-mounting files. ↩

Shameless plug (which appears on every blog post, not just this one, so don't think that I'm opportunistically posting this specific post just for the sake of doing this plug): I recently quit my job to co-found Subble, a web app that helps you manage your company's SaaS software licences. Your company is almost certainly wasting time and money on shadow IT and unused/overprovisioned licences and Subble can fix that. Check it out at subble.com